Why cricket forced batsmen to give up scientific advances

Technological innovations in bats have hugely altered the balance between batsmen and bowlers, which makes the authorities' action this week long overdue, writes Angus Fraser

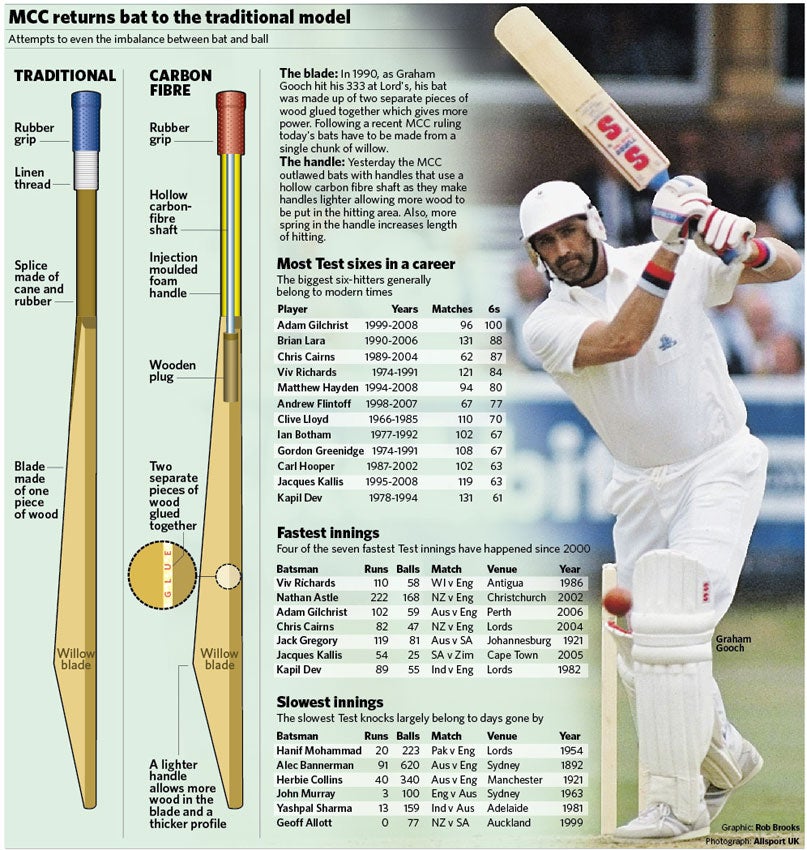

Remember the bat Graham Gooch used when he amassed 333 against India at Lord's in 1990, the highest Test score posted at the home of cricket? It was a Stuart Surridge Turbo and the deliveries sent down by Kapil Dev, Manoj Prabhakar and Ravi Shastri pinged off its face and raced to the boundary with unerring regularity, even when it failed to hit the middle of the blade. The score will for ever remain on the honours board in the home dressing room at Lord's, but the laminated bat has since been banned.

Cricket administrators, like those in all sports, are attempting to come to terms with technological progress, whether it be through using television replays to aid the decision making of umpires or the kit the players use. In most areas the game is happy to embrace the advances. The number of decisions referred to a third umpire sat in a booth at the back of a stand is only likely to increase, and the clothing England's players will sport this summer is lighter, more comfortable and more effective than any worn before. It removes sweat from the surface of the body and transports it to the outside of the garment, where it evaporates.

Yet progress is not being happily embraced where the balance between bat and ball is potentially compromised. One major concern is the bat, the most important piece of equipment in the game. Bats have changed enormously in the last 30 years, as can be seen by a visit to the museum at Lord's. On show are pieces of willow used by W G Grace in the late 1800s, Jack Hobbs in the 1920s, Brian Lara when he struck 375 in 1994, all the way through to the modern day.

The transformation is amazing. Gone are the thin little 2lb 3oz blades used by batsmen such as Don Bradman. Players of his generation relied on touch, dexterity and placement to score runs. The unpredictability of uncovered pitches meant that skill levels were high, with a light tool being easier to handle. Cricket continues to change and it is fast becoming a power game played by big, strong men wielding big, heavy bats that effortlessly clout the ball over the advertising boards and into the stands. Batsmen are no longer worried about placing the ball between fielders; they now look to hit it through or over them. And, with the ever-growing prominence of Twenty20 cricket, the trend is only set to grow.

And this is where the problem lies. The balance between bat and ball is fundamental to the game. Inevitably, there will be times when conditions allow batsmen to have a better time of it than bowlers, and vice versa, but it is not in the interests of the game for one component to dominate the other totally. It is meant to be an even contest.

Golf has similar problems, although they do not concern one element suffering a disadvantage. Modern clubs and balls are reducing many of the world's greatest courses to nothing more than a pitch and putt, and in an effort to keep up with technology and preserve relatively high scores the game's administrators are having to amend courses. Holes are being lengthened and the layout changed by placing bunkers and water hazards in unfavourable positions.

Cricket does not have such luxuries. Most grounds are arenas and the size of boundaries is limited by the presence of stands – not that this prevents groundsmen reducing boundaries to the minimum distance of 70 yards, in the belief that fours and sixes provide greater entertainment. And people wonder why there are very few quality spinners in the game.

Knocking down grounds and starting again is not an option. Most are in urban areas, surrounded by houses and roads. It means the distance a ball can be struck has to be controlled. Substances are available that could see mishits comfortably disappear over the longest boundaries, so governance, which is the responsibility of the Marylebone Cricket Club, needs to be vigilant if the game is to be prevented from becoming a joke.

Kevin Pietersen has developed a new party trick using a wooden bat that has a rubber compound cut in to its blade. The bat makes it easier for England's coaching staff to hit high catches during practice using just one hand. At each venue he plays at with England Pietersen goes into the middle of the ground and attempts to hit a ball out of the stadium. The tall stands at Lord's may test him, but he succeeded on each occasion during the winter.

The bat market is extremely competitive, with manufacturers desperately trying to convince children and amateurs that theirs is the blade to use. Each is attempting to outdo the other, with the aim being to provide batsmen with the largest sweet spot – the area where energy transference is at its most efficient – possible. Some of the creations are nothing more than gimmickry, but others have made a real difference. The bat Gooch used in 1990 worked because it was made of two pieces of willow joined together. The presence of two pieces of wood stuck together with glue reduced flex when ball came into contact with willow, increasing the transfer of energy and giving the batsman a clear advantage.

It was the same with a Kookaburra bat used by the Australia captain, Ricky Ponting, two years ago. The Kahuna had a black carbon fibre back to it, breaking Law 6, which defines that a bat should be made solely of wood. Like Dennis Lillee, who briefly used an aluminium bat in an Ashes Test in 1979, it was subsequently banned. Another contentious issue is corking, a process whereby holes are drilled into the back or bottom of a bat before being filled with cork, and which is banned in baseball. The benefits were deemed to be twofold, in that it reduced the weight of the implement and increased its trampoline qualities.

With the law referring to the blade of bats being tightened, manufacturers turned their attention to handles. It did not take long for a carbon fibre shaft surrounded by foam to appear on the scene, a development that immediately caught the eye of the MCC. Though revolutionary, the innovation, like those made to blades, ended up on the scrap heap following yesterday's decision by the MCC, which stated that handles must be made of cane (bamboo), rubber – to reduce vibrations – glue, twine and rubber grips.

Despite these restrictions, bats are still far better than they were. Even blockers like Michael Atherton would have benefited from using the bats Pietersen plays with. "I have got one of Atherton's old bats," said the England captain, Michael Vaughan, "and if he was around today using the bats that are available to us he would be averaging in the mid-40s rather than 39." The downside of Vaughan's assessment is that most of England's batting line-up, who take pride in telling everyone that they average over 40, would only be averaging in the high thirties if they were playing a decade or so ago.

The main difference between bats of 50 years ago and now is that modern bats are not pressed as hard and are therefore not as thick. Pressing made them harder and less likely to break, but players are no longer worried about wastage. Players of the past were limited to two or three bats a season; now they get as many as they want.

There are several reasons why players want thicker bats. One is visual – they feel more confident about hitting the ball over the top when they look down and see a large chunk of wood there. Thicker edges mean that the margin of error on a mishit is greater too. But the main reason is that an unpressed bat, where the wood particles are not pressed so close together, seems to have a springier feel to it. The trampoline qualities of it appear to increase, meaning that the ball can be hit huge distances with flicks rather than full-blooded heaves.

Gooch's bat now sits in a display cabinet with a painting of the old Grandstand scoreboard at Lord's by Jack Russell, the former England wicketkeeper, on its blade.

For those fearing that technology is about to create a breed of superbats, it is heartening to know that Gooch's is now a work of art.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks