Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School: Why Britain's education system should embrace China's teaching methods

Three British headmasters share their views on the teaching methods being used by Chinese teachers in the BBC2 documentary

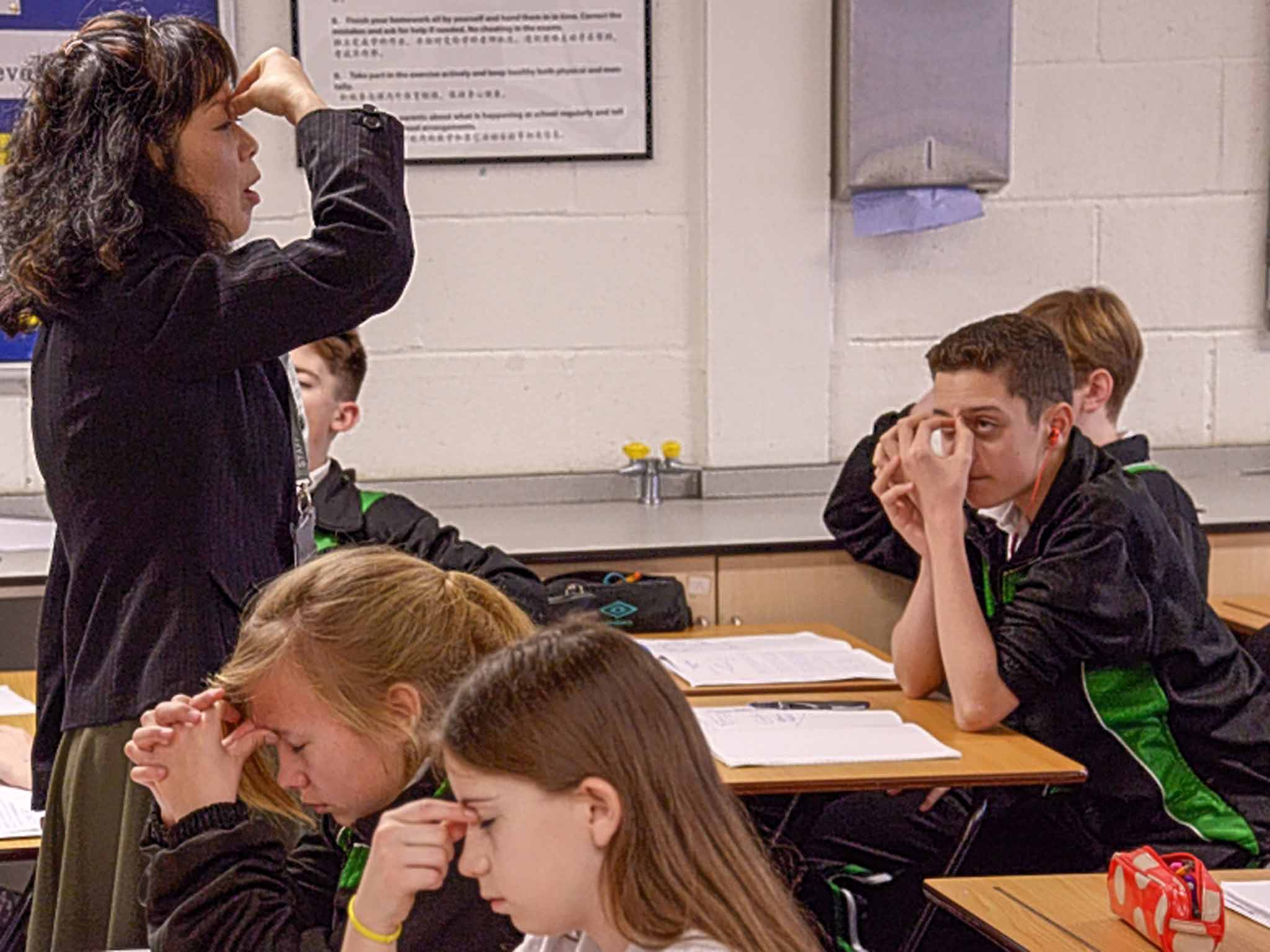

As we approach tonight’s second episode in the three-part BBC2 documentary Are Our Kids Tough Enough?, viewers are prepared to see the dynamic between the five Chinese teachers and their 50 British students deteriorate further.

The public seem to have begun turning against the Chinese teaching methodology after last week’s episode, which has been implemented as a four-week experiment in Bohunt School, Liphook. It enforces 12-hour days and discipline that aims to ‘embarrass’ students into behaving.

Headmaster of Bohunt School, Neil Strowger, reacted angrily to the way his school was made to appear as if it had disciplinary problems, blaming the Chinese methodology for being “mind-numbingly boring.” Bohunt School is, in fact, a successful state school, rated Outstanding by Ofsted.

The documentary has sparked many defensive comments which aim to disparage Chinese teaching methods in what seems to be a rather uninspiring and binary battle of ‘who’s better?’ Viewers have criticised the Chinese methods for being robotic, following the ‘chalk and talk’ teaching style where students mechanically copy notes.

Mr Strowger – who called this teaching style “lazy” – added: “Now to my mind, that’s not an education.”

The Chinese teachers were just as shocked by the behaviour of the British pupils. They pin-pointed pupils’ lack of ambition, and one suggested: “If the British Government were to cut benefits, children might study harder as a ‘ticket to a better life’.”

Richard Cairns, headmaster of Brighton College – where Mandarin is compulsory from the age of 11 – says he is not surprised by this friction and adds: “We have often found that teachers recruited straight from China find our pupils to be a challenge. There is a cultural disconnect. Chinese teachers expect their pupils to listen, absorb, and regurgitate. British teachers expect their pupils to learn as much through interaction as instruction.”

However, Mr Cairns does not believe these cultural differences to be harmful, and says: “Debate and discussion in class are thus seen as positive things, not threats, to good order.”

He concludes the binary comparison between Eastern and Western teaching methods is irrelevant to improving schools across the UK: “The best schools in England, of course, will have teachers who can educate pupils by both instruction and interaction.”

Instead of hitting-back with the self-indulgent defence line of ‘our school’s better’, headmaster Mr Strowger might benefit from a less binary approach. A simultaneous understanding of what is and what isn’t working with the Chinese methods would surely lead to a more fruitful experience than immediately erecting a barrier.

Anthony Seldon, departing master of Wellington College, says he believes “the whole debate goes wrong when we talk about it being either/or.”

This immature either/or argument is beneath the Chinese, however, to whom a British education is very much sought after. Unlike the British – who seem so defensive in the face of an ‘alien’ teaching system that might shine an uncomfortable and unsparing light on some of their weaknesses – the Chinese are readily welcoming British teaching influences.

Both Wellington and Brighton Colleges have links with China. Mr Seldon opened-up a school in Tianjin in 2011 and Shanghai in 2014 – with further plans to open a third outpost in China – and Brighton College plans to open its own school in Bangkok next year. The school will follow a UK curriculum and replicate Brighton College’s core values.

Yet, across the globe, why do the British slam their doors shut at the prospect of needing help from abroad? Surely refusing to recognise weakness is far more humiliating than accepting help? If we look at PISA and OECD data, eastern countries, including China, rank amongst the top schools in the world.

Chinese students’ achievements were highlighted in the BBC2 documentary as being three years ahead of British students. To try and deny that China is doing something right would be pointless.

Mr Seldon disapproves of Britain’s ‘insularity’, which has become so apparent following last week’s episode, and hopes we will be able to learn from China’s focus on discipline, rigour, and intensity. He says: “We have huge amounts to learn from China. We need to congratulate the Chinese on their openness.”

Instead of pitting the East and West against each other in this black and white battle for superior teaching methods, perhaps we should share in the excitement of the headmaster of University College School, Mark Beard.

Speaking of the prospect of the East and West coming together, Mr Beard says: “If the best of the East and the best of the West collaborate over teaching and learning methods, then perhaps this will pave a way for all children to enjoy an ever more powerful education.”

Mr Seldon emphatically adds: “You can’t fly with only one wing. You have to have both.” So, what’s stopping China and Britain from forming two wings and taking flight together?

Twitter: @elliehalls1

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks