Gaddafi clings to Tripoli – but for how long?

A special report from inside the embattled Libyan capital

Muammar Gaddafi's opponents unfurl a rebel flag from a motorway overpass in the dark and speed away. On the outskirts of the capital, masked protesters denounce the Libyan leader, then quickly disband. The pop of gunfire is heard almost every evening, some of it, according to dissidents, from sneak attacks on army checkpoints.

Furtive resistance is the best those seeking Gaddafi's removal can muster, under the heavy weight of fear in the most important stronghold of his rule. But the fact that such small-scale actions are taking place at all is a sign that activists are still trying to bring the rebellion to the capital, even after Gaddafi's forces gunned down demonstrators two months ago. If confirmed, the reports of sporadic shooting at security posts could mark a significant shift away from peaceful protest, signalling the desperation of regime opponents in Tripoli.

At the same time, major disruptions in daily life – a result of international sanctions and the exodus of hundreds of thousands of foreign workers – will likely erode support for the regime. The price of cigarettes has doubled. Drivers wait hours to fill up petrol tanks, with queues of cars snaking around city blocks. Large crowds form outside bakeries that can no longer keep up with demand.

Tripoli is the wild card in the deadlock that has gripped Libya's two-month-old rebellion. Rebels control roughly the eastern half of the country, Gaddafi's regime most of the west. International air strikes have prevented Gaddafi's forces from taking back rebel territory, but the opposition has been unable to advance on the west to oust the Libyan leader. An uprising in the capital with a million people could dramatically change that equation, which is why the government has clamped down so hard. The internet has been disrupted, and dissidents say people avoid speaking openly, even to friends. There's also little contact with the rebel movement in the east, a rebel spokesman said.

Some believe the wall of fear protecting Gaddafi may soon be coming down.

"I think that we are reaching a tipping point," said Peter Bouckaert, a Libya expert and director of emergency response at Human Rights Watch. "From our discussions with people in many of the western cities, they are waiting for the moment to join the protests."

Government officials claim Tripoli is solidly behind Gaddafi, saying the regime has released hundreds of thousands of rifles into the streets to arm ordinary people for a home front. And some Tripoli residents told reporters they blame the West for their troubles, not their leader of 42 years. "We are not isolated; it is not Gaddafi against the nation," said Moussa Ibrahim, a government spokesman. "How is it that you would arm a nation that would fight against you?"

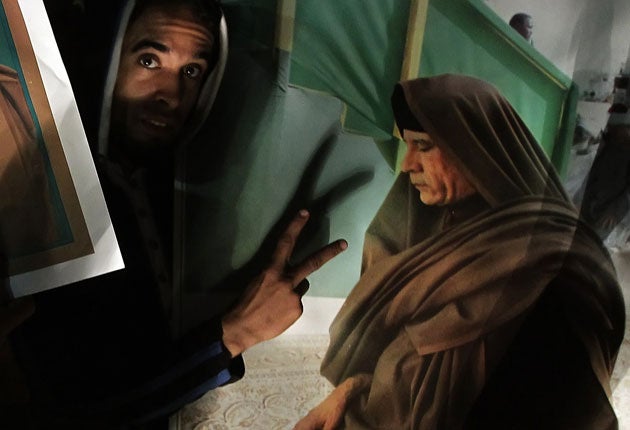

While huge paintings and photographs of Gaddafi cover billboards, hotel lobbies and government offices, the "brother leader", as Libyans call him, has appeared in public only a few times since the start of the fighting. State TV showed him poking through the sunroof of a 4x4 and pumping his fists as supporters ran alongside last week. Journalists, especially in Tripoli, can travel only with government escorts, who stage shows of support for Gaddafi. Regime supporters, usually sporting green scarves or headbands and chanting "Only God, Muammar and Libya", show up in remote locations precisely when reporters arrive.

When talking in the company of minders, Tripoli residents usually say everything is "miyeh-miyeh", or perfect. But out of earshot of the escorts, people speaking on condition of anonymity, present a different picture. In the city's old bazaar, a 40-year-old gold salesman said he believes support for Gaddafi is dwindling. The owner of another gold shop, standing next to an empty display counter, said he keeps most of his merchandise at home because he is concerned about deteriorating security.

The 38-year-old owner of a souvenir shop said business has dropped by 80 per cent. Life under Gaddafi wasn't too bad, he said, but people turned against the leader after his troops started killing protesters. He was at a protest outside a mosque last month when police opened fire. He is now too scared to demonstrate.

In another area of Tripoli, a 22-year-old woman approached a reporter in a clothing shop. "Don't believe what these people say," the young woman said in English, after overhearing two middle-aged customers say in Arabic that life in Tripoli was normal. The young woman, a bride-to-be, walked away from the other shoppers and pretended to be searching a rack of nightgowns. Speaking in English, she said her brother has been missing since police opened fire on protesters last week. Clearly fearful, she then walked back to the front and said loudly in Arabic that the people are behind Gaddafi.

The signs of a clampdown are everywhere, particularly on Fridays, now a day of demonstrations in the Arab world. On a recent Friday, Tripoli was deserted.

"There were armed checkpoints every 200m, and not a soul on the street," wrote a physician turned activist in an email to journalists. Along the edges of a large roundabout in the Furnag district, off-road vehicles had been arranged in a circle facing outwards. Kalashnikov assault rifles pointed out of every window, he wrote, and teenagers with green flags, bats and knives stood inside the circle.

Policemen in cars cruised the area taunting dissidents over loudspeakers. "Where are you rats? Where are you rats? Why are you not coming out?" wrote the physician. "In the face of such overt intimidation and aggression, what scope is there left for anyone to raise a banner peacefully demanding freedom and to march on the streets of our city?"

Other regime opponents, reached by phone, said strangers have started showing up in local mosques, presumably undercover agents. One man said he and his friends went straight home from the mosque last Friday after seeing a vehicle mounted with an anti-aircraft gun parked nearby.

In mid-February, when the region's wave of revolt reached Libya, thousands took to the streets in Tripoli, waving rebel tricolour flags. But in subsequent days, gunmen in 4x4s descended on homes at night to drag away suspected protesters, identified from security videos. Other militiamen searched hospitals to arrest wounded people. Since then, there have been no more mass protests, but dissidents say acts of resistance continue, such as days of fasting or tying the rebel flag to cats and dogs. A video posted by regime opponents shows a rebel flag – with the date 19 April and the words "Libya is Free. Tripoli" – hanging from a central motorway overpass earlier this week. Activists said the flag stayed up for 15 minutes. Another video showed a dozen masked demonstrators reading an anti-Gaddafi statement.

Rarely a night passes without heavy gunfire at local checkpoints from roving bands of protesters, said a Libyan journalist in Tripoli. The physician said security forces now avoid certain areas for fear of being ambushed. "The attacks are so frequent and widespread that it suggests the groups are numerous and well equipped," he said. Bursts of gunfire are heard frequently from a hotel where foreign journalists are based, sometimes accompanied by the honking of car horns. Mr Ibrahim, the government spokesman, said all the shooting is celebratory, from Gaddafi supporters firing into the air. Government officials and regime opponents say Tripoli is flooded with weapons. They are now largely in the hands of Gaddafi supporters, but could be turned against the government one day or fall into the hands of dissidents.

Daily life is strained. At a bakery in Tripoli's Bu Slim district, a Gaddafi stronghold, two dozen people waited for bread. The Egyptian workers have left and their Libyan replacements aren't up to speed, said Mohammed Abu Qraa, 25, one of the new workers. "Our problem is with Nato, not with Gaddafi," said shopper Mabrouka Daheel, a mother of eight. However, Ashur Shamis, a Libyan exile in London, believes the growing hardships will eat away at what remains of support for Gaddafi. "People are getting fed up and agitated," he said. "It is up and down all the time, but one day it is going to explode."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments