Jimmy Morales: How the comedian became president of Guatemala

Heard the one about Guatemala's president? Don't laugh – because, inspired by other comics-turned-politicians, tacky funnyman Jimmy Morales takes office tomorrow

Lewd, crude and inappropriate are just three adjectives that could be used to describe the wit of Jimmy Morales, Guatemala's most famous television comedian.

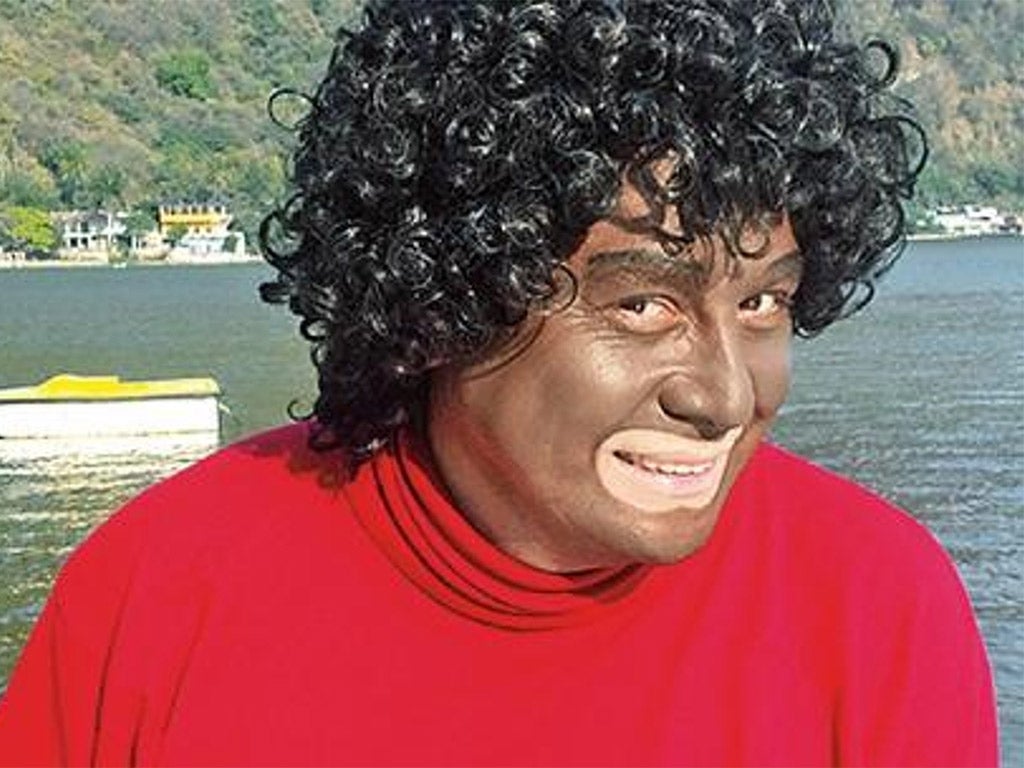

For nearly 15 years, Morales, along with his older brother, Sammy, starred in the weekly sketch show Moralejas ("Morals" in Spanish). Clips – which can be seen on YouTube – show Morales in various zany get-ups. More often than not as a country bumpkin, and on more than one unfortunate occasion in blackface.

If there is any political import to Moralejas, it's at a stretch subliminal; nay, non-existent. To use a UK comparison, more Keith Lemon than, say, Stewart Lee.

Yet, tomorrow, Morales – who, in 2011, changed his surname by deed poll from Cabrera – will be inaugurated as the President of Guatemala, having swept to power in October on the back of an impressive election campaign.

Even in the predictably unpredictable world of Guatemalan politics, Morales's ascent has been extraordinary; all the more so, given that he only put himself forward for the top job in April.

When his opponent and predecessor Otto Perez Molina was jailed in September amid the country's latest corruption scandal, Morales seized his opportunity, successfully tapping into public sentiment by positioning himself as the embodiment of anti-venality. The art of his campaign was in its simplicity, rather than any highfalutin' policies (his centre-right National Convergence Front party's campaign manifesto came to only six pages).

"Morales has an outstanding ability to empathise with voters' concerns and aspirations," says Hugo Novales, a political analyst at the Guatemalan think-tank Asies. "His support does not come from policy proposals – he explicitly proclaimed that he does not have a programme – but on a direct, emotional relationship with voters."

But what is it about comedians beating the political path these days?

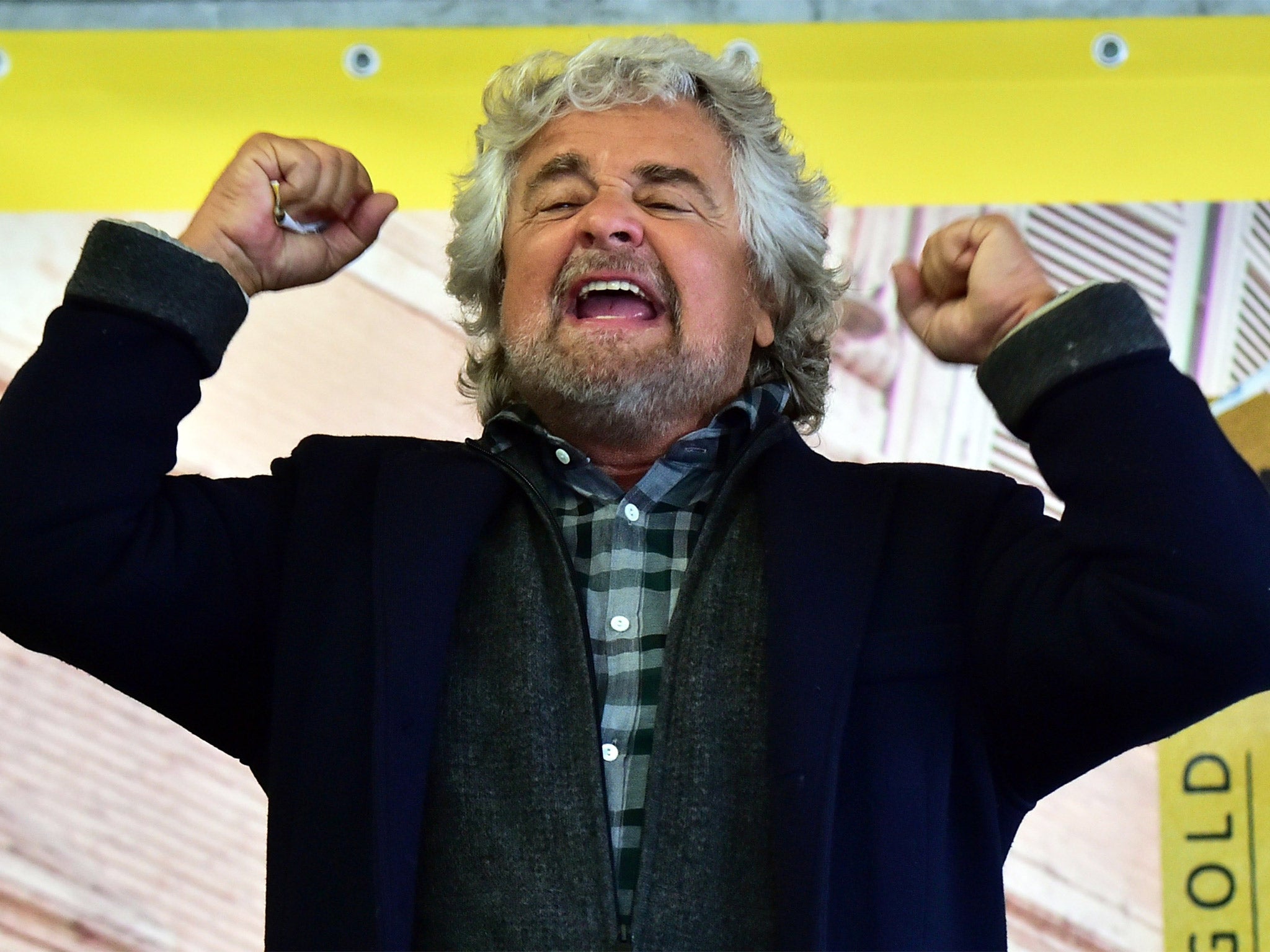

Morales's rise recalls that of Beppe Grillo, whose Five Star Movement came out firing in Italy's 2013 general election as the fiery, unadulterated – and somewhat dishevelled – face of anti-corruption. One in four Italians is now said to back the protest party.

Likewise, in 2010 the Icelandic comic Jon Gnarr became the Mayor of Reykjavik, riding on a wave of antipathy towards politicians who were blamed for the financial crisis.

From the outset of his campaign – initially launched as a satirical stunt on his television show – Gnarr positioned himself on the planks of "honesty and integrity, empathy, non-violent communication and fun", expecting little chance of victory.

And perhaps here lies the reason for his success – as well as Morales's. Counter to the well-oiled, pat, modern-day politicians, comedians are at ease with their own voices and inclined to self-deprecation and absurdity, but able to rely on their wits – for want of a better word.

Subversion is also key to this. While the very notion of having to stray off-message is sheer anathema for politicians, comedians often revel in sedition. Closer to home, this was no better exemplified than in the run-up to last year's general election, during which Russell Brand developed an uncanny knack for fomenting political debate, if at times misguided.

Even Al Murray's Pub Landlord character – whose FUKP didn't "claim to have all the answers, or indeed, any of them" – emerged to become Nigel Farage's highest-profile rival in South Thanet.

But maybe politics and comedy aren't such weird bedfellows as one might think, as Jo Silvester, a professor of psychology at City University's Cass Business School, explains.

"Comedians and politicians actually share an interest and skill in communication, rhetoric and engaging an audience," she says. "Of course, this isn't all it takes to be successful in politics, but there are likely to be shared qualities, such as emotional intelligence, too. However, that doesn't mean that comedians will necessarily be successful as politicians."

In a recent BBC interview, the comedian and prominent Labour campaigner Eddie Izzard – who has said he hopes to run for London mayor in 2020 – predicted more comedians will go into politics, "because it's a very analytical thing".

In the past, Izzard has often cited Al Franken, the Saturday Night Live performer turned Democratic Senator, as an example of how the cognitive skills associated with comedy can be transmuted into the political arena.

Jon Krosnick, a professor of political science at Stanford University, agrees.

"Although it's not true for all comedians, many tell jokes that lead their audiences to say, 'Clever insight! That's a fresh way to look at things!'" he explains. "In other words, jokes are often funny if they say something to people that they hadn't thought of before – showing them a different way to look at phenomena with which they have plenty of experience and that resonates as true and clever.

"All of those are qualities attached with being thoughtful, empathic and caring about others. That's what voters want to see in their politicians."

And maybe a sense of humour.

Profile of a president

Jimmy Morales' campaign slogan was "neither corrupt, nor a thief", which doesn't exactly instil confidence. The comedian-turned-politician is best known for his slapstick comedy show Moralejas (Morals), which ran for 14 years. In it, Jimmy and his brother Sammy played various roles, including bumbling cowboys Nito and Neto. In one rather prophetic episode, Neto (played by Jimmy) accidentally runs for president of Guatemala and wins.

In his most controversial skit, Morales wore blackface and a prosthetic bottom to play a character known as Black Pitaya, who spoke in a baby voice and told self-effacing gags.Morales has since defended himself against accusations of racism, claiming that Black Pitaya – who even appeared on a line of shampoos – was loved by Guatemala's black Garifuna and indigenous Mayan communities.

Morales once cited Charlie Chaplin's 1940 satirical film The Great Dictator, which mocks Adolf Hitler, as his inspiration, saying: "There's no other film that has such strong content – and it was done with humour."

It's no surprise, then, that the comedian has tried to include comedy in his campaign. Morales regularly quips with his supporters, starting rallying speeches with showman's cries of: "How're you doing, Guatemala?" He even shoehorns funnies into his addresses, including a joke-parable about a womaniser who tells one of his lovers about all the hardships he'd suffer just to spend the night with her. When the woman asks if he'll come over that night, he replies: "If it doesn't rain." Boom boom.

Morales' sketches might be puerile, but his policies are bordering on ridiculous. One of his more far-fetched ideas is to tag teachers with GPS devices to ensure they turn up to work, while another is to give each Guatemalan child a smartphone – presumably so they can watch re-runs of Moralejas on YouTube.

Chloe Hamilton

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments