French universities crisis: Low fees and selection lotteries create headaches in higher education

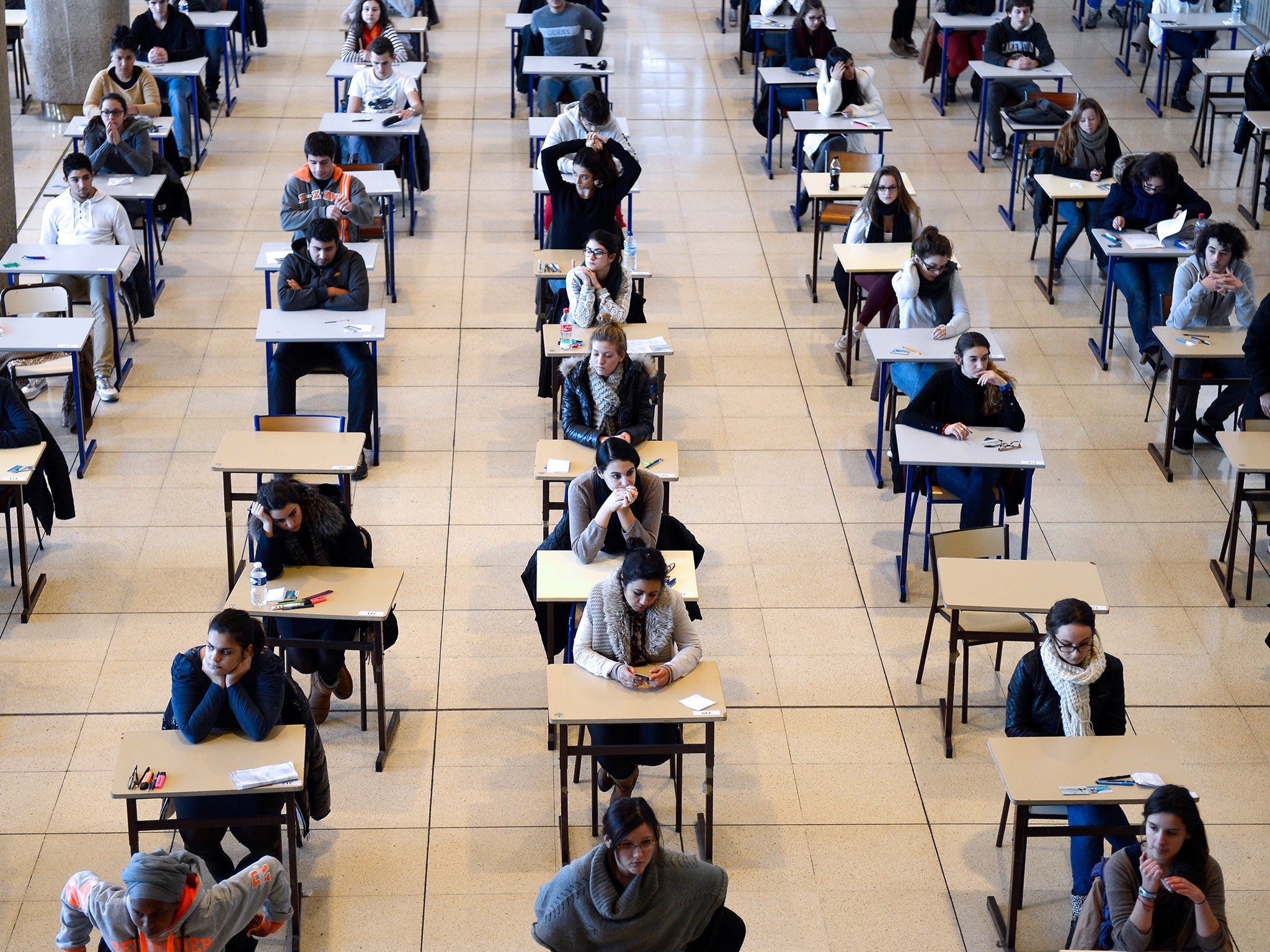

Welcome to the bear-pit of the French university system. There is almost no selection; fees are minimal; classes are gigantic; and the first year failure rate is five times higher than in Britain

Ella, 18, is just beginning her first year of medical studies in Paris. Although she is part of a class of 1,500 students, she has already learned one lesson. Never leave your lecture notes unguarded.

“You could leave your laptop behind and no one would go near it,” she said, “but some students steal your notes and destroy them. They think that, by screwing you up, they improve their own chances of passing first year.”

Welcome to the bear-pit of the French university system. There is almost no selection; fees are minimal; classes are gigantic; and the first year failure rate is five times higher than in Britain.

Two studies published in recent days have cast renewed doubt on the health of higher education in France. No French university proper made the top 100 in the QS world rankings of universities published last week. A survey this week found that foreign exchange students awarded French universities the lowest level of academic satisfaction in the European Union.

There is a growing drumbeat for radical reform – including a report handed to President François Hollande which mentions the S-word – selection.

In the name of “Egalité”, French universities are non-selective and cheap (€180 or £133 tuition fees a year). An extra 65,000 students – the equivalent of four new universities – will enter the system this year, but funding has been cut in the drive to reduce the state budget deficit.

As a result, pre-admission selection of students does occur – but by lottery. Unlucky applicants wind up in the less sought-after courses.

A half century ago, a French education minister described undergraduate life in France as “like organising a shipwreck to find out who can swim”. Nothing much has changed. Under French law, any student who passes their baccalauréat (equivalent of A-levels) by scoring an average of at least 50 per cent has a theoretical right to enter the university course of their choice. Nearly fifty per cent fail their first year. The equivalent failure rate in Britain is 8.4 per cent.

In medical studies, the problem is made worse by a government-imposed quota on the number of doctors allowed to graduate each year. Hence the outbreaks of sabotage through “note-stealing” in Ella’s first-year class.

The recent report to President Hollande suggests that France should scrap, or modify, its cherished “non-selection” policy. Students who take less academically demanding forms of the “bac” should no longer have a guaranteed university place.

Cue indignation on the left and especially amongst the students themselves, who are arguably the greatest victims of the present system.

William Martinet, 27, president of the largest student union, Unef, told The Independent: “We absolutely oppose any form of selection. Any restrictions on access to courses, such as personal interviews or target grades, reduce social mobility. It always penalises young people from poorer backgrounds. For them, the university system is still the best way to success.”

Other students disagree. Florent Louise, a student blogger in Toulouse, says that the present “grotesque” system produces mass education for students who are often poorly guided or unmotivated. Only 27 per cent complete their “licence” (degree) in three years, compared with 75 per cent in the UK. Those who graduate with general degrees find their qualification scorned by employers. “Selection would end this hypocrisy,” Mr Louise said. “The truth is that a university degree in France guarantees you neither a career nor personal fulfilment.”

Critics say the hypocrisy is compounded by the fact that France has two disconnected systems of higher education. The university system proper is non-selective, while the other system – “Les Grandes Ecoles”, finishing schools for the business and political elite – is hyper-selective and lavishly financed. These elite institutions and their feeder schools and receive 30 per cent of the state budget for higher education but take only 4 per cent of the students.

Jean-Loup Salzmann, head of the conference of university chiefs, says the lottery is “the worst of all solutions” – but there is no choice. “The number of students is rising and our resources are being cut… The problem is that too much money is invested in the Grandes Ecoles... They cream off the students who are going to succeed anyway. ”

This is a classically French conundrum. The myth of equality conceals an unequal truth; any attempt at reform has to start with the myth, rather than the reality. Ella, the medical student, is a good example. In theory, she has the same chance of success as her 1,499 classmates. She freely admits, however, that her parents fork out for private courses to help her to survive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments