Fairtrade: Is it really fair?

As more than 70 countries celebrate World Fair Trade Day on Saturday, Sarah Morrison examines the scheme's pros and cons

It is trade, of that there is no doubt. Some £1.3bn is spent on Fairtrade-badged goods in the UK. But nearly two decades after the launch of the scheme, the question that increasingly vexes consumers as they make their purchases is: is it really fair?

The UK is the world's biggest fair-trade market, and it continues to grow. The first three products to showcase the Fairtrade mark hit the shelves in this country 18 years ago. Now, days ahead of World Fair Trade Day, there are more than 4,500 products carrying the familiar logo in our shops.

The scheme was set up with the anything-but-simple mission of providing "better prices, decent working conditions, local sustainability, and fair terms of trade for farmers and workers in the developing world". Farmers who pay for certification are assured a minimum price – which can never fall below market level – and a premium to invest in their communities.

Sales of the fair-trade goods increased by 12 per cent in the UK between 2010 and 2011, and this year alone, Mars – the third biggest confectionery brand in the UK – will switch Maltesers to Fairtrade, representing more than a 10 per cent increase in total sales. Fairtrade has turned to certifying the gold industry in the past two years and is expecting to announce new standards for freshwater prawns this summer. Almost 40 per cent of all our bananas are now Fairtrade.

Despite becoming increasingly mainstream, the Fairtrade label has persistent critics. It is attacked by those on the left who say it has sold out and given in to the market. Pundits on the right argue that it distorts markets, exaggerates its claims, prices out the poorest farmers and perpetuates inefficient modes of production.

In the week when more than 70 countries will celebrate the notion of fair trade as a "tangible contribution to the fight against poverty", The Independent on Sunday looked behind the label to answer one pressing question: just how fair is fair trade?

'The whole town depends on mining – we need support'

Harbi Guerrero Morillo, 40, lives with his wife and one-year-old daughter in Colombia. For the past 14 years he has been running a mine, providing work for 30 workers. In his community, about 70 per cent of people are employed in mining-related activities and earn around £220 a month for their work. Almost 400 families benefit from the gold production. Mr Morillo's co-operative is in the process of becoming certified with Fairtrade and Fairmined, in order to become one of only a handful of mines to produce Fairtrade gold.

"We would take pride and show off our certified community because it would show that our gold is clean, exported and seen in a positive way. Sometimes the industry is frowned upon, and there are concerns that if mines don't comply with legislations, they will be closed down. Here, the whole town depends on mining – we need support. This certification could work as a road map for mining and it could open us up to how we could improve our communities and network with other miners. It is about legitimising my work – that is very important."

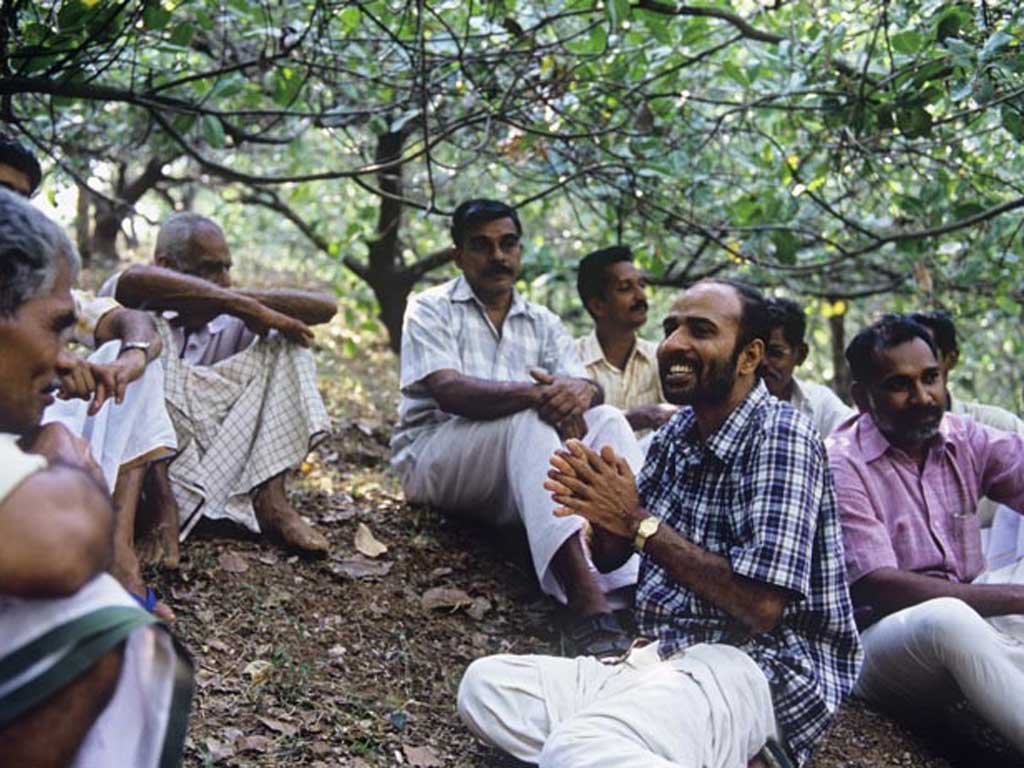

'The fair-trade price does not change throughout the season'

Tomy Mathew, 50, is a spice and nut farmer from Kerala, India. He was one of the founding members of his local fair-trade alliance, which was established more than six years ago, after his region suffered an "agrarian crisis".

"Between 1992 and 2006, there was a terrible economic crisis for agriculture in Kerala. All the prices fell and this made us look for markets that offered fair deals to farmers. This year, the market price for cashews was about 62 rupees per kilo (71p). The fair-trade price came in at 75 rupees per kilo (86p). It's not the difference between the market and fair-trade prices that makes the most difference; it is the fact that the fair-trade price does not change throughout the season. It costs us $3,000 a year to get certified, but in the first year, we received a 75 per cent subsidy. It might be difficult to pay, but I wouldn't want them to lower the price – it ensures the credibility of the system."

'Fairtrade is the way forward – we can make a living'

Moses Rene, 34, is a banana farmer who lives with his wife, Robertina, in St Lucia. He works on their farm eight hours a day, six days a week, and is involved in his local Fairtrade farmers' group, a part of the Windward Islands Farmers' Association. Two decades ago, the Windward Islands supplied 60 per cent of UK bananas; now the Islands' share has plummeted to 9 per cent, displaced by lower-cost bananas from Latin America. Supplying his crops to Sainsbury's and Waitrose, Mr Rene says he thinks fair trade is the only way forward for his industry.

"My local group of 80 members signed up to Fairtrade at an important time. It was at the point when farmers here were thinking of stopping producing bananas; we just couldn't compete. Farmers here get almost double the rate for a box of bananas under Fairtrade and also a $1 premium per box. This has given me some stability to borrow from the bank and I set up a preschool for 34 children in my area.

"Individual farmers here pay about 400 Caribbean dollars (£91) per year to be registered and I do think this is a little too much, especially when your production is low and you have high costs. But, we are more empowered here. We know what is taking place in the market and we have closer links to retailers. They tell us if they have problems and we do whatever we can to try and fix them.

"I know I can't only depend on one product and I have diversified into others, but I know my passion, my love and my future is in bananas. For as long as there is a market, I'll be a farmer. Fairtrade is the way forward – it is a way of keeping poor producers like myself earning a living."

But is it FAIR?

YES: It puts people back at the heart of trade

By Harriet Lamb, Fairtrade Foundation

Fairtrade does what it says on the tin: it is about better prices for smallholder farmers and workers in developing countries. Fairtrade addresses the injustices of conventional trade, which too often leaves the poorest, weakest producers earning less than it costs them to grow their crops. It's a bit like a national minimum wage for global trade. Not perfect, not a magic want, not a panacea for all the problems of poverty, but a step in the right direction.

Free-market economists complain that Fairtrade benefits only a small number of farmers, penalising those outside. This is plain wrong. In fact, the evidence suggests that the opposite is true. Research in Bolivia, for example, found that coffee producers outside Fairtrade were able to negotiate higher prices: Fairtrade had become a price setter. Fairtrade farmers also share their knowledge in trading. For those inside the system, our research shows that through the minimum price guarantee, farmers have more secure and stable incomes. A group of rice farmers in India invested their premium in buying a tractor and a land leveller; productivity increased by 30 per cent.

Other critics ask why we are working with retailers or big brands like Cadbury's and Starbucks. Our answer is that only by mainstreaming Fairtrade will we be able to reach more producers. So we are unapologetic in our commitment to scale up. By doing so, moreover, we begin to affect all business behaviour.

A favourite question is why don't we work with UK farmers. We recognise that many farmers in the UK face similar issues to farmers elsewhere, but Fairtrade was established specifically to support the most disadvantaged producers in the world - like the tea-growers of Malawi, who don't even have drinking water in their villages. I always buy my cheese, pears and carrots from my local farmers' market - and enjoy Fairtrade bananas, tea and coffee. It's two sides of the same movement to put people back at the heart of trade. Surely you cannot say fairer than that.

NO: Other schemes are just as valuable

By Philip Booth, Institute of Economic Affairs

Private certification schemes are the unsung heroes of a market economy. They are far more effective than state regulation. It is therefore with a heavy heart that I have always had reservations about Fairtrade-labelled products. The foundation pounces on critics with its well-oiled publicity machine, always responding with anecdotes. But doubts remain.

There are many ways in which poor farmers can get better prices. They can do so through speciality brands, via traditional trade channels and using other labelling initiatives. Does Fairtrade help? The evidence is limited, but even proponents of Fairtrade would argue that only about 50 per cent of the extra money spent by consumers is available to spend on social projects, and others have suggested a figure much closer to zero. No clear evidence has been produced to suggest that farmers themselves actually receive higher prices under Fairtrade.

Fairtrade cannot help all farmers. Some poorer or remote farmers cannot organise and join up; others cannot afford the fees; still others will be working for larger producers who are excluded from many Fairtrade product lines. Against that background, "Fairtrade absolutism" does not sit well. Fairtrade schools have to do everything possible to stock Fairtrade products - but, what about speciality brands produced by individual farmers? What about Rainforest Alliance products? Are poor producers to be expected to pay the costs involved to join every labelling scheme?

Fairtrade is a brand that promotes itself the way all brands do. As noted, the brand is prominent in schools. It is worrying that its PowerPoint presentation shows graphs of commodity prices that stop in 2001 and graphs of the coffee price relative to the Fairtrade minimum price that stop in 2006. The picture since then tells a different story. This is marketing, not education.

Fairtrade may do some good in some circumstances, but it does not deserve the unique status it claims for itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks