Imran Khan: ‘We need to talk to the Taliban. War is no solution’

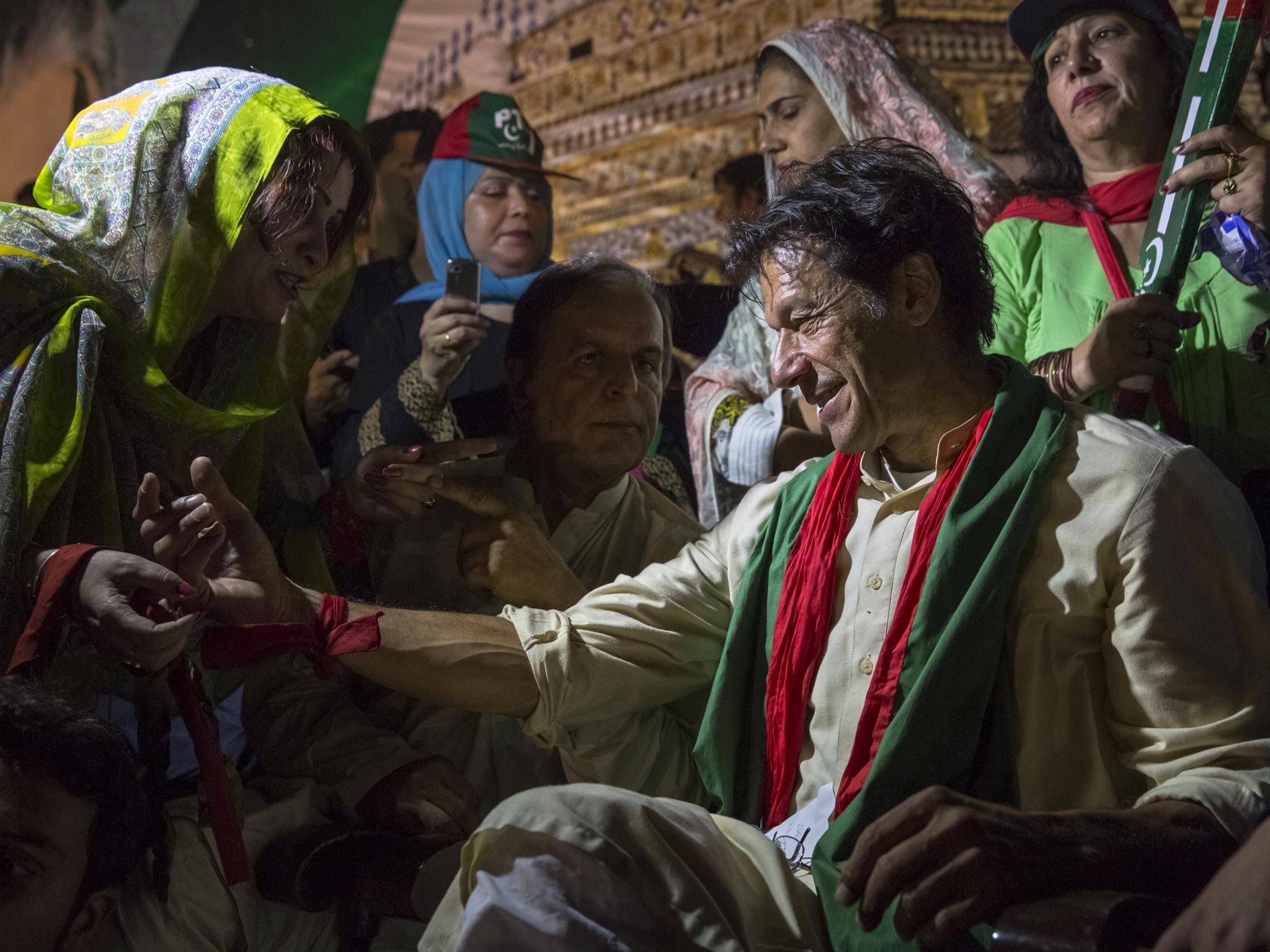

The former cricket legend and opposition leader has been branded pro-extremist for his opposition to military action, he tells Omar Waraich in Islamabad

One year ago, Imran Khan was all the rage in Pakistan. As the 2013 general elections approached, there was great excitement around his campaign of “change”, on an anti-corruption platform that vowed to restore peace and prosperity to Pakistan.

Today, though, the former cricket legend and opposition leader is feeling the pressure that his surge in popularity brought.

His problem, his critics say, is that he is too soft on the Pakistani Taliban, at a time when the group is carrying out deadly attacks across the country.

For the past fortnight, a committee announced by the Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, has been meeting with the militants’ nominated interlocutors to try and hammer out a peace deal.

But those talks are now imperilled as the militants continue to carry out a wave of bombings. Peshawar, the capital of the north-west province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has seen attacks on cinemas, the home of a local peace committee leader, and on Thursday the Taliban claimed responsibility for the killing of 11 Pakistani policemen.

Mr Khan has long insisted that there is no military solution to the conflict and that further military offensives will only lead to more collateral damage, spark reprisal bombings in Pakistan’s main cities, and add to the already ruinous toll exacted on the country’s economy.

“I was against this war from 2001 onwards,” Mr Khan told The Independent, in an interview last week at his hilltop hacienda just outside Islamabad. “In 2004, in my speech to parliament I warned General Musharraf not to send the Pakistan army into Waziristan, because of the history of these tribal people.”

Mr Khan, the leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party (Movement for Justice), insists that the only way out of the seven-year long conflict that has cost tens of thousands of Pakistani lives is through a lasting peace agreement.

Officially, it’s also the position of the government and other parties, but because Mr Khan has been the most vocal on the issue, he has stood out as a lightning rod for criticism.

“I’m against an operation in North Waziristan,” Mr Khan said, referring to plans for the Pakistan armed forces to strike what is seen as the most dangerous of its seven tribal areas along the Afghan border, home to a hornets’ nest of militants. “I think it’ll exacerbate the situation. My belief is that the best thing now is talks. The talks are mainly about disengaging from the American war.”

In Mr Khan’s view, the Pakistani Taliban was emboldened by a two-year campaign by the Pakistan army against them, which the militants saw as being carried out by Gen Musharraf at Washington’s behest. The militants, he said, “see the war as a jihad”.

“Jihad is what is supplying the recruits,” Mr Khan added. “The moment you disengage from the US war, the jihad narrative disappears. The moment that disappears, they don’t have recruits. You actually isolate the hardliners.”

Mr Khan compared his position on negotiations to the recent agreement signed between the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the Malaysian experience of taming a communist insurgency, and US efforts in 2010 to lure the Afghan Taliban to the negotiating table.

Mr Khan’s many critics concede that his view has been consistent. But many commentators and analysts also see it as “naive” and “too soft” on the Taliban. A common criticism is that Mr Khan angrily denounces US drone strikes and protests against them, but doesn’t have the same reaction when militants kill even more civilians in the bombing campaigns.

In a widely read article that went viral last week, the noted columnist Cyril Almeida argued that Mr Khan had used his fame, good looks, and charisma to give extremism an acceptable face.

“The problem with Khan,” Mr Almeida wrote, “the problem for all of us, is as simple as it’s ugly: he has mainstreamed extremism.”

For Mr Khan’s critics, the claim was given substance recently when the Taliban asked him to represent them at talks. Mr Khan declined the offer, and bristled at suggestions that he is indulgent of the Taliban.

“It’s because I’ve always stood for dialogue and said there’s no military solution,” he said. “There’s a powerful pro-war lobby here... Anyone calling for dialogue is being pushed into being called pro-Taliban.”

One area where he has won widespread praise is for his recent campaign against polio. Peshawar, the capital of the province his party governs, was identified by the WHO as the epicentre of polio in the region. Mr Khan and his volunteers have run a successful campaign of immunising hundreds of thousands in recent weeks against the backdrop of violent threats to all polio workers from the militants.

In Mr Khan’s view, the idea of the talks is to speak to the groups who are amenable to an accommodation with the Pakistani state, isolate the hardliners who are irreconcilable, and win over the “people of the tribal areas”. “Then you won’t need an operation,” he said. “You’ll just need a small commando [force] backing the people of the tribal areas, and they themselves will take care of the hardliners.”

“My worry about the operation is there are 700,000 people living there,” Mr Khan added. “There’s going to be massive collateral damage because they’ll be using tanks, guns, helicopters, artillery.”

If there is collateral damage, he believes, the people affected will turn against the Pakistani state. “Anyone losing a family member will seek revenge,” he said. “Revenge means joining the militants. It will strengthen militancy in Pakistan, and the Pakistan army will get bogged down there.”

The chances of success also appear slim to him. Last year, he said, he had a meeting with Mr Sharif and the then army chief Gen Ashfaq Parvez Kayani. “I had a special meeting with the army chief, and he said there’s a 40 per cent chance. You do not take a chance at 40 per cent. You must exhaust all possibilities first.”

But Mr Khan is also open to military action if the talks break down, as seems increasingly likely now. He said his fear was that militants hostile to talks will carry out bombings that will derail the process, as appears to have happened with the latest Karachi attack. “If the talks fail,” he said, “we still have the choice.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks