Osborne should choose his guides more carefully

“He told us bad stuff would happen once debt reached 90 per cent of GDP”

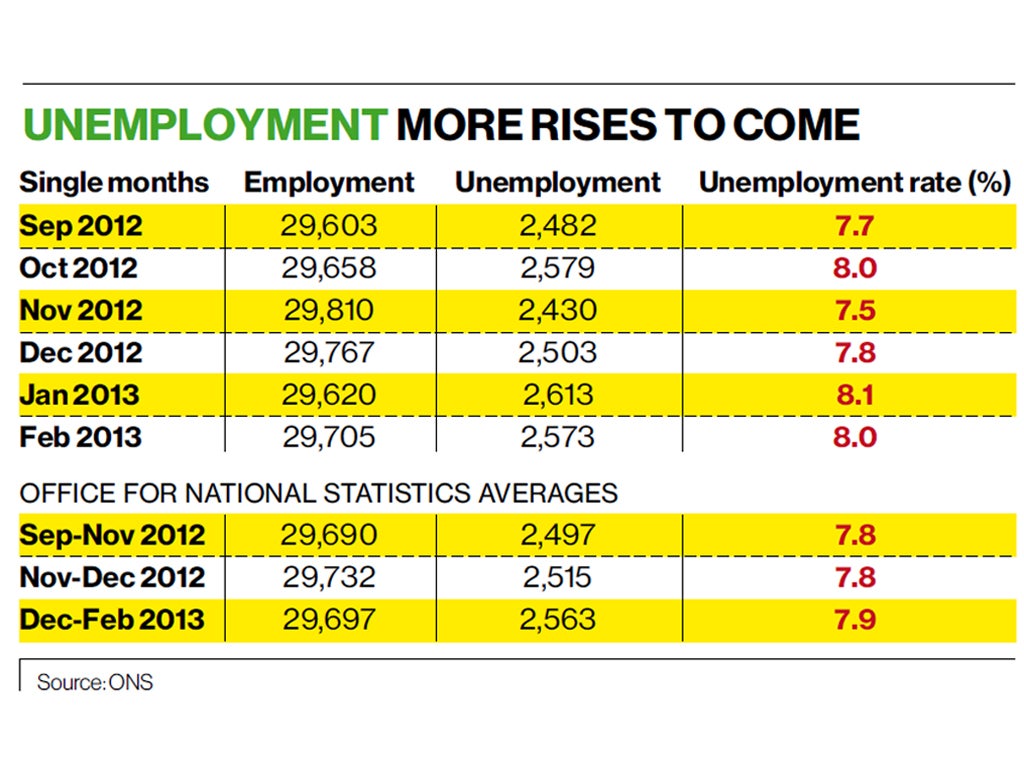

In last week’s column I argued that the unemployment rate was likely to rise this month given that the November 2012 number was an obvious low outlier that was going to be dropped – and so it turned out.

The Office for National Statistics publishes data on the labour market as a three-month average, along with the average for the previous three months. The latest data reported in the final row of the table (right) show that unemployment was 2,563,000 making a rate of 7.9 per cent, up from 7.8 per cent in the previous quarter. These numbers are three-month averages of the single-month data, which the ONS also publishes but does not designate as official national statistics. The point is that each month we know two of the three numbers, and it was clear that dropping November 2012 which had high employment and low unemployment was likely to result in a rise in unemployment and a fall in employment, which it did.

Indeed, it looks like we may well see another rise next month as the low December 2012 unemployment rate will be dropped. For the unemployment rate to fall next month will require the March rate to be 7.4 per cent or lower, which seems unlikely. The best bet is the rate will rise to 8.0 per cent and perhaps even higher. It is also apparent that employment is likely to fall again next month as the 29,767,000 is dropped. It is clear that employment is not at an historic high, as the Coalition has been claiming recently. The Government boasts about the labour market are already starting to look misplaced.

The coldest March since 1892 meant that retail sales for the month were hit with sales volumes off 0.7 per cent on a month-on-month basis, and the annual growth rate negative at -0.5 per cent. The Bank of England’s Agents report was downbeat, with no evidence of any uptick in investment or employment intentions. Based on these weak data, it is a pretty close call whether the ONS will announce that the economy is once again back in recession when GDP data for Q1 is released this week.

Then the International Monetary Fund, who George Osborne used to claim supported his every move, lowered its growth forecast for the UK for 2013 and 2014 by more than for any other advanced country. The IMF now forecasts growth of 0.7 per cent in 2013 and 1.5 per cent in 2014 – down by 0.3 per cent each year. In a major blow to our part-time, downgraded Chancellor it argued that “in the United Kingdom, where recovery is weak owing to lacklustre demand, consideration should be given to greater near-term flexibility in the fiscal adjustment path”.

Indeed the IMF’s chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, suggested that Osborne should rethink his economic plans in light of the continuing weakness of the UK economy. “There is a point at which you actually have to sit down and say maybe our assumptions were not right and maybe we have to slow down,” the economist said. It seems to me that point was reached ages ago.

Most significantly, a paper by three professors from the University of Massachusetts put the tin hat on Slasher’s week by showing that the work of Reinhart and Rogoff (RR) on the negative effects of debt on growth was riddled with holes. In his Mais lecture of February 2010, Osborne said really bad stuff would happen when debt passed 90 per cent of GDP because RR told us so.

He said: “Perhaps the most significant contribution to our understanding of the origins of the crisis has been made by Professor Ken Rogoff, former chief economist at the IMF, and his co-author Carmen Reinhart… [who] demonstrate convincingly, all financial crises ultimately have their origins in one thing — rapid and unsustainable increases in debt. The latest research suggests that once debt reaches more than about 90 per cent of GDP the risks of a large negative impact on long-term growth become highly significant.” So the way to get growth according to Osborne was through a new economic model of tight fiscal policy and supportive monetary policy. That was never going to work and hasn’t.

Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin (HAP), in a devastating critique* of RR’s anti-debt work, find that coding errors, errors of basic arithmetic, selective exclusion of data on high-debt countries with decent growth immediately after the Second World War, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics lead to serious errors that “inaccurately represent the relationship between public debt and GDP growth among 20 advanced economies in the post-war period”.

HAP’s finding is that when properly calculated, the average real GDP growth rate for countries carrying a public debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 90 per cent is actually 2.2 per cent, not minus 0.1 per cent as published in RR. That is, contrary to RR, average GDP growth at public debt/GDP ratios over 90 per cent is not dramatically different than when debt/GDP ratios are lower. HAP conclude that, “the evidence they review contradicts RR’s claim to have identified an important stylised fact, that public debt loads greater than 90 per cent of GDP consistently reduce GDP growth”.

RR admit to arithmetic mistakes but argue “we do not believe this regrettable slip affects in any significant way the central message of the paper or that in our subsequent work”. But few are convinced because the results, at the very least, look highly fragile. Lots of economists, especially Paul Krugman, doubted the results in the first place because the observed correlation between debt and growth probably reflected reverse causation. Lack of growth, as in the UK, raises debt. As Krugman has noted in a recent blog “the really guilty parties here are all the people who seized on a disputed research result, knowing nothing about the research, because it said what they wanted to hear.”

It is not surprising George Osborne had a tear in his eye this week as the economic walls of his misguided and failed economic strategy have crumbled around him. The world was watching Osborne’s austerity experiment to see what happened. They now know. It failed.

* Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin ,“Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks