Lou Reed: pioneer yes, genius no. That label is reserved for Albert Einstein and Will Shakespeare

Where are all the genius geographers, genius astronomers and genius politicians?

The passing of Lou Reed was a sad moment for rock music. He was a unique talent and a pioneer in the fusion of rock (or pop as it then was) and art. But when I heard that he had died, I knew, just knew, that the g-word would inevitably be appearing.

Sure enough, the next morning in publications as geographically diverse as USA Today, the South China Morning Post and the Times of India, headlines about Lou Reed did not stint from using the g-word. Over here, the Daily Telegraph’s esteemed rock critic didn’t beat about the bush. No waiting until the 10th or 11th paragraph to draw his conclusion. In his opening words he proclaimed: “Lou Reed was a rock and roll genius.”

It is a curious fact that cultural figures in death are rarely just unique talents, never just talents, they are invariably geniuses. And if it’s true of musicians, it is, for some reason, even truer of comedians. In life they may be comedians, in death they are always “a comic genius”. But if comedy has the first claim on the state of genius, music does not lag far behind. Admittedly, acting geniuses are considerably rarer. Dance geniuses are almost unheard of. But tell some good jokes or write some terrific songs and one noun is assured in the coverage of your death.

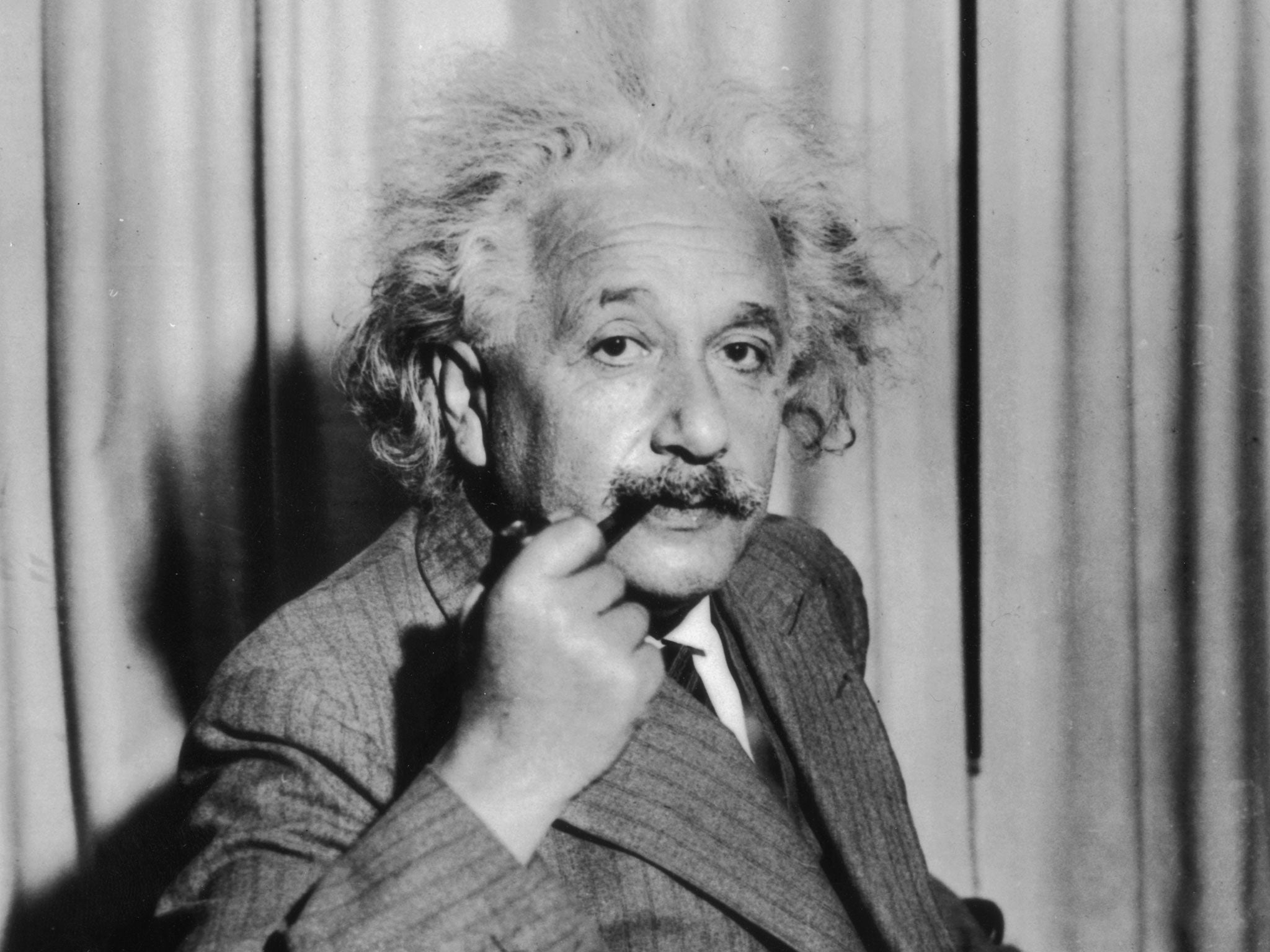

I’ve never quite worked out why the arts claim a monopoly on the word. There don’t seem to be any genius geographers, genius astronomers or, come to that, genius politicians. Even dead scientists seldom seem to merit the g-word, however high the praise of their achievements. But the g-word is a dangerous word. It dulls any true appreciatin of a particular talent, and ignores the various gradations in talent. Not everyone is a genius. In my view, you have to have a mighty strong case to extend the club beyond Shakespeare and Einstein.

It is also a little smug on the part of the arts and on the part of fans and critics to make the assumption that a high achiever in a field about which we are passionate is by definition a genius. One does a disservice to Lou Reed, all those other great dead musicians, all those late comics, a disservice not to try to understand and appreciate their achievements and unique contribution, but instead to use a catch all label that in fact throws little light on greatness and the process by which an artist achieves greatness.

The g-word should be banned. Paradoxically, in being a substitute for genuine analysis and measured appreciation, it can belittle as much as praise.

Film and TV actors and actresses are easily remembered. The record of their work is there on the screen. But stage performers, especially those who do little screen work, tend to be forgotten. This is certainly true in the case of one of the National Theatre’s early stars. Louise Purnell was a leading light in Olivier’s sixties company, transfixing audiences in a number of roles, not least as Abigail in The Crucible. But in all the words that I have read about the National’s 50th birthday, I have not seen one single mention of her, and few now know who she is. However talented you are, whatever impact you make on stage, if you leave the profession early and haven’t diversified into film you are likely to be forgotten 50 years hence. It’s a slightly depressing but salutary lesson.

The art of classical coughing

Delivering the Royal Philharmonic Society annual lecture on the future of classical music, Roger Wright, controller of Radio 3 and director of the Proms digressed to address the matter of coughing at concerts. He concluded: “Audiences only cough when they are uncomfortable or bored.” Wrong, Roger. The cough at a classical music concert is a status symbol, an art form in itself. It is almost a mating ritual, a sign from one classical music regular to another that he or she knows exactly when to cough. He or she will, of course, only cough between movements when there is a symphony being performed. The cough proclaims that the cougher knows his music. Indeed, it is an expression of disdain for those who resist throat clearing between movements, for those non-coughers clearly do not know their music. Far from showing that an audience member is uncomfortable or bored, the cough, expertly delivered and judiciously timed, portrays an audience happy in its comfort zone, and showing its appreciation in the manner to which it has long been accustomed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks