Peter Popham: Libya is peering into a vacuum of Gaddafi's making

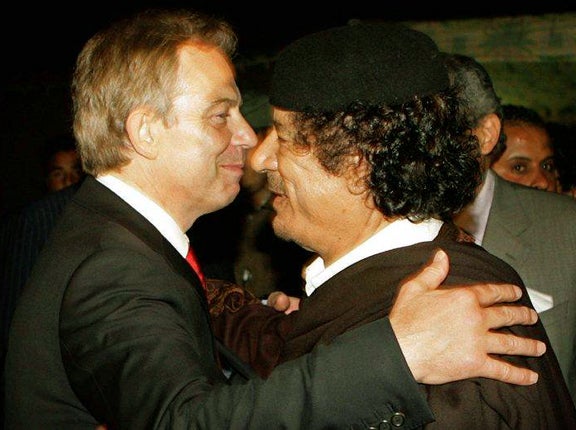

It is shocking to think how recently, and how obsequiously, the Butcher of Tripoli was being feted in the capitals of Europe. Barely six months ago he was corralling the beauties of Rome into the Libyan embassy and trying to browbeat them into converting to Islam. Three years earlier he was being embraced, literally, by Tony Blair and President Nicolas Sarkozy. And the scandal of Megrahi's return is still fresh in the memory. Britain, as David Cameron put it yesterday in Kuwait, "faced a choice between our interests and our values". And it didn't take us long to decide which was more pressing.

But the Libyan vacuum into which we are now peering – trying to envisage what might come after Gaddafi – helps explain why, once he had agreed to drop his laughable efforts to construct a nuclear deterrent, Europe's leaders were prepared to trade what remained of their dignity for a slice of the Libyan pie. For more than 40 years he ensured by brutal repression and oil-based bribery that l'état, c'est moi. Nobody else got a look in.

Here was a "highly controlling regime" – to use Mr Cameron's euphemistic phrase – that was also high maintenance. Either you humoured Colonel Gaddafi's innumerable whims – his terror of long-distance flights, his buxom Ukrainian mistress, his insistence on camels and tents – or you could forget about Libya. And for the oil and gas, we kept him happy.

The same sort of "hollowing" process that happened in Egypt under Hosni Mubarak was far more devastating in Libya under Colonel Gaddafi because there was less to hollow in this thinly populated desert where nomadic traditions are only a generation or two in the past. There was no state to take apart. Colonel Gaddafi claimed to have taken Libyan beyond tribalism, while boasting of his own Bedouin blood. But strip away the trashy impediments of oil wealth, the highways and concrete, and tribal ways and tribal loyalties are still there, just below the surface.

Colonel Gaddafi did a good job of presenting himself as the omnipotent tyrant, the Muslim Mao. But his position was always more precarious than those of his autocratic neighbours in Tunis and Cairo, despite appearances to the contrary. He surrounded himself with members of his Qathathfa tribe and made sure they staffed the elite military units – but the tribe itself was dwarfed in size by others such as the Wafalla, which numbers around one million out of Libya's population of six million.

To neutralise threats, Colonel Gaddafi became a master of divide and rule, bribing the Wafalla to stay loyal while ensuring that other tribes and ethnicities were at daggers drawn with each other. He kept the army weak, abolishing all ranks higher than his own rank of Colonel and bolstering it with African and other mercenaries; when he bombed an Islamist uprising into extinction in the 1990s, it was widely believed that the pilots were Serbian mercenaries.

At the same time, he built up brutal paramilitary forces and recruited a spying network of formidable size and prominence even by Middle Eastern standards. You could not walk down a street in Tripoli without remarking on the amazing number of young men with nothing better to do than lean against walls and gaze around.

The idea, fostered in particular by Tony Blair, that this was a man with whom we could do business exposed the particular brand of hope over expectations that the Gaddafi Show encouraged in our more superficial leaders. How the notion of an ethical foreign policy could co-exist with the idea of throwing down the welcome mat to this monster is one of the scandals of the age.

Long-term watchers of Colonel Gaddafi remember the way he toyed with sub-Saharan Africa, championing the notion of Africa United – while his own citizens treated the Africans on their doorstep worse than dirt. They will remember how he winked at the mass trafficking of migrants from his coast to Italy, to put pressure on Silvio Berlusconi's government to sign a generous deal of wartime reparations – and once it was signed he threw the would-be migrants into his vile jails, to the satisfaction of xenophobic Italians. They will remember how he allowed absurd charges to be levelled against a group of Bulgarian nurses in the country and kept the case going for years until he had extracted a sufficiently huge European bribe to let them go. He has behaved, in other words, exactly like a mafia boss. He played us like patsies for years. And because of the oil and gas, we let him.

He has ensured over many years – by driving all possible opponents into exile and keeping the intellectual life of the nation subordinate to his will – that the only alternative to him was a gaping hole. That is the hole we are now staring into. The intellectual and business strengths of Egyptians and their great national pride lead one to hope that some sort of democratic transformation can occur there. In Libya, such hopes are as flimsy as the hopes of Mr Blair that Colonel Gaddafi would behave like a gent.

What's happening around the region

Bahrain

Tens of thousands of red-and-white draped, flag-waving protesters flooded the capital, Manama, in a show of force against the monarchy. The King promised to release an unspecified number of political prisoners. "Egypt, Tunisia, are we any different?" marchers chanted, calling for the fall of the Sunni rulers they accuse of discriminating against the island's Shia majority. Helicopters hovered overhead but security forces offered no resistance after opening fire on protesters last week, and the size of the event rivalled any of the demonstrations so far in the eight-day uprising. AP

Iran

Two Iranian naval ships passed through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean heading for Syria in a move that Israel condemned as a "provocation". Iran appears to be testing the state of affairs in the Middle East. Reuters

Yemen

Thousands of protesters rallied across Yemen, burning a car belonging to supporters of President Ali Abdullah Saleh in the capital, Sana'a, and chanting for his ousting. Mr Saleh has said that he will step down in 2013. AP

Algeria

Algeria's cabinet adopted an order to lift the 19-year-old state of emergency, a concession designed to pre-empt protests. The measure will come into force from its "imminent" publication in the official gazette, the APS news agency reported. Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks