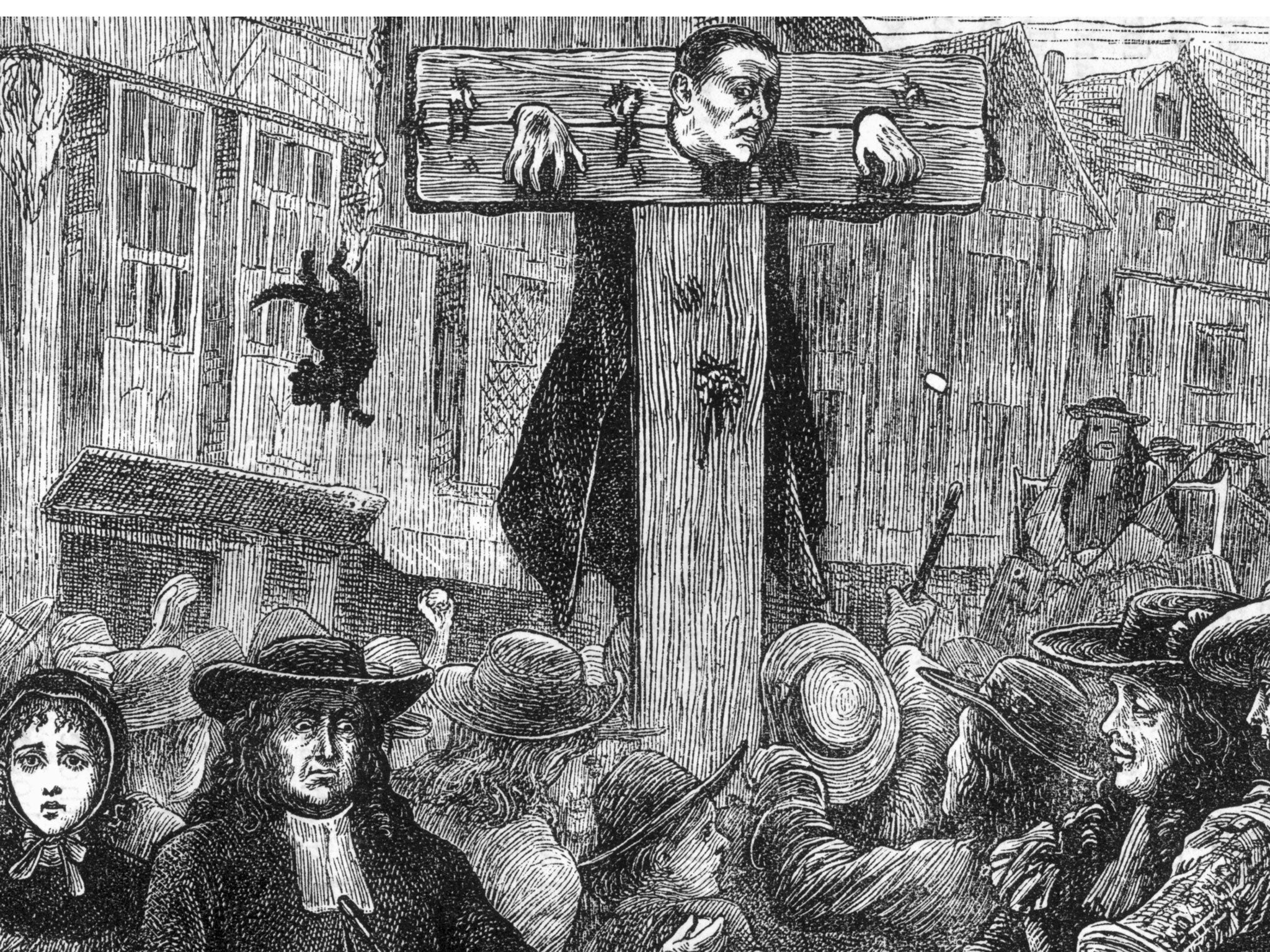

Humiliating, unnecessary, unjust: The criminal record system is the modern equivalent of the stocks

Almost everyone has broken the law at some point, but 'enhanced disclosure' can make the stigma of a criminal record impossible to overcome

An ex of mine once asked why I didn’t consider doing some teaching to supplement my income as a freelance journalist. I told him this could be tricky, given that I have a criminal record. He laughed, thinking I was joking, and it took me some time to convince him that I do indeed have a spent conditional discharge, plus a caution (both for shoplifting when I was a teenager, if you're interested). I think he was a bit shocked – but then, he was a lot more middle class than me, and probably unaware that one in four of the adult British population has a criminal record of some kind.

These crimes of mine would currently show up in an enhanced disclosure required for certain jobs – although maybe not for much longer, thanks to a recent ruling by the High Court, which could see an end to discrimination against those with minor, historic and irrelevant offences on their record.

Put your hands up if you’re a criminal too. Really? Are you sure? You’ve never done any drugs, pinched sweets as a kid or exceeded the speed limit as an adult? The reality is, most of us have broken the law at some stage, and whether or not we end up saddled with a record is more a question of luck – whether we got caught, basically.

For too long, too many decent people have had their career options limited by the enhanced disclosure process, where even convictions which are “spent” under the 1974 Rehabiliatation of Offenders Act are revealed for the purposes of certain jobs. Whilst having a record doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t be employed as, say, a lawyer or a social worker, at the very least it causes unnecessary embarrassment and might create a false impression of someone’s character. In practice, many people don't even apply for jobs where they know their history will come to light, in some cases leading diminished lives and depriving our industries of potentially excellent employees.

Crime is a class issue and always has been. A quick straw poll of my friends, who come from a variety of backgrounds, reveals that while we all admit to misdemeanours, those from working-class backgrounds are more likely to have been dealt with by the courts. Sociologists have many theories as to why this is so, but coming from a “good family”, going to a good school, being aware of your rights when arrested and knowing what to say can all help someone avoid a conviction. So the “chavs” from the estate get a criminal record for their acts of vandalism and drunken fights, whilst the “toffs” in the Bullingdon Club smash up restaurants for fun and end up – er, running the country.

Of course, the laudable aim of enhanced disclosure is to protect children and vulnerable adults from those who would harm them, and few people would argue that serious offences should go undisclosed. But the best criminals are those who never get caught, and many of the worst kinds of offenders leave this world without a stain on their character – the late Sir Jimmy Savile was never even charged with an offence, let alone convicted, during his lifetime. Sexual abuse and rape are the most difficult crimes to detect and to prove – whereas crimes committed mostly by poor people, such as theft and social security fraud, are among the easiest to convict, particularly with advances in technology.

It is hardly surprising that poor people are more likely to steal than affluent people – whilst wealthier people are more likely to commit crimes such as tax evasion and fraud. We used to chop off the hands of sheep stealers or put them in the stocks to humiliate them, and now we force them to eveal their past mistakes, even years after they occurred. I have friends who have overcome difficult upbringings to gain good degrees, only to find themselves worrying that a minor incident from years ago could still hold them back. The present system is akin to Javert in Les Miserables following poor old ex-con Jean Valjean like a stalking horse, roaring in his face, “You’re 24601”!

What we chose to label as criminal reflects the values of our capitalist society, with its emphasis on protecting private property and business above the person. In the UK the average sentence lengths for sexual assault are four months and for theft two and a half months, but there are also numerous individual examples of harsher sentencing for theft, such as during the London Riots, when people received considerably longer sentences.

People often confuse the label of “criminal” with “bad”, but a person considered to be “of good character” in the eyes of the law could be a lying, cheating, adulterous bully with a serious personality disorder. Whether or not someone has a criminal record does not necessarily tell you about their morality and values, and some of the kindest, most sensitive and intelligent people I know have been convicted of something or other.

The current system of enhanced disclosure was introduced by David Blunkett as a knee-jerk reaction to the Soham murders. It has become a costly, cumbersome administrative beast which is having unfortunate consequences for those who pose no more threat to society than most other people.

The Government has said it is “disappointed” with the High Court ruling, but in my opinion, they would be very foolish to oppose it. Instead of blanket disclosure for certain jobs, the charity NACRO has called for a more nuanced system to be introduced, where only truly relevant convictions should be revealed to employers. Of course, we need to know if somebody poses a threat to children or is a prolific fraudster. But we should not really care if they nicked something from Topshop as a daft teenager. Frankly, it’s none of anybody’s business, any more than your medical records or your sexual history. Your past is your past, and let those without sin cast the first stone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks