Vellum: UK's last producer of calf-skin parchment fights on after losing Parliament's business

As of next month, archive copies of Acts of Parliament will cease to be printed on vellum, saving £80,000 in costs

In the company’s original office, with its 1855 safe, overlooked by a photograph of the firm’s founding father, the general manager of parchment and vellum makers William Cowley receives a steady stream of phone calls from sympathisers and customers.

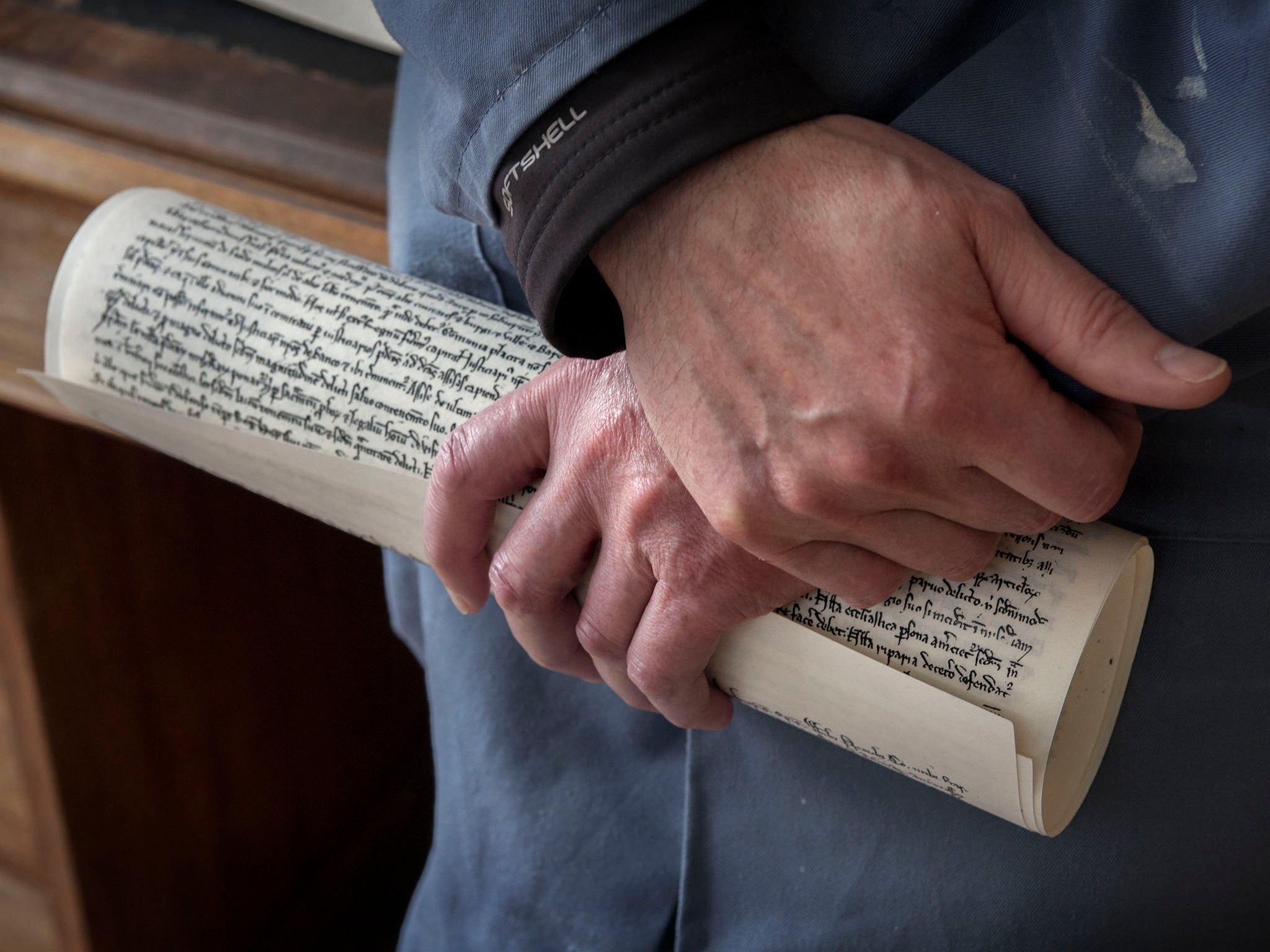

Paul Wright tells them how parchment and vellum are “the earliest writing materials, in use since man stepped out of a cave, wrapped some skins round a few sticks to make a tepee, and started scribbling on his tent walls”. He added: “All of humankind’s history is on parchment and vellum. Magna Carta was written on parchment. The Dead Sea Scrolls: parchment, in 435BC.”

Today, he says, William Cowley, based in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire, may be the only company in the world making “proper” vellum in the proper way – “without any harsh chemicals, by hand and hard, pigging work”.

Time was, though, when every law worth having was written on vellum, when vellum meant power, when it was “so sacred, so prized that the finest vellum makers would be abducted, stuck in a dungeon and forced to make vellum, so whichever side it was, royal or religious, could make their own laws”. No longer.

As of next month, archive copies of UK Acts of Parliament will cease to be printed on vellum. At the urging of members of the House of Lords, which pays for the printing, the Commons Administration Committee has agreed that once the present contract expires, Parliament should switch to something Mr Wright regards as a vastly inferior modern (14th-century) Chinese import: paper.

To save an alleged £80,000 on printing costs, Parliament is ditching a tradition that first decreed that Acts should be handwritten “in a peculiar strong black hand” on goatskin parchment and then, starting with the Inland Revenue Board Act 1849, printed on calfskin vellum.

How to make Vellum

Vellum makers first “read the skin”, examining the calfskin to determine exactly how to treat it.

The skin is then “rotted down’. Once, this involved a “walker” pressing it into a mixture of water, urine and dog muck with his feet.

Today Mr Wright and his team use a vat containing lime and secret mixture of natural ingredients concocted by the company’s founder, William Cowley.

Then comes “scudding”, scraping hair from the skin. Finally, the skin is stretched on a frame and imperfections like dark skin are scraped away. William Cowley employees use a crescent-shaped knife called a “lunar”, or “lunarium” – ancient vellum makers used flints.

Mr Wright, 50, is indignant. The battle for British vellum, he reveals, is just beginning. “This isn’t finished. There are MPs, bookbinders, artists, calligraphers – hundreds of people – who are not happy about this. And not just in the UK. There’s not a nation in the world where I don’t have a contact. This will go global.”

The fight, he says, will not be out of concern for his company. As the ringing phone testifies, he and his team have plenty of customers – from orchestras wanting vellum drumskins to foreign governments.

They produce thousands of pages of vellum every year. Only a couple of hundred are for Parliament. For “Paul of William Cowley”, the loss of that contract is “nothing”. For Paul, “the man, the taxpayer”, it is everything. Traditions matter here. The company hasn’t moved since William Cowley started making vellum beside the River Ousel in 1850. Mr Wright was taught the art of vellum making by Cowley’s great-great-grandson, Wim Visscher.

He feels proud that Julia Kainth, Cowley’s great-great-great-granddaughter is working here, keeping it a family business. He is dumbfounded by the vellum decision.

“How,” he demands, “can a handful of MPs and lords decide to throw out our history, the material that has documented everything, since we stepped out of the cave? Without it even being decided by a vote of the whole House of Commons?”

The anti-vellum advocates say that, if stored properly, archival paper can last for 500 years. Mr Wright disagrees. “You can roll vellum up and leave it on a shelf – or in a cave – for 5,000 years. But you won’t find any paper manufacturer who will guarantee longer than 250 years. That takes us back to about 1750, and the rest of history we can kiss goodbye.

“It’s like we’re deciding to write our most momentous Acts on the back of a fag packet. For future generations, where will be the history we can touch.”

As for those costs cited by vellum’s opponents, Mr Wright unrolls a seemingly flawless replica Magna Carta, and points to his standard Epson Stylus printer. “I scanned and printed it on that.”

When confronted by the claim that the Lords pay £103,000 a year for the manufacture of vellum, he says: “They must have very expensive printers, because on average, they pay us £46,000 a year for vellum.” Once you consider the price of archive paper, says Mr Wright, the true savings would be more like £26,000. “Is that the price we put on having a documented record of our history?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments