Labour’s time is right, but do they know it?

The party needs to show that it can reach out to beyond its core vote

The current political circumstances are more benevolent for Labour than they have been for many decades. The right is split, a schism now reflected in pre-election defections from the Conservatives to Ukip. Left-of-centre voters who supported the Liberal Democrats still fume with a sense of betrayal and switch to Labour.

Listen carefully to those who voted Ukip last week and they are crying out for more government intervention rather than less. They want the Government to intervene in the labour and housing markets. They feel powerless in the face of other markets, such as energy. They want an NHS that can be relied on. They ask government to help them rather than leave them behind, a demand that has more in common with Ed Miliband’s agenda than the one espoused by right-wing libertarians in the Ukip leadership.

Listen also to more affluent, urban middle-class voters – especially in London – with whom Ukip has fared poorly. They are fearful too. They turn to government in the hope that it can sort out the nightmare of care for the elderly, rather than being ;left to to a lottery in which they fear they might have to sell their homes to pay for erratic private care.

They worry about their children, struggling in the jobs market and facing high rents. They too are concerned about the NHS. It is laughable to read or hear that when Miliband highlights the NHS or failing markets he pursues a core vote strategy. To revive a New Labour soundbite, these issues touch the many and not the few.

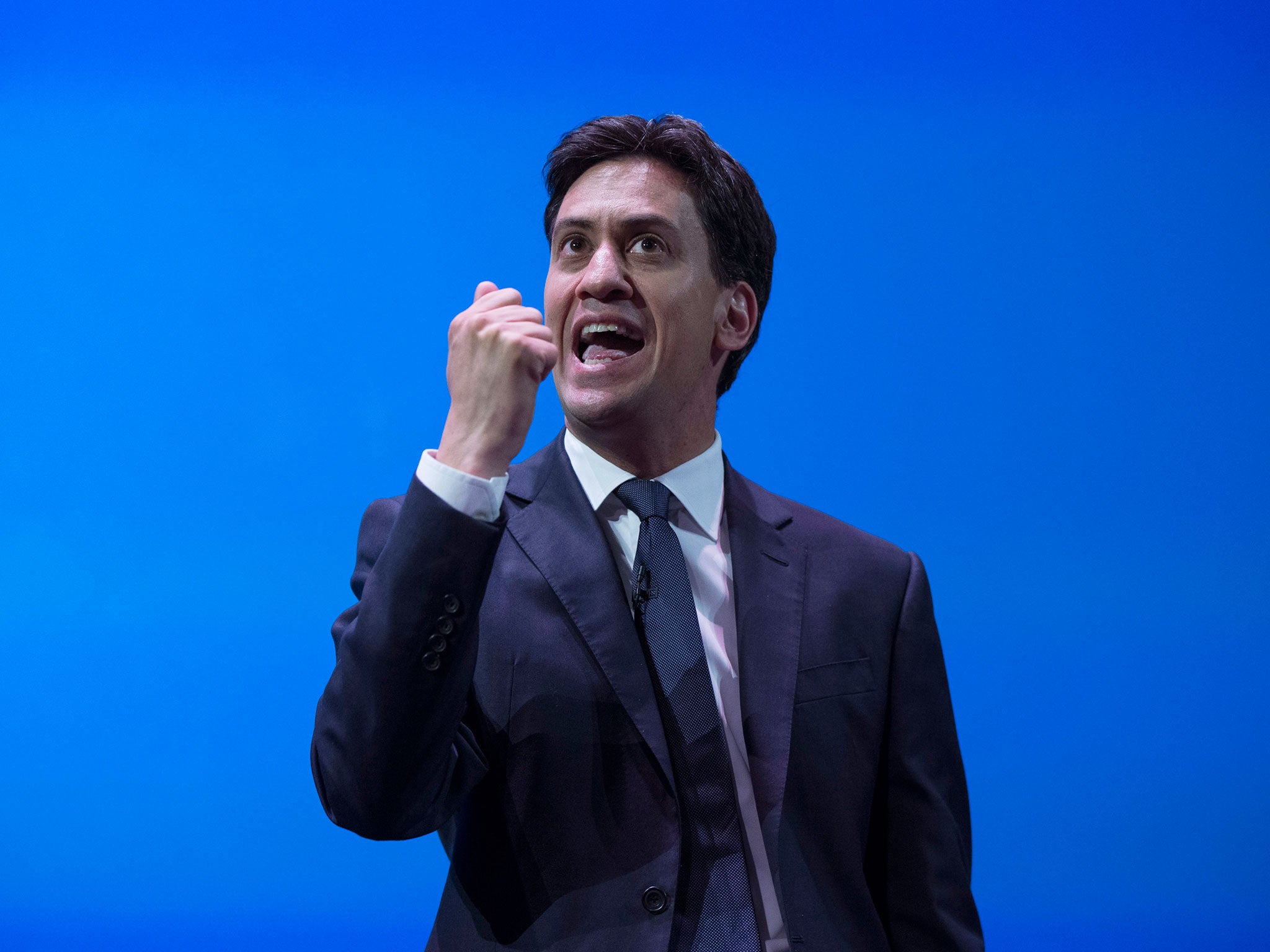

So given this context, why is Labour so agonised and nervy? Part of the answer is that few voters know what Miliband stands for, or if he stands for anything at all. When I was in Scotland for the referendum campaign I heard voters cry out for policies that he espouses, and then heard them dismiss Miliband as being the same as David Cameron. They did not know who he was and had ceased to care.

Nick Clegg’s problem is a failure to explain to those who had voted for his party why he had acted in the way that he did after the 2010 election. There has been no dialogue with his left-of-centre voters, no attempt at persistent explanation. They are very different figures, but like Clegg, Miliband is a young leader who moved to the harsh glare of the centre stage at an early phase of his career, untested by publicly fought battles and with no fully developed public voice.

In Miliband’s case this has led to periods of near-silence. Where is the clear declaration from him, repeatedly made, that issues of genuine concern go well beyond a core vote?

Without such a persistent cry the rest of the electorate will assume they might be losers under Miliband. Where is the explanation that if Labour takes an interventionist approach in relation to immigration it is not an aberration but wholly in line with its view that the state has a duty to intervene in some markets?

Yvette Cooper made this point well in her party conference speech – that a balanced approach to immigration is more logical for Labour than the free-market, libertarian right.

The argument needs to be made daily, with the admission that the previous Labour government got it wrong. The issue is complex, and to appear anti-immigration would lead to deserved defeat. But to repeat the argument endlessly, accessibly, that managing immigration is a left-of-centre issue should not be beyond the wit of a self-confident, clear-sighted leadership.

The frustration with Miliband’s conference speech last month was that, as usual with him, he seized on a potent theme, arguing that the UK is better together rather than living as a bunch of atomised individuals at the whim of wild markets, unprotected by a shrinking state.But he failed to develop the argument. Equally disastrously, he got into an unnecessary bind over the deficit.

Miliband has got a sense of proportion over the deficit. He knows how George Osborne exaggerates its significance, the Chancellor having failed to wipe it out. Yet because Miliband forgot to mention it, and explained in endless interviews how he made the omission, he ended up talking only about the deficit and will now have to do so repeatedly to show that he appreciates the seriousness of economic policy.

One ally suggests that some of the anecdotal episodes in the speech were included on the advice of his US-based advisers: “Use real people… show that you are in touch…” If that is the case, Miliband should pay less attention to those so far removed from a UK election.

Although Miliband is more alert to fundamentally changing times than other leaders, he sometimes behaves as if it is still 1997. The challenge then was to show that Labour was rigidly united and economically competent.

The New Labour control-freakery is still in place, so much so speakers at this year’s conference were scared of uttering an interesting word, their every comma checked with the leader’s office, even if some of those in that office might be ill-equipped to judge whether cautious banality is the most effective path to victory.

On this the Tories are well ahead, capable of staging lively, grown-up debates without damaging each other. There is also a temptation, as far as Miliband and Ed Balls are concerned, to play the New Labour trick of using small symbolic policies to illustrate a broader sense of direction. These policies go unnoticed by voters in the current stormy climate. The challenges at the next election are very different from 1997. The past is a treacherous guide.

In one respect the task is the same at every election. Victorious leaders are like teachers, explaining to voters why they are what they are. The ability to communicate accessibly and constantly is not an extra, but a pre-condition to successful leadership. Labour can win, but it won’t if Miliband and others do not or cannot explain why they should win.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks