The end of Schengen? Restrictions by Denmark and Sweden are 'threatening Europe's passport-free zone'

As Sweden and Denmark demand ID to travel between their nations for the first time in 50 years and four other passport-free countries reintroduce checks, the EU’s open border faces its biggest threat yet

Europe’s passport-free Schengen zone is facing the biggest test of its two-decade existence after Sweden re-imposed controls on visitors crossing from Denmark across what had been one of most open borders in the world.

Hours after the measures came into effect, Denmark announced it would slap new controls on its own border with Germany, while Berlin warned that the 26-nation zone of passport-free travel was now “in danger”.

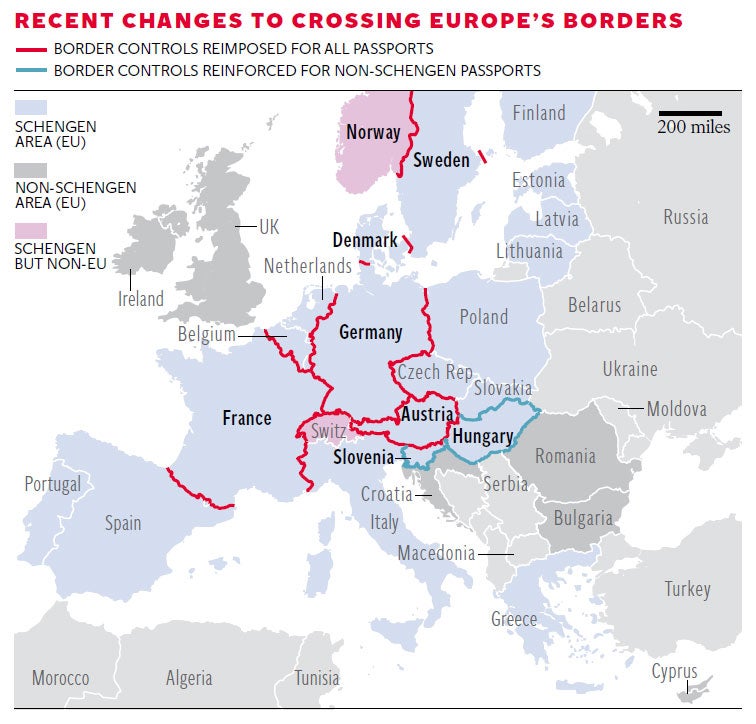

Six Schengen countries – Austria, Germany, France, Sweden, Denmark and non-EU member Norway – have now reintroduced border checks as Europe struggles to cope with an unprecedented influx of refugees and migrants from conflict zones including Syria and Afghanistan.

Danish Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen blamed Sweden for his own country’s introduction of random border checks. “We are simply reacting to a decision made in Sweden. This is not a happy moment at all,” he said. Without action, he said, the checks in Sweden could “increase the risk of a large number of illegal immigrants accumulating in and around Copenhagen”.

Sweden’s new identity-controls target travellers crossing by train or bus from Denmark over the five-mile Öresund Bridge, or using ferry services. Some 17,000 commuters cross the Öresund between Danish capital Copenhagen and Malmo in Sweden daily.

The rules, enforcing an identity check for travellers between the two nations for the first time in half a century, meant rail passengers had to exit their trains and show photo identification at checkpoints in Copenhagen before reboarding to cross the bridge. Direct journeys from Copenhagen’s main station to Sweden were cancelled, with the changes doubling the usual 40-minute commute time.

Denmark’s rail company, DSB, along with ferry and bus companies, conducted the checks. Sweden’s state-owned train operator, SJ, said last month it would stop its services to and from Denmark if such a measure were introduced, as it would not have time to conduct the checks.

Danish Transport Minister Hans Christian Schmidt described the new measures as “extremely annoying” and suggested Sweden should pay for the checks, which DSB estimates will cost around £100,000 a day.

Sweden’s new controls represent a turnaround for the Nordic nation which has taken in more asylum seekers per capita than any other European country. Although the left-leaning government initially welcomed the Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan refugees who swept across Europe last summer, it only expected about 100,000 to make it to Sweden, many of them through Denmark. The final figure was more than 160,000 and strained local essential services. Such scenes have been replicated across the continent, with more than one million refugees and migrants having arrived in Europe during 2015, and nations such as Hungary and Slovenia reinforcing the exterior borders of the Schengen zone.

The new controls are not just a reverse of the 1995 Schengen accord, but also a setback to the post-1945 Nordic Council tradition of open borders that includes the five-nation Nordic Passport Union, which came into force in 1957. It was “a dark day for our Nordic region”, said former Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel responded by calling for a “joint European solution”, on the issue of refugees and migrants, her spokesman Steffen Seibert said. “The solution won’t take place on national borders between country A and country B,” he added. German foreign ministry spokesman Martin Schaefer said: “Schengen is very important but it is in danger.”

However, Germany itself imposed controls at its Austrian border last September, just days after offering refuge to all Syrian nationals. Under Schengen rules, members can ask for a six-month exemption from the agreement on free circulation in exceptional circumstances.

Norway said last week it would tighten its rules and turn back asylum seekers without visas. Its right-leaning government said the draft law would create one of Europe’s toughest immigration systems, making it more difficult to claim welfare benefits, and only allowing family reunifications after four years of work or education in the country. Around 30,000 people sought asylum in Norway last year, most crossing the border from Sweden.

The UN’s special representative for migration, Peter Sutherland, said Europe should improve its external border controls and speed up asylum processing rather than retreating from Schengen. “Recreating borders across the EU will not answer anything, least of all, the humanitarian crisis we face,” he said.

Elizabeth Collett, director of Migration Policy Institute Europe, warned that the new border measures would do little to stop refugees. “The political message to neighbours is, ‘It’s your turn, you deal with it.’ But that just passes the problem along,” she said. “None of the drivers that have led people to migrate have changed, given the conflict in Syria and instability elsewhere.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks