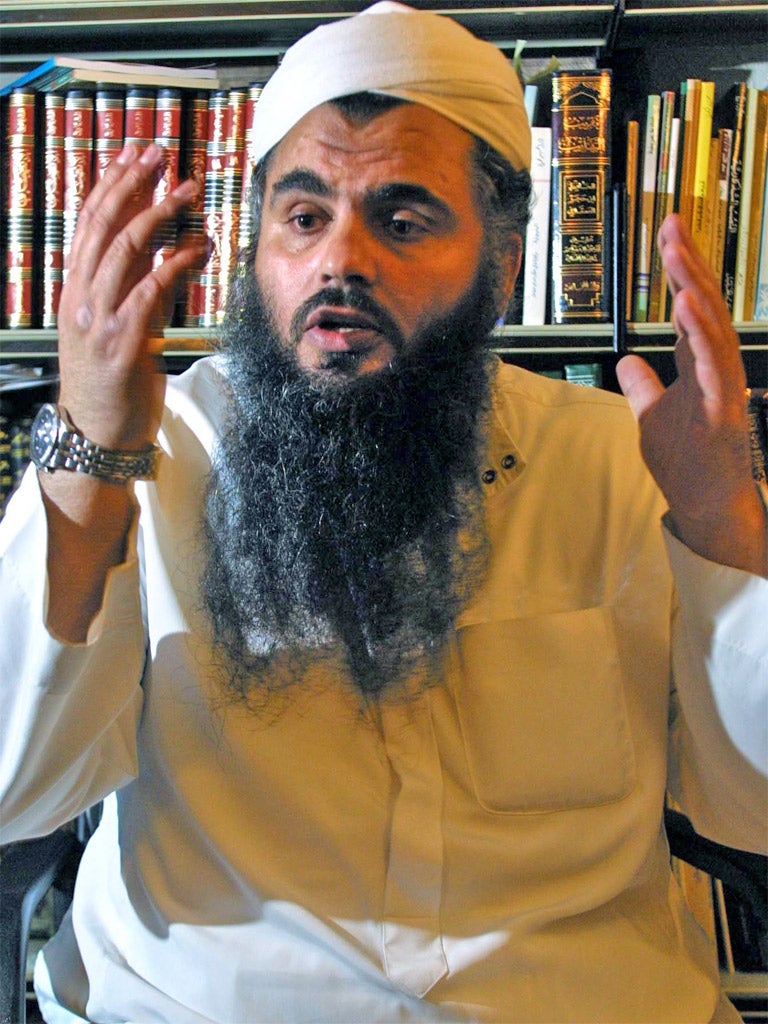

The case against Abu Qatada

He's been detained for almost a decade but never charged. So what exactly is it about the Islamist cleric that makes him 'a grave threat to national security'?

It was just 19 days before the Millennium that the Jordanian authorities began rounding up suspects. Two weeks earlier, the intelligence services had intercepted a message from known Islamists believed to be linked to al-Qa'ida, an organisation yet to carry out its most notorious and deadly attack.

The targets, part of a coordinated international assault on the Western celebrations to mark the date change, included Israeli, American and Christian sites within Jordan. In the end they were thwarted. At the trial it was alleged that a Jordanian living in London called Omar Mahmoud Mohammed Othman, now better known as Abu Qatada, had played a vital role in setting up the attacks.

Yesterday, the Home Secretary Theresa May told the House of Commons that a senior immigration judge's decision that Abu Qatada should be bailed was unacceptable. "The right place for a terrorist is a prison cell; the right place for a foreign terrorist is a foreign prison cell far away from Britain," she told MPs.

Ms May was speaking in the wake of a European Court for Human Rights decision last month that the 51-year-old cleric, who has been in prison in Britain for the best part of the past decade fighting extradition, could not be returned to Jordan because the authorities could not provide assurances that a trial there would not involve evidence gained through torture.

One of Abu Qatada's alleged conspirators, who was later sentenced to death, claimed the cleric had provided the plotters with money to buy a computer. It was also alleged he had encouraged them to carry out the attacks through his writings which had been discovered at the defendant's house.

Abu Qatada was already known to the Jordanian authorities. In 1999 he was found guilty (again in his absence) by a state security court of conspiring to cause explosions at the American School and the Jerusalem Hotel in Amman a year earlier. He was convicted on the evidence of one of his co-defendants, who claimed he had encouraged the cell to carry out the attacks and congratulated the group after they had done so.

The cleric was sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour for his role in the 1998 attack. For the second offence he was sentenced to 15 years in jail, again with hard labour. In both cases the defendants later claimed they had been tortured – allegations that were rejected by the Jordanian authorities.

Abu Qatada has lived in the UK since 1993, when he entered the country with his family on a forged United Arab Emirates passport. He was granted asylum nine months later, becoming a potent figure in the extremist intellectual community in London during the 1990s. He was imam at a mosque in north London, and preached across the capital where he built a strong following. In evidence which later emerged at one of his Special Immigration Appeals Commission hearings, it was claimed that in 1995 he issued a "fatwa" which appeared to justify the killing of "apostate" women and children in Algeria.

A 2005 Home Office report on him concluded: "He provides advice which gives religious legitimacy to those who wish to further the aims of extreme Islamism and to engage in terrorist attacks, including suicide bombings. A number of individuals arrested or detained in connection with terrorism have acknowledged his influence upon them."

In February 2001, he was arrested and questioned by anti-terrorism officers in connection with a German terror cell which plotted to blow up a Strasbourg Christmas market. All charges were later dropped because of insufficient evidence – but tapes of his sermons were discovered in a Hamburg flat used by the 9/11 hijackers, earning him the title of "spiritual guide" to ringleader Mohamed Atta.

After the introduction of new anti-terror legislation in the UK in the wake of 9/11, Abu Qatada, who had hitherto lived with his family in Acton, west London, disappeared. His absence and previous alleged contact with MI5 prompted speculation he had agreed to provide the British authorities with information on suspects in the war on terror. But in 2002 he was traced to a council house in south London where he was arrested and taken to Belmarsh Prison – setting in trail his long battle against deportation.

During this time, Abu Qatada was indicted by the Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzon along with several dozen other suspected militants. The court claimed the cleric had provided support and funds to al-Qa'ida militants in Europe, the Middle East and Afghanistan. Abu Qatada continues to deny any involvement with terrorism or ever meeting Osama bin Laden despite the repeated insistence of several home secretaries that he is a danger to the public.

Abu Qatada says he fears he will be tortured should he be returned to Jordan. And since his arrest in 2002, because of the security considerations surrounding his case, he has lived in a legal twilight world, explained Asim Qureshi, of UK-based human rights group CagePrisoners. "He has not been able to see the evidence against him neither has his lawyer. The only person representing him is a special advocate who is not allowed to speak to him or his solicitor. There you have the bizarre situation where someone is representing him who has never met him or his lawyer," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks