Laurie Penny: A papier-mâché puppet and a badly tuned guitar... how to go on strike when you haven't got a job

Whatever happens on 1 May, it is doubtful that capitalism will fall

You all need to get jobs!" yelled the woman at the line of students and unemployed graduates marching down from New York's Union Square. Most of them would have agreed with her. Many would have argued that that, in fact, was why they were there in the first place, since half of all 18- to 25-year-old Americans are currently unemployed or underemployed.

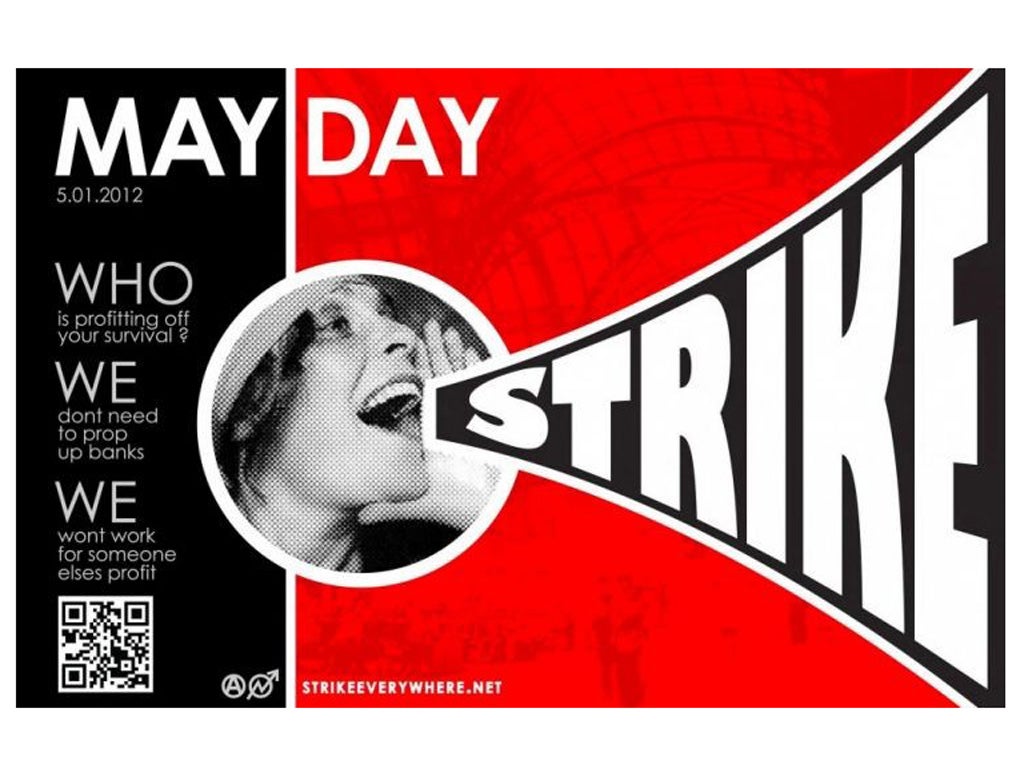

All over the world, "get a job" is the challenge traditionally hurled at young people taking to the streets – as though wage labour of any kind would make them shut up and behave. But what happens when getting a job is almost impossible? What happens, after 18 months of protests, riots, police brutality, show trials and public backlash, is a May Day general strike.

May Day is, among other things, International Workers' Day. For almost 150 years, it has been a day for big, brassy demonstrations of left-wing solidarity across the world – although, significantly, no longer in the US, where the tradition began with the fight for the eight-hour working day after the civil war.

This week, however, the new youth movements, including the loose collection of students, anti-capitalists, anarchists, shop workers, vagrants, hackers, hippies, neo-utopians and teenage runaways known as the Occupy movement, are scheming to bring the scattered left together again. In the middle of a US election year that has already descended into arguments about which White House candidate is the greater dog-lover, the plan is somehow to force financial justice for actual humans back on to the agenda. Plans are mustering to picket banks, blockade roads and bring city centres juddering to a halt. "We will fight for the rights of all immigrants, all workers, all people," claim pamphlets scattered across New York.

The people who wrote them come armed with badly tuned guitars, huge and horrifying papier-mâché puppets, an insatiable energy for organising and almost nothing to lose. The global media machine is rapidly losing interest in watching urban tent cities being smashed up by police, and, with the eyes of the world turning away, a curious thing is happening: Occupy is beginning to adopt the centuries-old language and tactics of organised labour. That includes support for a general strike. The question raises itself, though: in a world where few young people have jobs, and fewer of those who do have full-time jobs, and fewer of those who do have contracted, union jobs, and almost nobody can take the risk of speaking up at work – how can a strike work in practice?

"No work! No school! No housework! No shopping! No banking!" demand the posters wheat-pasted on hoardings and billboards all over the city. "May Day – Everything Stops!" warns the graffiti scrawled in the lavatories in art bars. The call for a general strike, in this new age of networked protest, organised online, via back channels and affinity groups of desperate people in student flophouses, seems to be as much about mood as it is about strategy – in the way that one might call, say, for a general party atmosphere.

It certainly looks exciting. Where the early historians of the French Revolution warned about "poor lawyers" and other unemployed professionals revving the engines of social discontent, they might well have added: and the unemployed graphic designers, coders and arts graduates. Flashy home pages for strikes in Oakland, LA and solidarity actions in London whisper promises of taxi blockades, million-strong marches, a massive reinvigoration of the global left. Whether or not it ends up with 300 people kettled in a park remains to be seen.

They can make great websites, but is it actually possible for young, frustrated people to withdraw their labour meaningfully? Since attacks on unions, precarious jobs and mass unemployment are a great deal of the problem for the poor and undocumented, how can a "general strike" of the dispossessed and workless actually hurt the so-called "1 per cent"? With its simultaneous calls for an end to all wars, tax evasion, wage repression and mortgage foreclosure, the effort seems set up to fail by traditional standards. Whatever happens on 1 May, it is doubtful that capitalism will fall.

That's what we do, though, isn't it, on the left? We set ourselves up to fail. We allow ourselves to fantasise about a world richer and freer and fairer than the one we live in, and we try to make it together out of what we have – which may not be more than a mobile library, a lot of papier mâché and the internet, but sometimes that's just enough to change the mood of a nation. And even when we are disappointed over and over again, and we end up standing in the cold looking ridiculous, or see our friends arrested and our ideas ridiculed in public – even then we keep trying until we can't bear to try any more, at which point we have a strong cup of tea and continue. Or we join hedge funds and cover the mirrors in our houses. For those who continue to envisage a future where human beings can live with dignity whatever their race, gender and social status, being set up to fail hasn't stopped us yet.

Whatever future these young people collectively create – and sooner or later, they'll have to come up with one – the meaning of direct action, the meaning of work, and the meaning of success and failure itself will be redefined. That's not something to dismiss in haste. Not even if it involves more papier mâché than is strictly necessary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments