The mystery of CloClo: did he write 'My Way'? And was he killed while changing a lightbulb?

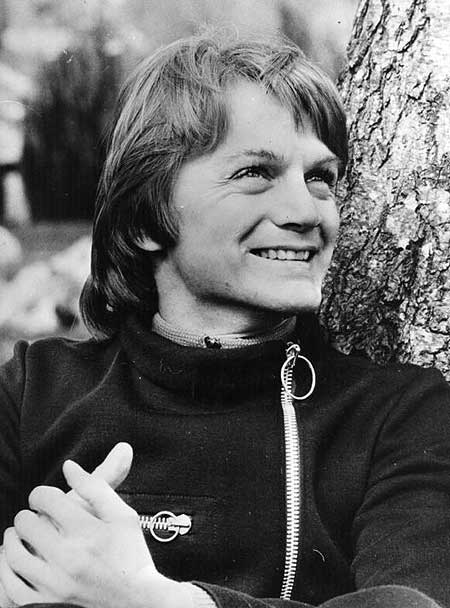

Thirty years ago today, a short, bleach-blond, 39-year-old man with bow legs stood up in his bath in his Paris apartment and tried to fix a light bulb. Thus ended the life of Claude François, France's second most successful pop singer of the 1960s and 1970s.

His life may have ended but his career has endured. Three decades later, Claude François – CloClo – remains one of France's biggest-selling recording artists. One of the songs that he co-wrote still rakes in more royalties from abroad than any other piece of French music, popular or classical. In French, it is called "Comme d'habitude". In English, it is one of the most loved, and loathed, of popular songs. With words rewritten by Paul Anka, it became the Frank Sinatra classic, and drunken karaoke anthem, "My Way".

Across the Channel, the 30th anniversary of the death of François has produced an avalanche of books, television and radio programmes and CD compilations of his French hits.

Like his great rival, Johnny Hallyday – a man that he detested – CloClo never had any hits outside the French-speaking world during his lifetime. At the time of his death, however, he had just made a breakthrough in Britain, packing the Royal Albert Hall with 5,000 hysterical, mostly female, fans.

If he had lived, he might have done something that Hallyday never did. He might have peddled "le pop-rock Français" – mostly a rip-off of American and British music – back to "les Anglo-Saxons".

Three decades after his death, why does CloClo remain such an iconic figure in France? Did he really die while trying to change a light bulb? Did he really write "My Way", or merely claim the credit for others' work?

François once admitted that he sang "like a duck". He was small, with thin, bandy legs. He had an oversize head and, originally, an oversize nose. His public image was of a boy-next-door who became an animal-loving family man. In truth, he was a monster: an egotistical, perverse, mean, ill-tempered control freak and perfectionist.

Far from being a family man, he hid the existence of his second son for five years because he thought that being a father of two would destroy his boyish image. He turfed his second wife and two sons out of his country estate south of Paris to make room for a new, Finnish girlfriend.

His first wife, Janet Woollacott, was a British dancer. When they were a penniless engaged couple in Monte Carlo in 1961, the young François spent all their savings on his own glittering wedding suit, leaving nothing for the costume of the bride. He said that this was justified because, as a future pop star, he could wear the suit on stage. Janet could not wear her wedding dress while dancing.

Later, when they moved to Paris, he locked her into their small flat to prevent her from meeting other men. Unsurprisingly, she left him for another singer just before he became famous with an Everly Brothers re-make, "Belles, belles, belles" in 1962.

Claude François was, in several ways, ahead of his time. He ran his career with the energy and care of a successful business executive. He was one of the first pop artists to make small films to go with his songs.

He made his roadshow into a glitzy spectacle, with female dancers – the "Clodettes" – and special effects. He ran his own celebrity magazine, his own record label, even his own perfume company and erotic magazine (for which he took most of the photographs).

In all of this, CloClo was the polar opposite of his great rival. Johnny Hallyday had a bad-boy reputation but was, by all accounts, always a straightforward, pleasant man. CloClo, by contrast, posed as an angelic pretty boy but was actually a tortured soul, driven by a determination to succeed and to control every detail of his life and career. He was notorious, in particular, for fiddling with the texts of songs.

In 1967, a young songwriter called Jacques Revaux offered CloClo a rather slow, lugubrious tune called "For Me". The singer altered the melody slightly, wrote new words and turned it into an elegy to dying love called "Comme d'habitude".

Paul Anka rewrote it as a soaring bittersweet statement of defiance. In 1969, Frank Sinatra made it one of the most successful pop songs of all time.

So did CloClo actually "write" "My Way"? Certainly, it would never have existed without him. Geneviève Rembaux is a TV director who made a documentary, shown last week, on the singer's life and has co-authored a new book with his one-time Finnish girlfriend Sofia Kiukkonen. She concludes that François was driven to succeed by three traumas.

The first was his family's expulsion from a wealthy life in Egypt in 1956. François's father was a senior manager in the Anglo-French Suez canal company. When President Gamel Abdel Nasser nationalised the canal, the family found themselves penniless.

The second trauma was his father's decision to turn his back on his son when he became a musician in Monte Carlo in 1957. The third trauma was his abandonment by his beautiful, long-suffering first wife, Janet.

Mme Rembaux says: "He turned his pain into a kind of motor. He would be famous and loved or he would be nothing."

Conspiracy theories continue to swirl around CloClo. Was he secretly gay? Was he murdered? The flurry of new works on his life gives a resounding "non" to both questions.

Bad-tempered perfectionist that he was, the sight of a flickering light bulb as he lay in his bath overcame his common sense.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments