China and Japan work towards resolving an enmity that stretches back centuries

World View

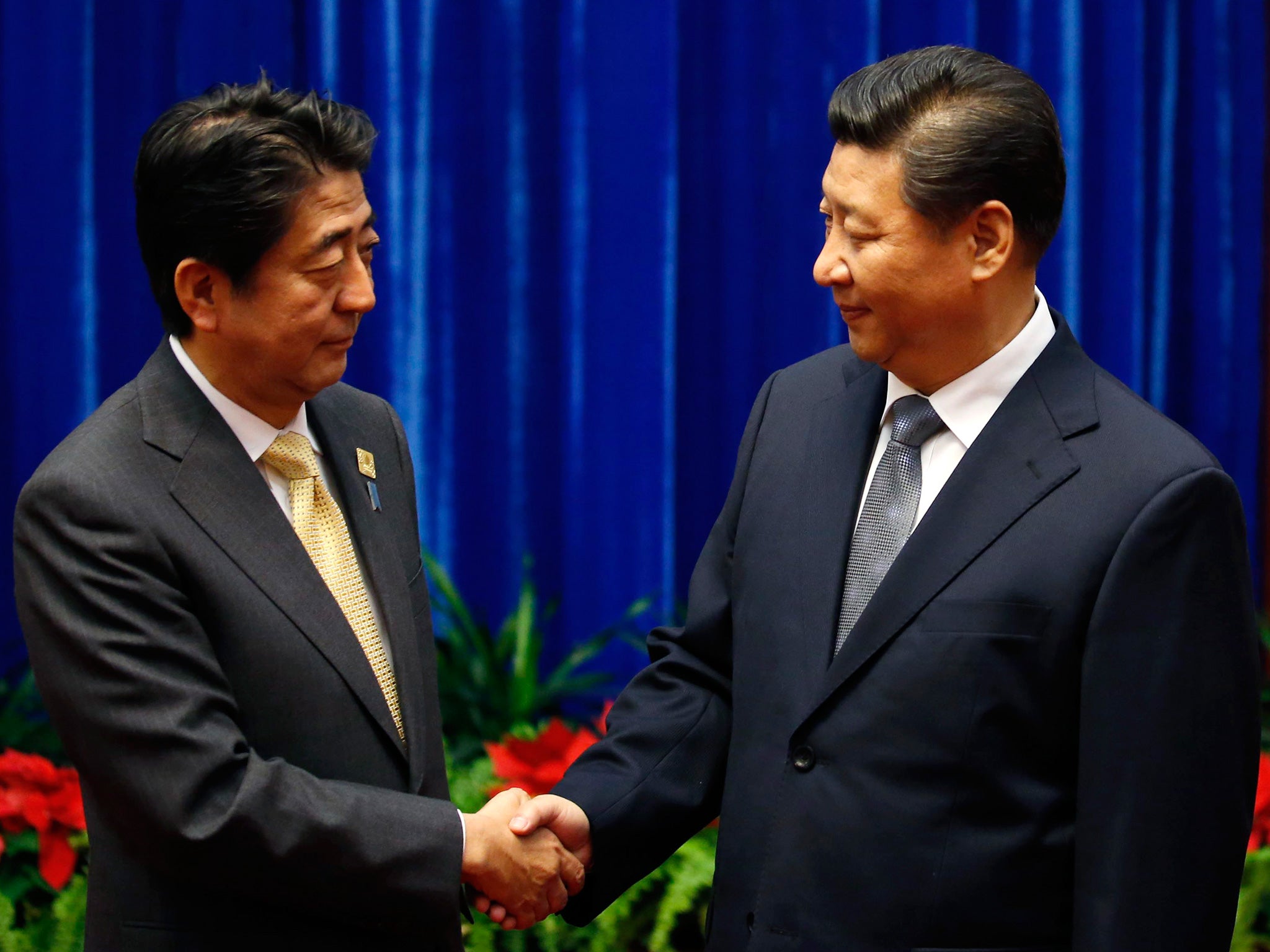

Four months ago they exchanged a strikingly awkward handshake. And today President Xi Jinping of China and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, despite their differences, appear to be edging towards peaceful co-existence – if they can find a way to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War without setting off another round of provocations.

The immediate issue between Asia’s economic giants is a cluster of rocks and uninhabited islands in the East China Sea which Japan calls “Senkaku” and China calls “Diaoyu”. Japan has claimed them since its first burst of maritime expansion at the end of the 19th century.

China, embroiled in what Chinese call their “century of humiliation”, was in no position to protest, and even today might have had no interest in doing so had not underwater oil been detected nearby.

The two powers have been sparring dangerously over the islands for the past couple of years, risking a military incident which could snowball into something far more serious.

So it was welcome news that this week they held their first bilateral meetings on security since 2011, to thrash out the details of establishing a telephone hotline for use in such an emergency.

The talks have gone with painful slowness and have yet to reach a conclusion, but both sides recognise the importance of cooling the temperature. But these apparently worthless islands are merely the visible projection of hatreds and divergences that go back many hundreds of years.

The rawest and most recent of these was the invasion of China by Japan in the 1930s and the massacres that ensued, especially that of the city of Nanking.

It was a brutal assault on Chinese sovereignty on the pattern of many such assaults by European colonial powers in the preceding century – but the fact that this one came from an Asiatic power, a tiddler in size compared to China, made it all the more bitter for the Chinese to stomach.

Historically and culturally the two countries are as closely intertwined as England and France. Practically everything one identifies as Japanese had its origins on the Chinese mainland, from rice cultivation to Buddhism, from the written language to the Confucian code.

But while the distance from Dover to Calais is barely 50 miles, from the Japanese to the Chinese coast – say from Fukuoka to Shanghai – is more than 10 times as far. Japan was therefore a much more formidable country to invade than England, and after the destruction of Kublai Khan’s fleets and armies in the 13th century, ultimately by the typhoon which the Japanese called kamikaze, “divine wind”, no further efforts were made until General MacArthur showed up in 1945.

Throughout its history England has played a vital role in European power politics – being too close to the Continent to do otherwise.

Japan, by contrast, was far enough away to have the luxury of true insularity, and indulged it to the full. Spared the threat of invasion, it shut up shop and turned inwards for centuries. And China, which refused to contemplate a relationship which was not one of respectful tribute, was happy to forget about its only real East Asian rival.

Over the centuries of mutual indifference and disengagement, the two nations evolved in very different ways. Yet the traumas of the 20th century left them with similar scars, similar complexes.

The waves of invasion and colonisation have left China determined to bury the humiliations of the past, to punch according to its weight and fulfill its manifest destiny in its own backyard.

And Japan, pulverised by US air power in the last year of the Second World War, with practically all its cities destroyed, then occupied and ruled by the Allies for the first years of peace, carries a comparable burden of humiliation and resentment – a burden which Mr Abe, a hard-line conservative and considered a revisionist by China, is as determined as President Xi to dispose of, and in the process restore the nation’s tarnished honour.

Motivated by parallel patriotic urges, it is not surprising that these chalk-and-cheese neighbours found themselves on a collision course once China began flexing its muscles. And the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War on 15 August gives both of them ample opportunity to provoke and antagonise each other all over again; or alternatively, to turn over a new leaf.

The challenge the anniversary poses to both leaders is the same: how to achieve détente – how to restore normality, or perhaps go one better than that – without losing face. But if the challenge is the same, it is on Mr Abe that the pressure weighs.

After all, it was imperial Japan that cut a brutal swathe through China and south-east Asia in the 1930s and 1940s, acquiring in the process an enduring reputation for fanatical cruelty. If Mr Abe insists on denying that historical fact, he will leave President Xi with very little wriggle room.

So it was heartening to hear Shinichi Kitaoka, a scholar who is also one of Mr Abe’s trusted advisors, take a sane line. “I want Mr Abe to say, Japan committed aggression [against China],” he told a symposium in Tokyo last week. “Japan fought a war of aggression. It did really dreadful things.”

Can Mr Abe bring himself to repeat that, word for word? If so, his next handshake with President Xi might have the appearance of cordiality.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks