The Swedish shock wave is a lesson. We could have unrest here without action on jobs

The evidence from behavioural economics is that people compare themselves to others

A shock wave was sent around Europe by the riots that occurred over several nights in Sweden.

It started in Stockholm and spread fast. Several suburbs of the city witnessed arson attacks and violence against police who had been called in to limit the damage. Dozens of people, primarily youngsters, were arrested and more than 100 cars set on fire.

The rioting occurred principally in poor and immigrant neighborhoods like Husby. Rioting spread to a dozen other cities including Orebro in central Sweden.

This seemed like the last place where there would be unrest as Sweden is the poster child of the nanny state. Sweden has not suffered as severe an economic slump as some other countries in the European Union (EU); it grew by 0.8 per cent in 2012, compared to the 0.6 per cent decline in the eurozone.

It was surely not a coincidence that European leaders warned this week that youth unemployment could lead to widespread social unrest. Amazing they hadn’t worked that out before. Talk about too little too bloody late, not to mention stables and horses heading into the sunset without closing the doors behind them.

Youth unemployment rates in the eurozone and the EU are now 24 per cent. Young people have a higher propensity for civil unrest than older people. The big surprise actually is that the young have been so compliant. It is surprising that social disorder has not occurred on a much greater scale than it has to this point given the harshness of austerity in so many countries.

The fear is that the riots in Sweden could pop up in other parts of Europe. Everyone remembers how the riots spread like wildfire across the UK in 2011. The French, German and Italian governments have launched initiatives to help the young but they will take some time to have an effect.

Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, warned that unless Europe tackled youth employment, it “will lose the battle for Europe’s unity”. Panic has set in. After all , riots do tend to grab politicians’ attention.

But things have been changing. Inequality is on the rise. Indeed, between 1985 and 2010, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Sweden saw the biggest growth in inequality of all the 31 most-industrialised countries.

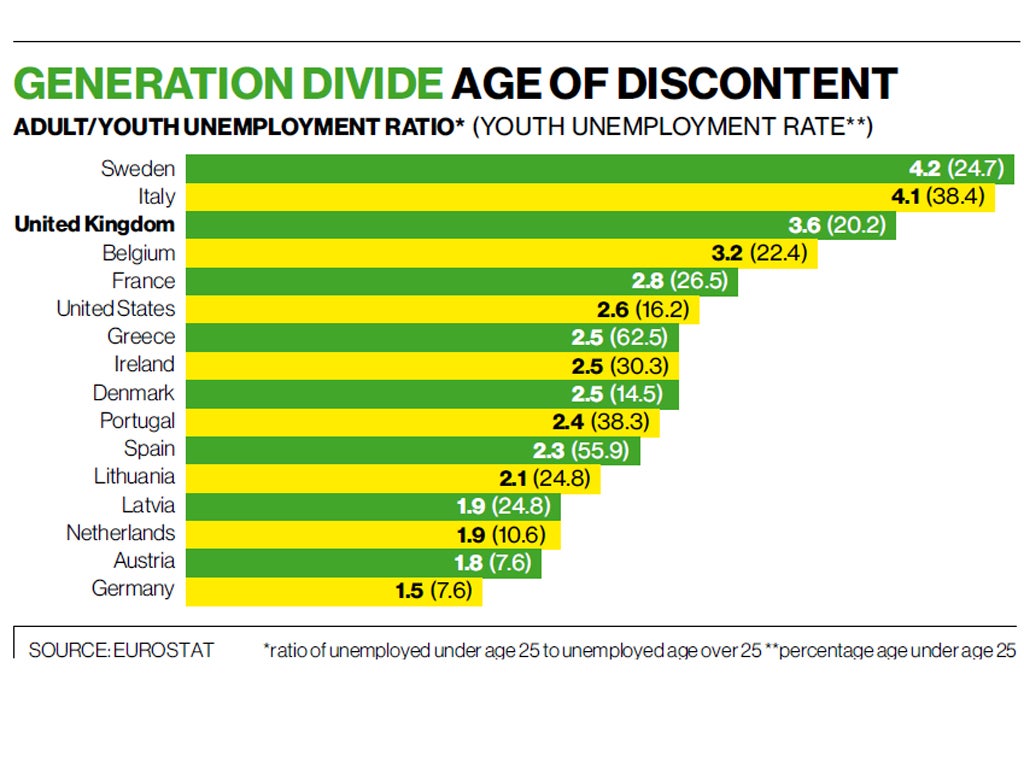

The chart above presents for 16 advanced countries the ratio of unemployment rates of those aged 25 and under to those aged over 25. It also shows the youth-unemployment rate. The chart is ordered according to the youth-to-adult unemployment ratio with the youth unemployment rate in parentheses.

As can be seen from the chart, youth unemployment in Sweden is pretty high, approaching 25 per cent, although well below the levels seen in Greece (63 per cent), Spain (56 per cent) Portugal and Italy (38 per cent). It is also higher than the rate in the UK (20 per cent). Sweden has also seen a significant rise in long-term youth joblessness. Rates tend to be even higher than this in most countries for the least-educated, minorities and immigrants. According to the Office for National Statistics Annual Population Survey, age 16-24 unemployment rates in London in 2012 were 19 per cent for whites, 24 per cent for Indians, 44 per cent for Pakistanis, 38 per cent for Bangladeshis and 44 per cent for Black/African/Caribbeans. In the light of recent events in the capital these numbers are troubling.

But what stands out from the chart is the ratio of youth rates to adult rates, which at 4.2 in Sweden is the highest among this group of 16 countries. The evidence from behavioural economics is that relative things matter – people compare themselves to others. So a big gap between young and old unemployment rates may well become a big problem when youngsters are hurting more than their older peers. That may well generate conflict. At a ratio of 3.6 the UK ranks a worrying third in this list. Germany has the lowest ratio and the US is in the middle of the pack with a relatively low youth unemployment rate of 16 per cent.

It isn’t as if the Swedes weren’t warned. In 2012 the OECD in its country report for Sweden cautioned presciently that “some groups such as youth with limited education, some immigrants, and those on sickness and disability benefits are not well integrated”. In Stockholm in November 2010 I presented a paper with David Bell which examined youth unemployment as well as its potential consequences.*

The discussant for the paper was the Swedish finance minister, Anders Borg. In that paper we showed that early adulthood unemployment creates long-lasting scars, which affect labour market outcomes much later in life. Given these negative effects of early unemployment experience, we suggested that an appropriate policy response would be to change the balance of demand in favour of younger workers.

We suggested that “this age group was not responsible for the recession. It should not be expected to pay for it through potentially long-run, adverse labour market outcomes”. Little was done and the young are being hit hardest almost everywhere.

If it happened there it could easily happen here once more. The most recent data shows 1.09 million aged 16 to 24 in the UK were not in education, employment or training, up 21,000 from the previous quarter. Appallingly, approximately 275,000 youngsters have been unemployed for at least a year and 100,000 for more than two years. These are the kids who stand to be damaged.

The Government scrapped the Future Jobs Fund and the Educational Maintenance Allowance that worked and replaced them with the useless Work Programme that doesn’t.

The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Iain Duncan Smith, who was criticised by the head of the UK statistics authority earlier this month for making unsupported claims, had better put his mind to how he is going to solve our youth unemployment problem and quickly, before he has a disaster on his hands. Do something.

*David Bell and David Blanchflower, “Youth unemployment in Europe and the United States”, Nordic Economic Policy Review, number 1, 2011, pp. 11-38

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks