Cameron is adept at the art of apology, so why doesn't he give one to India?

Many Indians feel that Britain's outrages during the colonial era have never been fully admitted, never mind taken responsibility for

David Cameron really likes apologising for things that aren’t his fault. As children, this is a move many of us deployed in underhand efforts to win familial arguments, and I can see why he likes it. Whether over Christmas dinner or in the House of Commons, it’s a perfect rhetorical gesture: you get to look statesmanlike, soothing, compassionate, and open-minded at the same time as surreptitiously laying the blame at someone else’s door.

Consider his statement on Bloody Sunday – admirable and necessary, certainly, but no less effective a piece of politics for that, and featuring the conspicuous observation that for someone of his generation, that era was something “learned about rather than lived through”. That speech won near-universal plaudits; for the Prime Minister, there was no significant downside. There are few meaningful decisions he will take in office that could carry that label, and when they come along, it’s unsurprising that he would jump at them without hesitation.

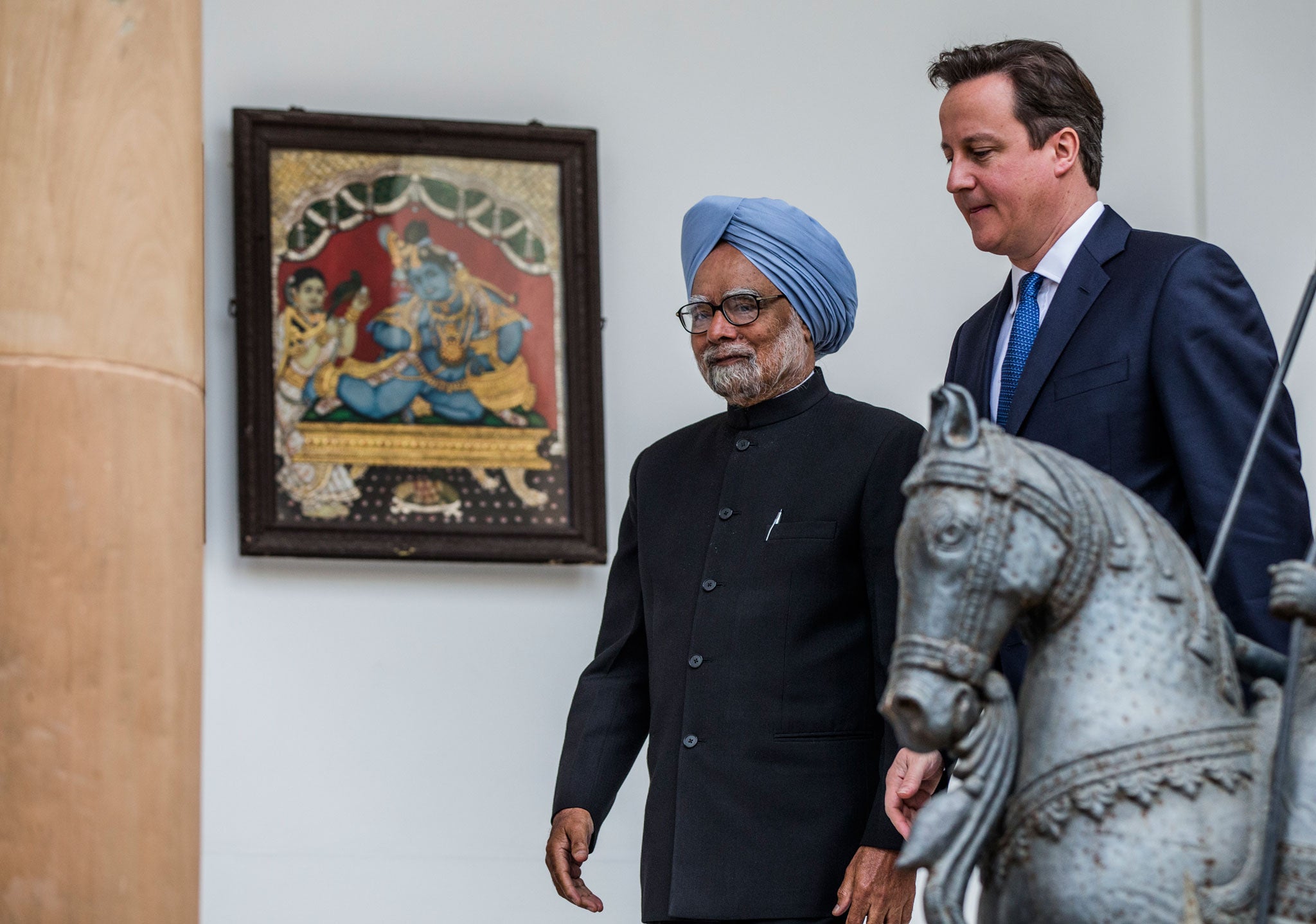

He won’t do it in India today, though, despite what looks like an open goal of an opportunity to do so. Many Indians feel, with obvious justification, that they are owed an apology for some of the outrages of the colonial era, not least the Amritsar massacre of 1919, where at least 400 peaceful protesters died; meanwhile, Cameron is trying embarrassingly hard to win favour with a global economic player. The rationale, both political and humanitarian, seems clear. But while the Prime Minister will express his regrets, he will stop short of an apology: the kind of semantic distinction that seems utterly irrelevant in real life, and even in politics, until someone is willing to articulate one and not the other.

The depths of the realpolitik at work here – and the calculus that deems one massacre in Northern Ireland worth saying sorry for, and another in India not – are beyond me. There is presumably a finely honed diplomatic memo that explains it very clearly. Still, coming the day after Cameron leapt – along with Ed Miliband – so eagerly and unthinkingly on the bandwagon aimed at Hilary Mantel, it does gall a bit. In one instance, a fiercely intelligent and deliberately misunderstood woman has been instantly traduced by our leaders for daring to make a subtle point without undue concern for the political consequences; in another, a country has been kept waiting for an apology that it has been owed for the best part of a hundred years, and this despite the obvious fact that everyone concerned understands quite how profoundly it is needed.

The explanation, I’m afraid, is that one entails an easy political win, the other an unpredictable political headache. But to mean something, an apology has to cost something: in the circumstances, we are entitled to ask whether we can really trust these ‘regrets’ at all. And we might offer David Cameron a modified version of the admonition our parents gave us: don’t apologise if you don’t really mean it. But also, don’t withhold an apology if you really do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks