Johnny Herbert on Le Mans 24 Hours success, proving his doubters wrong and why drivers shouldn't rely on noodles

Herbert recovered from a horrific accident at Brands Hatch in 1988 to win the Le Mans 24 Hours in one of motorsport's Great Fightbacks

It takes a special mentality to come back from the brink when others have written you off, but to do it on the most testing stage of them all, a 24 hour race against the best drivers on the planet in some of the fastest sportscars available, takes something extraordinary.

After a shocking Formula 3000 accident at Brands Hatch in 1988 that nearly led to the amputation of his left foot, Johnny Herbert embarked on a Formula One career clouded in uncertainty – was he the same racer, could he pushed a car to its limit and would there be lasting effects from the extensive injuries the British driver suffered?

Some answers would come in Herbert’s F1 debut, when he defied the odds to finish fourth at the Brazilian Grand Prix in Rio de Janeiro in 1989. But Herbert would go on to prove his credentials – and then some – when he crossed the line on the famous Circuit de la Sarthe to give Mazda their first and to date only victory in the Le Mans 24 Hours.

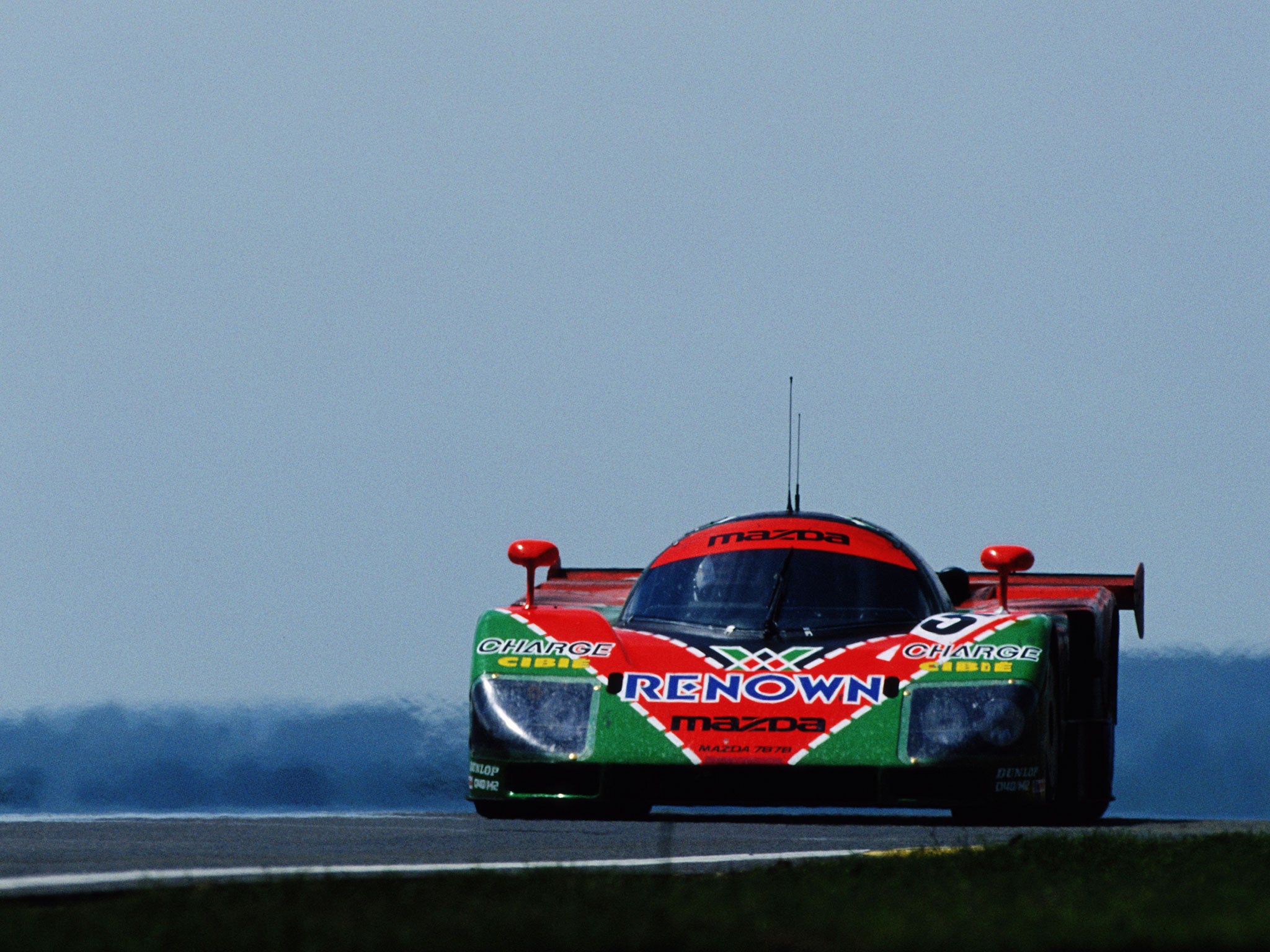

Herbert’s story is being documented by the tyre manufacturer that carried his Mazda 787B to victory 25 years ago, Dunlop, as they recount 10 of the Greatest Fightbacks seen on the track. Joined by German Volker Weidler and Frenchman Bertrand Gachot, Herbert overcame the challenge posed by the faster Sauber Mercedes C11’s and Tom Walkinshaw-run Jaguars XJR-12’s, but it was his own personal comeback that puts the achievement up there with other names such as Jackie Stewart, Mike Hailwood and John McGuinness, which can be viewed in the gallery below.

“After the accident in 1988, Le Mans was almost a stepping stone for me to prove to other people in Formula One, and probably out of Formula One, that my injuries were really not an issue and that is really the biggest and toughest race that you can go and prove that,” Herbert tells The Independent.

“What I remember, at the beginning of the race to the end of the race, we never eased off even when we were leading, even with maybe 20 minutes to go. We still had the Jaguar following us behind because they were in second and third and you had to be aware that with Tom Walkinshaw running that Jaguar outfit at the time that you couldn’t allow that Jag to get close to you because you never know what they might try, so you have a whole 24 hours of basically different experiences merging into one.”

Should a driver go about trying to prove they can still mix it at the top, it would be ill-advised to tackle Le Mans in order to do so. Yet it was Herbert that remained in the Mazda beyond his final stint to take it to the finish line and, to this date, give a Japanese manufacturer victory in the historic race. It took its toll on Herbert though, as he was unable to take to the podium after collapsing from a combination of dehydration and malnourishment shortly after taking the chequered flag.

“Unfortunately the only experience that I missed – and I still don’t know to this day if I’m the only one not to make it – is the podium,” he explains. “But even at school I was always after attention so that’s one way of getting it I suppose!

Herbert adds: “There were reasons for that. In Formula One it wasn’t such a big problem. I was a bit like Nigel Mansell, I tried muesli, I tried bananas, I tried all that sort of stuff. It never helped my stomach when I felt like I wanted to be sick, so a fry-up was something that was a lot better. But being in a Japanese team, fry-up and Japan - they don’t get on very well.

“So the only thing I survived on – although effectively I nearly didn’t because I keeled over at the end of it – was Pot Noodles, which have got no nourishment or goodness in them whatsoever.

“I was only meant to do a double stint and then I was out and Volker would get back in the car. But because we were in the lead, everything was going so well and we were consistent, they asked ‘are you ok to stay in the car to the end of the race?’ and I think there was maybe another stint-and-a-half remaining, and typically being a racing driver you want to drive across the line at 4 o’clock and win one of the biggest races at that point in your career. So I stayed in the car but of course had no fluid, no noodles, and my body ran out of puff after the race.

“But it didn’t matter because my concentration was there throughout the race, I got across that 4 o’clock line and we had won the 24 Hours of Le Mans. It would have been lovely to get up onto the podium but I can still look back at it today with a lot of happiness that eventually we did achieve a pretty might win because it was unexpected, the little Mazdaspeed car with a rotary engine – a very noisy one at that – and it’s still the only Japanese victory at Le Mans today which Nissan and Toyota have tried many times. That’s something quite nice to look back at, that that victory today still hasn’t been broken.”

To read Herbert’s full story as well as Dunlop’s nine other Great Fightbacks, click here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks