The DeLorean: How the Back to the Future car brought pride to a troubled Ulster

So modern that it had a starring role in Back to the Future, John DeLorean’s Belfast-made car showed another side to Troubles-era Ulster - nearly 40 years on, the gull-wing marvel remains a source of pride

The peace line – one of the metal-and-concrete barriers separating Belfast’s nationalist and unionist neighbourhoods – disappears into the foggy distance, and I ask Ken, my affable taxi driver, if he thinks they’ll ever be got rid of.

His almost comically aggressive “No!” is like a ton of bricks coming down around my inquiry. He’s that sick of tourists asking the same thing. I look out through the car window, puzzling at the murals and messages emblazoned on the barrier, and we move on. Belfast has a fraught relationship with roads and cars.

You can take these taxi tours out to the Falls Road and the Shankill Road, but the peace lines make it impossible to keep your bearings. Blocking roads has always been a political act here. During the Troubles, Republicans and Loyalists did it with makeshift barricades to protect their areas, and the British Army did it with their own fortifications.

Car bombs were a way of life, as well as death, and certain vehicles acquired a distinctiveness. The IRA drove Austin Marinas and Ford Escorts. When British soldiers took to the road, they did so in pug-nosed Saracen armoured personnel carriers and Land Rovers.

But in the midst of the Troubles it was a different kind of vehicle entirely that came to define Northern Ireland. It was neither a drab British marque nor a piece of alienating military hardware. Instead, it was something exotic, futuristic, fantastical and glamorous, speaking of a world a million miles from a province plunged into darkness by brutal sectarian violence. It was the DeLorean DMC-12 – a revolutionary US sports car. Nearly 40 years on from Ulster becoming the unlikeliest location for what would prove to be short-lived DeLorean production, the car is firing people’s imaginations all over again.

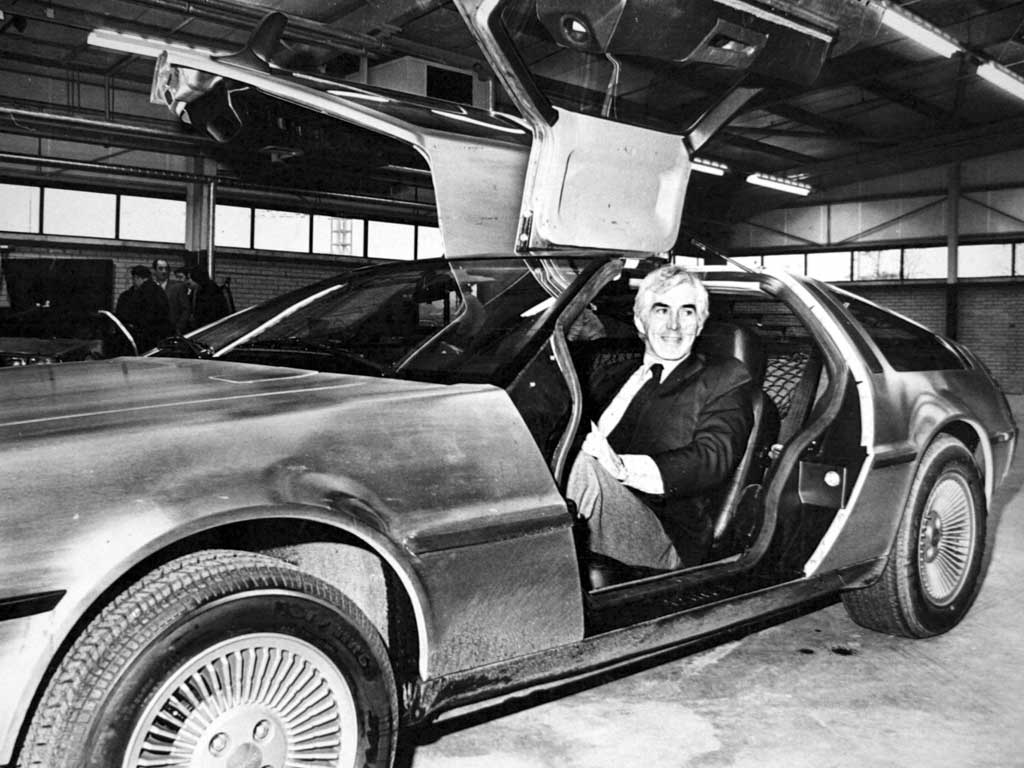

The creation of swaggering American auto icon John Zachary DeLorean, its unique styling by the Piedmontese design maestro Giorgetto Giugiaro, the DeLorean is one of the most recognisable cars ever made. Even people who are car-clueless know a DeLorean when those gull-wing doors pop open; when they eye that distinctive boxy profile.

I became fascinated by the DeLorean some years ago and soon discovered that I was not alone. But which soil did the dream emerge from? DeLorean built his factory in the Dunmurry area of Belfast, which stood – symbolically enough – on a bog between the Protestant Lisburn Road and the Catholic Twinbrook Estate. Twinbrook was the home of hunger striker Bobby Sands, who worked in the motor industry himself before he died in Long Kesh prison as the first DMC-12s arrived.

John DeLorean was from a city less cramped but no less segregated than Belfast. Detroit is wide open. You can (if you’ve got the legs for it) stroll through deserted plots, between community allotments and strip clubs, strip malls and dive bars. There’s segeregation, but it’s more subtle – there aren’t fences and walls like in Belfast – there are freeways and spaces, sky and emptiness. Right in Detroit’s bullseye is the gaudy, post-modern HQ of General Motors, the corporation that John DeLorean rose through the ranks of as a charismatic executive. He loved to party with Hollywood producers and TV stars, to bed models and actresses. He was a celebrity with the gift of the gab. And when he persuaded the British government in 46 days flat to stump up subsidies for his factory in Dunmurry, he finally got what he wanted: the chance to make his own car. The diggers moved in to start construction of the plant in October 1978, as The Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks” came out. Suddenly, not everything in Ulster came back to bombs.

These were strange times. The dominance of the American car industry, and of the fast-talkers who ran it and sold its products, is reminiscent of Mad Men. I’m reminded of Don’s escapes in his car; Joan’s horrifying night with the Jaguar dealer. As a character, DeLorean was as mysterious as any of the fictional rogues of Madison Avenue, but in Ulster in the late 1970s he inspired devotion.

By 1982, however, the company was in a hole. A perfect storm had taken its toll: poor sales, recession, a bleak American winter, lukewarm reviews – especially of the car’s under-powered engine. DeLorean and Margaret Thatcher’s new Tory government seemed at war. The plant needed cash. It wasn’t forthcoming and eventually everyone was laid off. The dream had died. In October 1982 the FBI carried out a sting operation on DeLorean, and the resulting video appeared to show him toasting a forthcoming drug deal. Did he take the bait because he wanted to save DMC? Or was it a set-up? DeLorean was acquitted of all charges two years later. But in Britain the whiff of impropriety wouldn’t go away. Money had vanished. DeLorean never returned for questioning.

Barrie Wills worked as DMC director of purchasing, director of supplies, director of product development. I ask him whether he thought DeLorean’s rags to riches to rags story is similar to the car’s? Wills, who ended up in 1982 with what he called “the somewhat dubious title of acting chief executive in receivership”, replies: “Very similar. But I would prefer to focus on the positives which Northern Ireland should celebrate and maybe even use as a tourist attraction, alongside the Titanic – as an example of the technical and operational achievements of Northern Irish workers.”

The truth is that the DeLorean renaissance is already under way. It’s inspiring films, music, books and art. The car still matters to people – especially in its home, Ulster.

Of course that’s in part due to the enduring popularity of the movie Back To The Future, which featured the DeLorean as a time machine. Back To The Future Part II imagined what the world would be like right here in 2015 – DeLoreans were still a part of it in the film, and they still are in the real-life 2015, too. In fact this stainless-steel car is as popular as ever. Of the 9,080 built at Dunmurry, 6,500 remain worldwide – 300 in Britain, hundreds in Japan, 20 in Norway, 20-odd in New Zealand.

It’s not just Robert Zemeckis and Steven Spielberg who were influenced by DeLorean’s car. Basque band DeLorean chose a name befitting their retro-futurist Balearic sound. And in 2008, the musician Gruff Rhys released a highly polished concept album about John DeLorean, called Stainless Style. When I reviewed it for the music website Drowned In Sound, I knew nothing about DeLorean’s life – but since that point he, and his car, have got under my skin.

Other people have felt it, too. “Much of my work is based on chasing up rumours and lost histories,” explains artist Sean Lynch from Venice, where he’s Ireland’s entry at this month’s Art Biennale. “I took a particular interest in DeLorean – my father ran a garage in Ireland for 25 years. I heard a rumour about the leftovers of the factory ending up at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and so began a search through the scrapyards of Ireland to try and verify this story.”

Lynch’s wanderlust ended up with an exhibition called DeLorean Progress Report, which impressed London’s art crowds last month. Lynch found the remains of the cars that had been dumped in the sea off Ireland and photographed them with lobsters poking out from their submerged chassis. Another artist, Cyril Hatt, also recently created a piece of DeLorean art. Along with 150 ex-employees, Hatt built a sculpture of a DMC-12 made from photographs stuck on metal. The finished product was the star of the recent Belfast Photo Festival. I spoke to Hatt from his home in Rodez, France, before the sculpture took shape, and he admitted: “It is exciting but I cannot forsee at all what the piece will look like, neither how we are going to deal with all the different processes.”

Many of those DMC line workers – and their colleagues from Lotus who also worked on it – gathered in Belfast earlier this year for a reunion. Barrie Wills, who’s publishing a memoir called John Z, the DeLorean & Me in October, helped to organise it.

“The reunion was the first ever. It celebrated the 35th anniversary of the first public showing in the spring of 1980 of the ‘Visioneering’ [prototype] car, manufactured as a joint exercise by DeLorean, Lotus and Visioneering personnel in Fraser, near Detroit.”

It wasn’t just workers who gathered in Belfast, it was fans of the car, too.

“I saw them on TV back in the 1970s. I thought, ‘That’s a damn good idea!’,” remembers 73 year-old Dave Howarth, owner of three DMC-12s and President of the British DeLorean Owners Club. “I was a plumbing and heating engineer back then and my hands were ripped to pieces with stainless steel. Well, maybe a car made of it was for me.”

Things got serious for Howarth. “I went to the Motor Show in 1981 and thought: ‘I’m gonna have one of these’. It cost £16,283 – twice the price of a Porsche! To me, they still look as modern as they did then.” Howarth’s cars had some famous owners. “One, John Taylor of Duran Duran owned. One of the others was owned by DeLorean’s brother-in-law. Howarrth and the other DeLorean owners will be packing their bags and converging on the Lotus factory at Hethel in Norfolk for a big owners’ event in August. I ask Howarth whether he thinks that DeLorean was guilty of fraud, of conspiracy to supply drugs. “No! He did what he said he would do.” Howarth is convinced that John was only trying to save the plant. Yet many of the car’s most ardent fans, and some ex-employees, forgive John’s sins. They see him as someone who wanted to create something unique, who supplied jobs to Northern Ireland when it needed them the most, and who fought against the cartel of American auto makers. Did the big companies have it in for John? In an eye-opening ATV documentary from 1981 directed by DA Pennebaker, John DeLorean is filmed telling a New Orleans talk radio host that it would take a big car company “seven or eight seconds” to finish him off – if they wanted to. John laughs. But was he joking?

The era when the DMC-12 was born feels so recent and yet, when you watch films such as the dealers’ presentation video on YouTube it looks a million miles away.

A shadier, stranger era.

When I was a child, I remember being taken to car showrooms when my parents were browsing. The showrooms seemed so wipe-clean. How did the cars even get inside? The dream of a car was so removed from its birth, from its reality. In 1973’s symphorophilia satire Crash, JG Ballard picked apart how these machines for moving us seemed to now menace us, to be greedy and strange (and enticing). Who was behind the wheel? And who was behind the political wheel? Secrets were everywhere. Social democracy was dying, utopian ideals were dead; Thatcher and Reagan came to power and only the market mattered. The age of the individual began. No-one trusted anything or anyone. The pages of Private Eye were awash with corruption and fraud. DeLorean seemed positively patrician in comparison – even though he was in and out of court until his death 10 years ago.

The contrast between chilly, crippled Belfast and the hazy, dreamy Santa Barbara sunsets that the car drives through in that 1970s dealers’ video couldn’t be starker. But the continued existence of the car, and of the artists, employees and aficionados who adore its quirky story – and that of its founding father – mean that this odd connection between Belfast and the American freeway will always be remembered.

Sean Lynch – DeLorean Progress Report, Ronchini Gallery, London, runs until 27 June; ronchinigallery.com

DeLorean Print Project, Belfast Photo Festival, runs until 30 June, Belfast; belfastphotofestival.com

DeLorean Owners Club Festival, 14-16 Aug, Lotus Factory, Hethel, Norfolk; deloreans.co.uk/lotus-2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments