Isis in Libya: How Muhammar Gaddafi’s anti-aircraft missiles are falling into the jihadists' hands

As the militants exploit the chaos in the country, there are fears they could target civilian airliners

Deep in the Sahara, in the sun-baked Libyan town of Sabha, a ragtag group of gunmen agreed to show Timothy Michetti their most prized weapons.

Mr Michetti, an experienced investigator for a London-based company that tracks the sources of small arms in conflict zones, travelled there on a hunch. Local fighters, he reckoned, may have some of the shoulder-held anti-aircraft missiles that disappeared when rebels ousted the Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

In the sweltering heat, the gunmen unveiled a small arsenal: four Russian-made SA-7 missiles and two later models of the SA-16 variety. The heat-seeking missiles are capable of shooting down a civilian airliner.

The fighters said they acquired the weapons from nomadic smugglers on their way to illicit weapons bazaars in neighbouring Chad. But after comparing the missiles’ serial numbers to those in his company’s database, Mr Michetti confirmed his hunch: these had been Gaddafi’s arms.

The missiles had no grip stocks or launchers, which rendered them unusable, but that wasn’t much of a relief. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of working Libyan shoulder-held missiles remain unaccounted for, American and UN officials say; some have probably fallen into the hands of Isis jihadists, US intelligence sources say. They add that as Isis continues to exploit Libya’s four-year civil war between two main rival factions, the group is likely to use these weapons as it fights to widen its strategic foothold in Libya to include the country’s oil fields. There’s some evidence the group has already succeeded.

No one has downed a passenger plane using stolen Libyan missiles, known in military parlance as “manpads” or man-portable air defence systems, yet the likelihood that Isis now has these weapons in Libya means the group or its affiliates could be well-equipped to strike at civilian aircraft in Africa or Europe, US officials say. “These missiles are very portable and easily smuggled,” says a senior State Department official who leads a special team given the job of securing the Libyan missiles. “All it takes is for one to get through.”

Despite the dangers these Libyan missiles pose, the Obama administration has effectively stopped trying to locate and destroy them, State Department officials say. The main reason is that it’s too dangerous to go looking for them in Libya.

It’s unclear how many missiles remain at large. According to both US and UN officials, Gaddafi accumulated an estimated 20,000 shoulder-held manpads during his four decades in power. Yet these officials stress that attrition, poor maintenance and the Nato bombing campaign during the 2011 revolution reduced that number by the time the dictator was overthrown.

Not long after Gaddafi’s fall, President Barack Obama dispatched the special US team to Libya, which located and destroyed about 5,000 missiles. But the team leader, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive security issue, acknowledges he has no idea how many manpads are missing. “There’s a large number still there in Libya, where some of the larger militia groups still maintain the stocks that they originally took control of back in 2011,” he says. Others are in the hands of Libya’s smaller fighting groups, and arms traffickers have smuggled some out of the country to feed the conflicts in Syria, the Sinai, Nigeria and Mali. “We might never know where they went,” the team leader adds.

On 11 September 2012, the manpads team suffered a major setback. Islamic militants attacked a secret CIA station in Benghazi, killing four Americans, including the US ambassador Christopher Stevens. The loss of the CIA post, which had been tracking the whereabouts of Gaddafi’s looted weapons, eliminated one of the team’s critical sources of intelligence. The team pulled out of Libya less than two years later, when the US embassy in Tripoli closed because of the deteriorating security situation.

“Because it’s an active conflict zone, the US team has no ability to go into Libya to locate and secure manpads,” says another team member. “Frankly, we have no leverage in a conflict to ask people to give up weapons.”

These days, team members work from a State Department annex in Washington, helping other governments in North Africa and the Sahel secure their weapons stocks. In an odd turn of events, the State Department has turned to several European-based private groups to carry out one of its other long-standing missions in Libya: locating and destroying mines left over from the Second World War.

Some observers suggest the administration gradually shifted its attention from finding the missing manpads to the war in Syria and the nuclear deal with Iran. “There was a huge flurry about the missiles right after the fall of Gaddafi,” recalls Rachel Stohl, an expert on small arms at the Stimson Centre, a Washington think-tank.

“Then it was quiet for about two years. When we began seeing evidence that the missiles were showing up in Mali and other countries, the buzz returned. But since then, it’s fallen off the radar because of other, higher priority issues. And that’s troubling. These weapons can cause catastrophic damage to a civilian or military aircraft, killing hundreds of people.”

It’s unclear why no Libyan combatants have used the looted missiles to target a civilian airliner. “That’s the million-dollar question,” says Matthew Schroeder, a researcher for the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, another organisation that traces the source of weapons. Some analysts note that many of the country’s armed groups have no military training and don’t know how to operate the missiles. More important, they add, the men who control Libya’s two biggest militias and aspire to lead the country aren’t interested in downing a civilian plane, which would be likely to halt flights in and out of the country.

Libya’s criminal gangs don’t want the airports closed because they depend on them for smuggling. And with missiles fetching as much as $12,000 (£8,400) on the black market, the militias prefer to sell them when they need cash, notes Savannah de Tessières, a member of a UN panel that is also investigating the whereabouts of the looted weapons.

In Egypt, however, anti-government jihadists haven’t shown such restraint. In January 2014, Islamic fighters belonging to a group called Ansar Bait al-Maqdis used what Egyptian and Israeli officials say was a looted Libyan shoulder-held missile to shoot down an Egyptian military helicopter in the Sinai, killing five soldiers. Later that year, the group pledged its obedience to Isis. In November, Isis’s Egyptian affiliate took credit for planting a bomb aboard a Russian passenger jet, killing all 224 passengers and crew. The attack marked the affiliate’s shift to Isis’s indiscriminate killing of civilians.

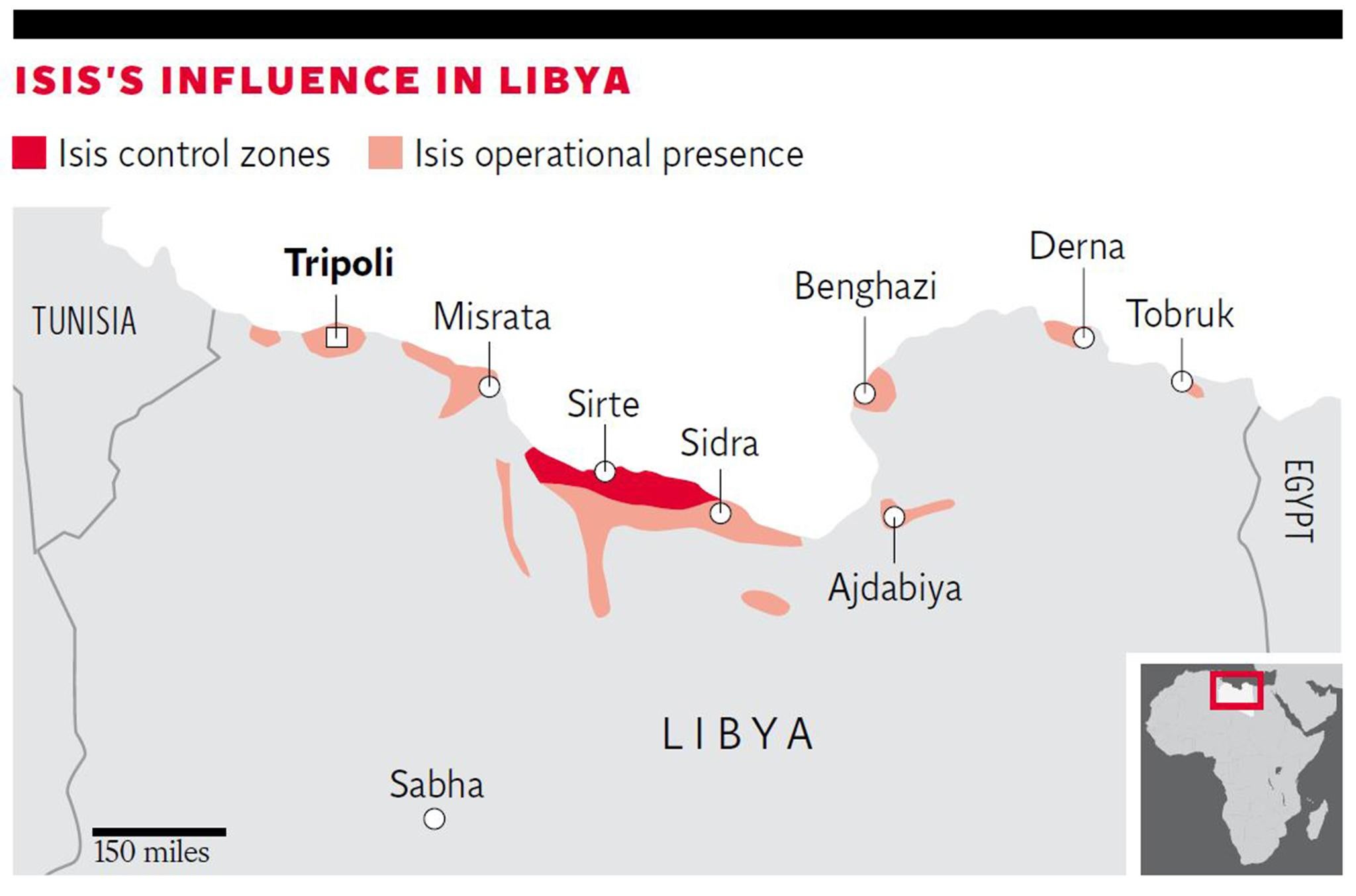

US, European and Arab officials now fear the Libyan civil war may lead to Isis missile attacks against civilian planes in North and West Africa, as well as in Europe. The chaos in Libya has allowed Isis to carve out a 150-mile enclave along the country’s central Mediterranean coast, with the city of Sirte at its centre. The Pentagon says the group has as many as 6,500 fighters in the country, but other intelligence sources say the group’s ranks are swelling rapidly, putting the number of Isis combatants in Libya at 10,000.

Intelligence officials say the group’s growing presence in Libya is part of a larger strategic plan. As Isis loses territory and oil revenue to coalition forces in Syria and Iraq, its leaders view Libya as a redoubt on which it can fall back, a new source of oil money and a base from which to spread its influence across North and sub-Saharan Africa. From Libya, these sources say, Isis can also piggyback on the refugee flow across the Mediterranean to strike at Europe.

For more than a month, President Obama has been under pressure from his military and national security aides to launch a major bombing campaign in Libya against Isis. So far, he’s resisted, opting instead to conduct targeted air strikes on the group’s commanders and one of its training camps along the Tunisian border. There are reports, however, that a multinational force, made up of troops from Italy, Britain, France and Spain, is poised to take on Isis on the ground in Libya, with the US providing special operations troops, as well as logistical and air support. But the Americans and the Europeans won’t agree to the operation until Libya’s rival factions form a unity government.

In the meantime, some of the more unsettling predictions about Isis in Libya may prove prescient. In February, Isis said it shot down a Libyan government MiG-23 fighter jet west of Benghazi as it bombed an unaffiliated Islamist militia. The group released a video of the attack, which the internationally recognised government in Tobruk confirmed. After analysing the video, US intelligence officials say it appears Isis used a missile to bring down the aircraft. Isis claims it has downed two other Libyan warplanes with missiles since January, but the government insists both crashed because of “technical problems”. If the next plane is a civilian airliner, that excuse may not fly.

Additional reporting: Jeff Stein in Washington

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments