Vanora Bennett: A tale of brotherly love: When siblings fall out, and try to make up

With younger brother Ed at the wheel, can David remain at his side? Our writer looks at ways siblings have stuck together over the years

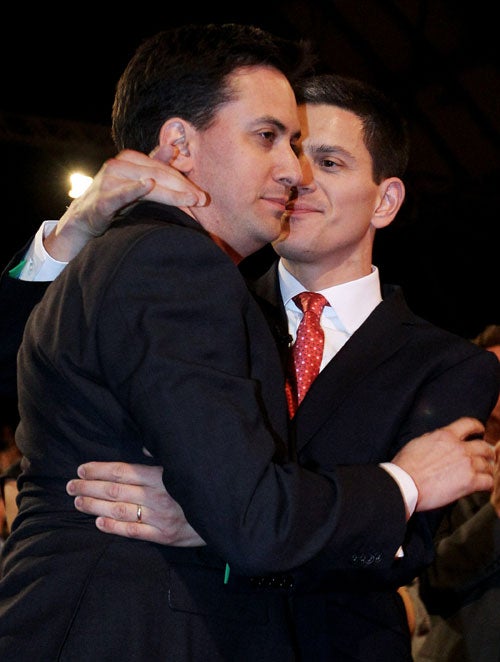

At last we know which Miliband brother has come out top. But the question that has dogged them both throughout the four-month campaign for the Labour leadership – how they'll handle the bitter sibling rivalry that, for all their denials, we know must be seething under those apparently debonair exteriors – still remains to be answered.

History doesn't have many good precedents for David and Ed. Ever since Cain got jealous that his younger brother Abel was preferred by God – with deadly consequences – siblings whose lifelong, usually suppressed, family competitiveness has broken out into open conflict have found it all but impossible to mend their quarrel and come to an accommodation.

Back in the 12th century, the hatreds between Henry II's sons caused a bloody rebellion against the eldest, Richard the Lionheart, by the youngest, later known as Bad King John, as well as subsequent years of war in England's French territories between John and the son of another sibling, Geoffrey.

And what but the most tormented sibling feeling can have prompted Shakespeare's hunchbacked wicked uncle, Richard III, on usurping the throne of England from his young nephew, Edward V (the prince in the Tower, whom he declared a bastard), to go one gratuitous step further and announce that little Edward's father – Richard's own apparently adored elder brother, the recently dead King Edward IV – had also been illegitimate and therefore unfit to rule?

We've almost all experienced the complex sibling dynamic at first hand, since 82 per cent of people in Western countries have at least one sibling, and, according to Jane Mersky Leder, the author of "Adult Sibling Rivalry" in Psychology Today, about one-third of adults describe their relationship with their siblings as competitive or distant.

It's widely accepted among shrinks that child siblings will naturally compete, sometimes aggressively, for parental affection. The American child psychologist Dr Sylvia Rimm says rivalry is particularly intense when children (Milibands take note) are close in age and of the same gender. David Levy, who introduced the term "sibling rivalry" in 1941, believed that, for an older sibling feeling its parents' affection usurped by the arrival of a younger one, "the aggressive response to the baby is so typical that it is safe to say it is a common feature of family life".

It's when this maelstrom of emotion re-emerges in adulthood, however, that trouble begins. The merest scratch at the surface of a few present-day feuds between famous siblings shows how insoluble they are, even if they arise out of something more nebulous than a Miliband-style official public battle for a measurable first place.

Two of Sigmund Freud's grandsons, Clement and Lucian, refused to speak for decades. No one really knows what set the writer, broadcaster and sometime Liberal MP, Clement against his artist brother, but one version has it that the original falling-out was over which of them should have won a boyhood race. Clement is said to have been leading the sprint through a public park, only for Lucian to call out, "Stop, thief!" A passer-by apprehended Clement, and Lucian legged it to the finish. Lifelong estrangement followed. In 2008, Lucian refused to go to Clement's funeral.

The Miliband brothers are well aware of the risks to which their recent public competition has exposed their personal relationship. Ever since they declared, back in May, they've been at pains to stress their strong family unity and fraternal love, and play down any personal rivalry.

This was easier to believe at the start of the campaign, when it looked as though the more politically experienced elder brother was in any case the voters' runaway favourite.

This seemed emotionally right – a kind of natural justice. History has favoured elder sons going first ever since the days when interrupting the flow of power from father to oldest son could bring about full-scale war. Richard the Lionheart may have provoked his little brother's rebellion by refusing to give John the territories their father had earmarked for him, but it's still Richard, rather than John, who's remembered with affection.

Things are, however, bound to get trickier all round if it's the younger brother who gets ahead of his older sibling, even though the older one will have been raised in the expectation he'll go first, and may also always (as one sometimes senses with the Milibands) have slightly patronised the aspiring mini-me trotting breathlessly along behind. And it was to this more uncertain terrain that the Labour contest moved as the summer drew on, with the bookies putting Ed a hair's breadth (11-10) ahead of David (10-11) by Friday.

Our ancestors would have seen any such advance by the younger brother as usurpation in the offing – an abuse of the natural order of things. You only have to read The Tempest to see what Shakespeare thought of the "unnatural" behaviour of Antonio, who stole his brother Prospero's dukedom, but got his come-uppance after being shipwrecked on the very island that the dispossessed Prospero had been consigned to. History only offers one ending to this story: whenever little bro gets his hands on power ahead of his time, it ends in tears.

And, even though the guiding principle of governance nowadays is different – that the best man for the job should get it – we still seem to feel this twist in the brothers' fates with the pain our forebears did.

The determinedly non-confrontational Milibands, apparently understanding this, tried to take the poison from the sting of Ed's rise. On Friday, David made plain that he'd swallow his pride if he lost – and work for Ed.

This suggests to me that the Milibands are – rather late in the day – taking a leaf from the book of modern America's two most successful political clans. Both the Bush and Kennedy families have successfully harnessed the natural rivalry of brothers, keeping family relationships on an even keel even as several siblings at a time become big-league politicians.Their example is probably the best template for David and Ed to follow as they absorb the psychological impact of the leadership result, if, as they say, they want an accommodation now.

Item one in the template is a family myth of past political glory that binds the sons together in a desire to continue the tradition. JFK and Bobby Kennedy looked up to hero-daddy Joe Snr, ambassador to Britain until 1940. The Bush brothers of our time, George W and Jeb, had the achievements of their presidential father, George H W, to emulate.

The Milibands have that heroic, unifying myth. Their father Ralph was a giant of the left. Both he, and their mother, Marion, fled the Nazis and established successful lives here.

Lesson two for emulation is a willingness to submerge individual ambition for the greater good of the family. Both American families achieved this by making sure that siblings took their turn at power in the family pecking order – oldest first. Bobby Kennedy only ran for president after JFK's assassination. Likewise, on the say-so of the Bush family matriarch, Barbara, Dubya, the drinker, got the first go at the presidency, rather than the more obviously able, though younger, Jeb.

The Milibands have gone astray on that. But they could yet put things right between themselves by adhering to the Bush/Kennedy lesson three: the big-up for the one waiting in the wings. For this weekend's loser David to maximise his chances of getting the big job later, he must become his brother's loyal lieutenant now. Ed likewise, must keep his brother in the public eye, with a high-profile job and regular public praise.

JFK did this for Bobby, who served as his elder brother's attorney general. Jeb Bush, who patiently sat out his brother's presidency as governor of Florida, was showered with public praise by George W, and is now being mooted – by, among others, his father – as a good man for the US presidency. It's the same system that's worked so well elsewhere for, among others, the Castros, the Gandhis and the Bhuttos.

We don't yet know what job David Miliband might accept from Ed if, after absorbing this result, they find they can work together.

But I can see one big snag in any political happy-families scenario. And it's this. Democracy isn't supposed to be about dynasties.

If voters have expressed a preference for one strand of political thinking over another, they will be disconcerted if their choice is disregarded in the interests of mending a Miliband family rift.

I'll be sorry if the brothers' relationship suffers and one's career implodes. Yet, in the interests of good governance, I can't help thinking that it might be best for the rest of us if they don't sort things out between themselves too cosily, too soon.

Fraternal friction among the famous

Sir Jack and Sir Bobby Charlton Footballers

Famously embraced each other when England won the World Cup in 1966, but in 1996 Jack, the elder by two years, expressed his anger at Bobby for not visiting their mother, Cissie, before she died: "I just don't want to know him." A decade later Bobby, whose wife Norma had clashed with his mother, said: "If I see him, I speak to him. I'm not going to ruin the rest of my life worrying about my brother and I've no doubt he's the same." They settled their differences in December 2008 when Jack presented Bobby with the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award, the latter pronouncing himself "knocked out".

Noel and Liam Gallagher Founders 0f Oasis

Liam, the cocksure front man, never stopped resenting the perception that he was merely the instrument of his brother's songwriting talent. Noel complained about his brother's brattishness: "He's rude, arrogant, intimidating and lazy." It was bound to come to blows. Last August, Noel quit the band, saying: "I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer."

Jonathan and David Dimbleby Broadcasters

Are, like their father, Richard, driven by competition. Jonathan is always trying to steal a march, professionally, on his elder brother, although they don't slag each other off publicly. The elder has the TV kudos of Question Time; his sibling gets the consolation prize of Radio 4's Any Questions. Election night is the key battleground. In 1997, when Dimbleby J made his debut as ITN's election-night host, Dimbleby D, the BBC's anchor, said: "My instinct will be what it always is, to smash ITV into the ground and grind them under my heel." With viewing figures of eight million against ITV's five – he did.

Ralph and Joseph Fiennes Actors

Profess to be the best of friends, but the CV of Ralph, the elder by eight years, is more impressive: The Hurt Locker, Schindler's List, The English Patient, Lord Voldemort in Harry Potter and two Oscar nominations. Joseph – Shakespeare in Love – seems irked by talk of competition: "I wasn't really inspired by him. It was something totally in me." And "I'm fortunate to have advice from someone of that calibre. He's years older, so there's no danger of us going for the same roles."

Vanora Bennett's latest historical novel, The People's Queen, was published by HarperCollins in August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks