Alan Clark was not 'wonderful'. He was sleazy and cruel

The diarist and Tory minister made his wife wretchedly miserable

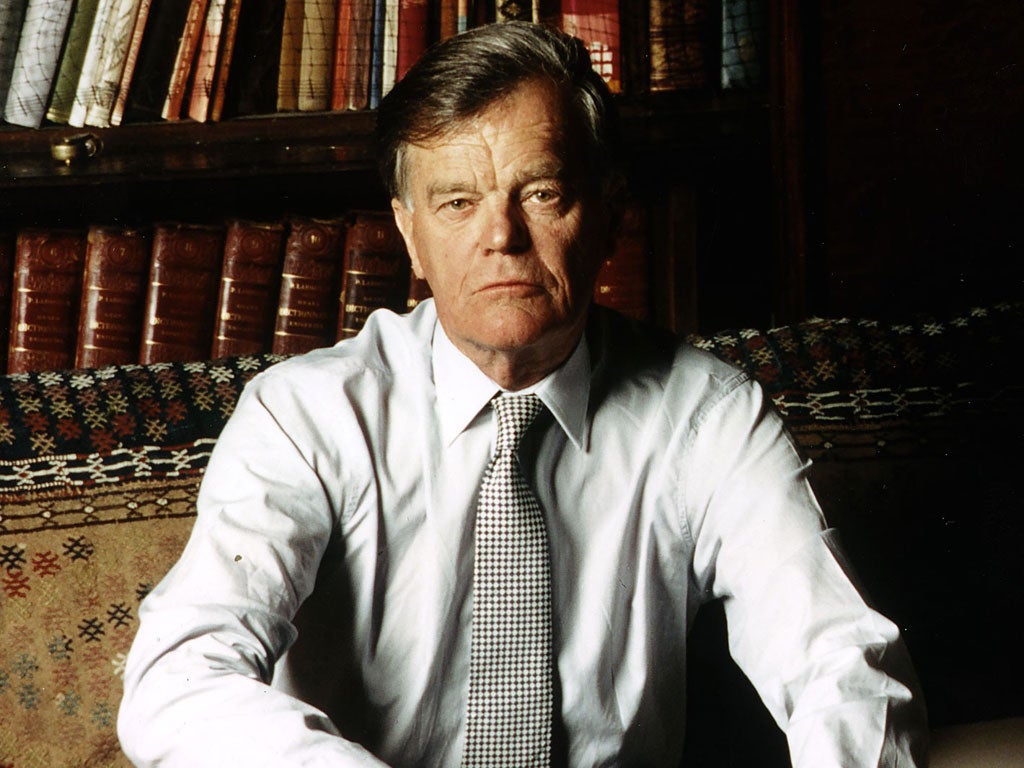

Oh dear, not Alan Clark again. Ten years after the death of the so-called "Samuel Pepys of the 20th century" out comes the official biography. On the BBC Today programme yesterday the book's author, Ion Trewin, described how "wonderful" Clark was. This is the popular view, reinforced by the way in which that marvellous actor John Hurt portrayed Clark's own account of himself to a mass audience, in the BBC dramatisation of his diaries.

Alan Clark was not wonderful. He was sleazy, vindictive, greedy, callous and cruel. He was also a thorough-going admirer of Adolf Hitler, although his sycophants persisted in thinking that his expressions of reverence for the Fuhrer were not meant seriously. They absolutely were.

When Alan Clark died, in September 1999, the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, led the tributes, saying: "We will all miss him". One MP had the courage to offer an honest view of his late colleague: David Heathcoat-Amory – who had the genuine article's ability to see through Clark's phoney imitation of the upper-class Englishman. Heathcoat-Amory told the BBC that "he wasn't a particularly nice man. He could be very cruel with colleagues. One incident that sticks in the mind was when we were having a whip-round for a colleague and he [a multi-millionaire] refused to chip in ... I also think he was very conscious of his own image and status, and his own reputation as a diarist."

That rang true. When the London Evening Standard began publishing some spoof Alan Clark diaries, he sued them for a considerable sum of money, although it must have been clear to any reader that these were nothing more than a form of humorous homage. Yet Clark, for all the witty demolitions of his colleagues in his diaries, took himself very seriously indeed – it was a source of great bitterness to him that neither Margaret Thatcher nor John Major could take at all seriously his insistence that he should be Foreign Secretary.

He made it to Minister of State for Trade, however, in which role he did something truly wicked. At the time, this country had an embargo against selling weaponry to Saddam Hussein. Clark did not agree with this policy, and so gave the nod and a wink to a company called Matrix Churchill to sell machine tools to Saddam, which he knew were for military use. This was against the law, so when HM Customs discovered the shipments, the Matrix Churchill executives were arrested. They protested that the then Trade Minister Clark had given them the all-clear; but when he was visited by the police, he lied and said that he had done no such thing.

So the executives went on trial – and would have received substantial prison sentences, were it not for the fact that the judge overturned so-called ministerial public interest immunity certificates, which had kept from the court documents revealing Clark's involvement. Clark, of course, had signed those certificates, and must have thought that this would end any chance of his lies being uncovered.

Immediately, the Matrix executives' lawyers put to Clark in the witness stand the incompatibility between his remarks to the police, and what was now being revealed. Clark drawled, "it's our old friend economical... with the actualité": in other words, he admitted that there had been a conspiracy between him and the Matrix Churchill executives to disguise the nature of the exports to Saddam. The trial collapsed – and Clark became an instant hero. It was felt that he had told the truth in the dock, and thus saved the defendants from unjust incarceration. The truth was that Clark had been content to see the men locked up on the basis of his perjurious evidence – for which he should have been prosecuted – and only came clean when the forced disclosure of documents he had connived in suppressing had put him on the spot.

It turned out that Clark had earlier explained his motives for clearing the exports to Saddam: "The interests of the West were well served by Iran and Iraq fighting each other, the longer the better." He was indeed a notable historian of wars, one of his most acclaimed works being Barbarossa, an account of the Eastern Front in the Second World War. He was intent on proving Hitler's talent as a military leader, but over the years it became clear that there was more to it than mere technical admiration of Hitler the war strategist. In 1981 his diary records: "I told Frank Johnson that I was a Nazi; I really believed it to be the ideal system, and that it was a disaster for the Anglo-Saxon races and for the world that it was extinguished."

Johnson, who was then on the staff of The Times, gulps and tells Clark that he can't really mean it. Clark really did mean it. But even when he complains in his diary that Johnson "takes refuge in the convention that Alan-doesn't-really-mean-it", his readers continue to believe that this is all an uproarious joke. Yet, and this is to his credit as a diarist, he does not attempt to mislead his readers about his true opinions: at one point he records his thoughts of defecting to the National Front, and when two NF emissaries come to visit him he writes, "How good they were and how brave [those] who keep alive the tribal essence."

All this filth has been submerged by the tidal wave of obsession with Clark's sexual exploits. On that score Trewin's biography will not disappoint. We knew that the 30-year-old Clark married the 16-year-old Jane Beuttler in 1958. Yet Trewin has unearthed the following diary entry, written when Clark's wife-to-be was just 14: "This is very exciting. She [Jane] is the perfect victim, but whether or not it will be possible to succeed I can't tell at present."

He did succeed in the endeavour of making this child a "perfect victim": in the course of their marriage he made her wretchedly miserable with his continuous betrayals. Sickest of all, perhaps, was the way in which on his death-bed he made this much younger woman promise him that she would never remarry. Naturally his "perfect victim" consented.

Again, the reading public seems to find Clark's frenzied extra-marital rutting merely amusing: or perhaps it is just that they appreciate his lack of hypocrisy in admitting all to his diary. They should consider what it was like to be in receipt of his unwanted attentions. Some years ago the (married) journalist Minette Marrin recorded her own experience of it. They had both been invited to a "political" dinner at a private house. He instantly pressed himself on her in a most unsubtle way, demanding that she leave their hosts, join him for a private dinner and then...

Marrin recalled: "He thought 'no' was a form of flirting ... When at last he came to believe that I was impervious to his charms and would not rush off with him into the night, he turned to me with a particularly vicious look. And this is what this self-styled gentleman, this intellectual, this flower of our civilisation, then said: "Well, fuck you then. Fuck off. I'm not talking to you any more."

I think it would be better if we heard no more about the "wonderful" Alan Clark.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments