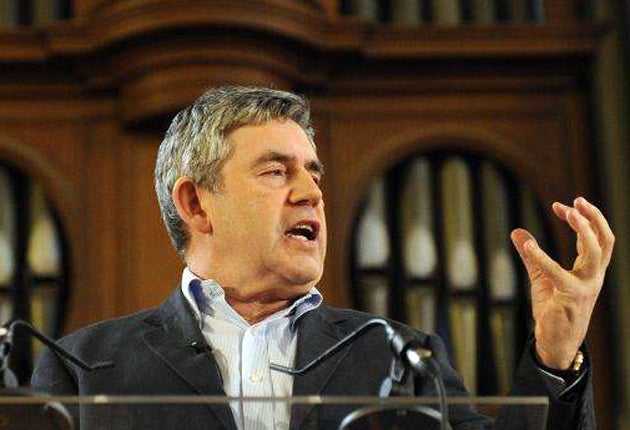

'Psychologically flawed? That doesn't come close'

In these exclusive extracts from the explosive memoirs of former spin doctor Lance Price, Gordon Brown's draconian rule at No 10 is laid bare

Standing on the front step of Downing Street for the first time as Prime Minister, Gordon Brown promised to lead "a new Government with new priorities". Before turning and disappearing inside he declared: "Now let the work of change begin."

The message he wanted to convey was unambiguous. This Prime Minister was going to do things very differently to his predecessor and changing the way Downing Street dealt with the press was a high priority. Even before the expenses scandal of 2009, Brown knew that the public's faith in politics generally, and in New Labour in particular, was at a low ebb.

He believed Tony Blair's use of the media was a contributory factor, but his attempts to change the culture were very quickly disappointed.

According to Damian McBride, who was the nearest thing Brown had to an Alastair Campbell figure, "it was a noble experiment but probably doomed to failure in the age we live in".

Others who have worked inside No 10 at a senior level since 2007 and have seen the media operation at work are less charitable. They are unable to give their views on-the-record while Brown is still Prime Minister, but they say he and his closest advisers must take responsibility themselves for seeing the reputation of 10 Downing Street sink still further so quickly.

Brown entered Downing Street with the best intentions sincerely held. Above all he wanted to rebuild the public's trust through an open and honest dialogue about the problems facing Britain and what he hoped to do to address them. Many correspondents who had worked at Westminster over the previous decade were doubtful. In their experience Brown had been no more straightforward in his dealings with the media than Tony Blair, indeed in many ways less so.

Brown wanted to put policy first, with presentation a distant second. His promise was summarised by the media as "an end to spin" although he never used those words. One of those who joined Brown in No 10 six weeks later now believes there was less to the pledge than at first appeared: "No more spin was the new spin. Almost everything they did in the initial phase was simply about delineating themselves from what Blair and Campbell had done."

One adviser to the governments of both Blair and Brown described the new administration's media-management plan as "all tactics and no strategy, scarily so".

If Brown saw something he didn't like he would rush to the press office and demand that it be corrected or that a response be issued immediately.

His personal intervention helped Downing Street look very much in control when the first crises hit, including terrorist attacks in Glasgow and London, summer flooding in the north of England, and an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Surrey.

At times, however, he seemed to want to direct every minute detail of policy and presentation himself. One person who witnessed it said: "He would come racing round and stand over people saying, 'You've got to get this bulletin changed,' or 'We've got to get this corrected for six o'clock. I've got to do a clip.' On one occasion during foot and mouth it was about a cracked pipe on a farm and I thought to myself, that's probably a bit below the job of a junior minister at DEFRA [Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs]." Another recalled him "storming into the press office dictating a press release in response to something he'd seen on the television, except he'd misread it. It was embarrassing."

Brown likes to start the day with an early briefing over the phone on what the media are reporting. This is followed by a wider conference call with his other key advisers at 7.30. He is not an avid reader of newspapers, although he will look at the front pages and the main political stories. His preference is for regular verbal updates during the day. "He will regularly ask, 'What's going on? Everything under control?' " When he believes a story is running out of control or that – the worst sin of all – the press office has been caught unawares, he can react with extraordinary flashes of anger. Stories of mobile phones hurled across the room in fury regularly appear in the press, although it rarely gets to that stage. Shouting at staff, jabbing an angry finger, throwing down papers, even kicking the furniture are far more common.

His behaviour towards relatively junior members of staff can be "unforgivable" according to one person who has witnessed it. "It isn't a very nice place for people to work. However bad it sometimes looks from the outside, it's far, far worse from the inside. And the atmosphere is very much set by him." Those in the press office more used to dealing with the daily onslaught of unpredictable news put it down to Brown's 10 years in the Treasury, where events could be carefully planned and the phone never rang in the middle of the night with another crisis to be handled.

It is Brown's misfortune that he is forever being assessed in the light of the observation that he is "psychologically flawed". Those who have witnessed his behaviour refer back to it constantly without being prompted. "It doesn't come close," said one. Another said Brown was always looking for somebody else to blame when things went wrong. "It's this self-pity thing. There's a pathetic side to him that is really unbecoming." A third said the problems have got no better with time, concluding: "He is psychologically and emotionally incapable of leadership of any kind."

McBride, however, thinks that those who know Brown less well misunderstand his moods. "In the entire time I've been working with him I've never seen him throw anything. I've seen him do lots of other things.

"I've seen him shout and swear, but that is a superficial thing, to release a bit of frustration. The times when he's really angry are not when he shouts but when he's quiet. Sometimes civil servants come out of meetings and think, 'Oh that went OK,' because they had been expecting him to explode when actually he'd be very quiet. But it's then that he's really angry."

Having concluded the polls were too volatile, Brown decided against an election in the autumn of 2007. Privately some of his closest advisers said he had "bottled it". Having anticipated an election Downing Street was left with a vacuum as the summer of confidence turned into an autumn of recriminations. Brown's loss of political authority prompted exactly the kind of stories about Government divisions that Downing Street had been determined to avoid.

"There was no exit strategy when the election was called off," said one civil servant. "They were left with nothing. The autumn was a shambles." Another put it down to a lack of strategic vision that left the press office unsure what they were selling. "What was missing was an overall narrative – what the big picture was. That has to come from the boss."

Little more than six months after his succession, Brown's insistence that No 10 should speak only with one voice was flagrantly ignored. A new duopoly of power was created at the top of the No 10 administrative structure with the arrival of Stephen Carter [chief executive of City PR firm Brunswick] as head of strategy and "principal adviser" to work alongside Jeremy Heywood [the Downing Street Permanent Secretary]. While Carter was a talented and confident administrator, he was outgunned politically. When the current director of communications Simon Lewis was appointed, figures in Whitehall feared Brown had again appointed "a smooth top-class PR man" rather than the political heavyweight the communications team still lacked.

The Prime Minister faced a familiar dilemma. If the Downing Street press office is too political it runs a far greater risk of generating controversy. If it is not political enough, its ability to communicate the Prime Minister's objectives will be hampered.

Gordon Brown faced the few months before his fate would be decided at the ballot box with trepidation. Mastery of the media, once New Labour's weapon, was in other hands. Power no longer lay where it had been thought to lie. No Prime Minister in the years to come would need to concern him or herself with flattering and placating the owners of newspapers to anything like the degree their predecessors had. Nor could they expect the luxury of exercising as much untrammelled power as previous incumbents. The system Brown had grown up in and learned to dominate had changed dramatically and was changing still.

He had come to the job he had coveted just when his own political skills were becoming redundant and his discomfort was painful to observe. Yet however inglorious his premiership may have looked, from its many tribulations has emerged the possibility of a healthier relationship between the government and the governed and, perhaps, between Downing Street and the media. Both sides have had to learn a little humility and to look afresh at how they operate. How far-reaching the change will be has still to become clear, but business as usual is no longer an option.

Extracted from Where Power Lies. Prime Ministers v The Media, by Lance Price, published by Simon and Schuster (£20)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments