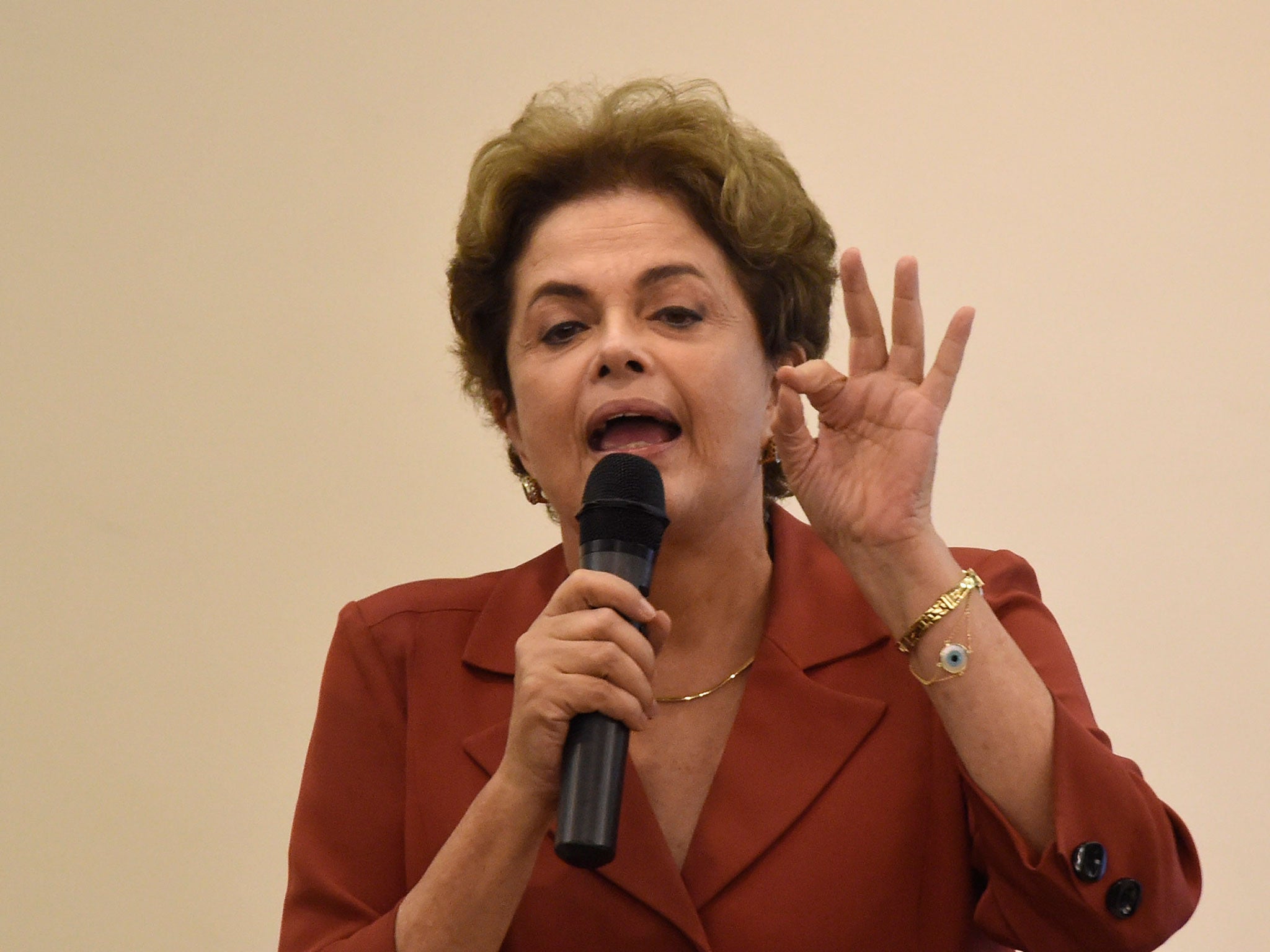

Dilma Rousseff will be remembered in Brazil's history books for more than recession and corruption

The deposed Brazilian president was overwhelmed by a position she was never qualified to hold

Back in March 2014, when the scandal over Brazil’s state-run oil company Petrobras that would eventually topple the government was just getting started, some of President Dilma Rousseff’s top aides saw a golden opportunity to kill the investigation – or at least badly wound it.

Márcio Anselmo, the Federal Police deputy in charge of the probe, had given an interview to Jornal Nacional, Brazil’s most-watched news programme. On-camera, Anselmo and others laid out the main points of the case, which would soon become notorious: a former Petrobras board member who had accepted a Land Rover as a bribe, the money launderer whose plea-bargain testimony would prove key, and the bribes paid by some of the country’s biggest construction companies for lucrative Petrobras contracts.

For President Rousseff, the stakes were huge: The presidential election was just six months away, and she was facing a tight race. But some ministers were convinced the TV interview was a blessing in disguise. They believed Anselmo had broken a dictatorship-era statute that, they argued, prohibited Federal Police officials from discussing cases in progress with the media. Fire him, they urged. Fire him now and attack the investigators for using the media to selectively leak information damaging to the government.

To their astonishment, President Rousseff refused. “I’ll never do that,” she replied dismissively, according to someone who was in the room. “I’m not afraid of this investigation. It has nothing to do with me.”

I covered President Rousseff – known as Dilma – closely for five years as a reporter and there are not too many anecdotes about her I do not know. This one has it all: her blustery arrogance, her refusal to listen to even her closest aides and her apparent inability to understand just how much trouble she was in, right to the very end. But it also reveals a side to her that should improve her standing in the annals of Brazilian history: her refusal, for the most part, to stand in the way of corruption investigations at Petrobras and elsewhere, even when it became clear they would contribute to her demise.

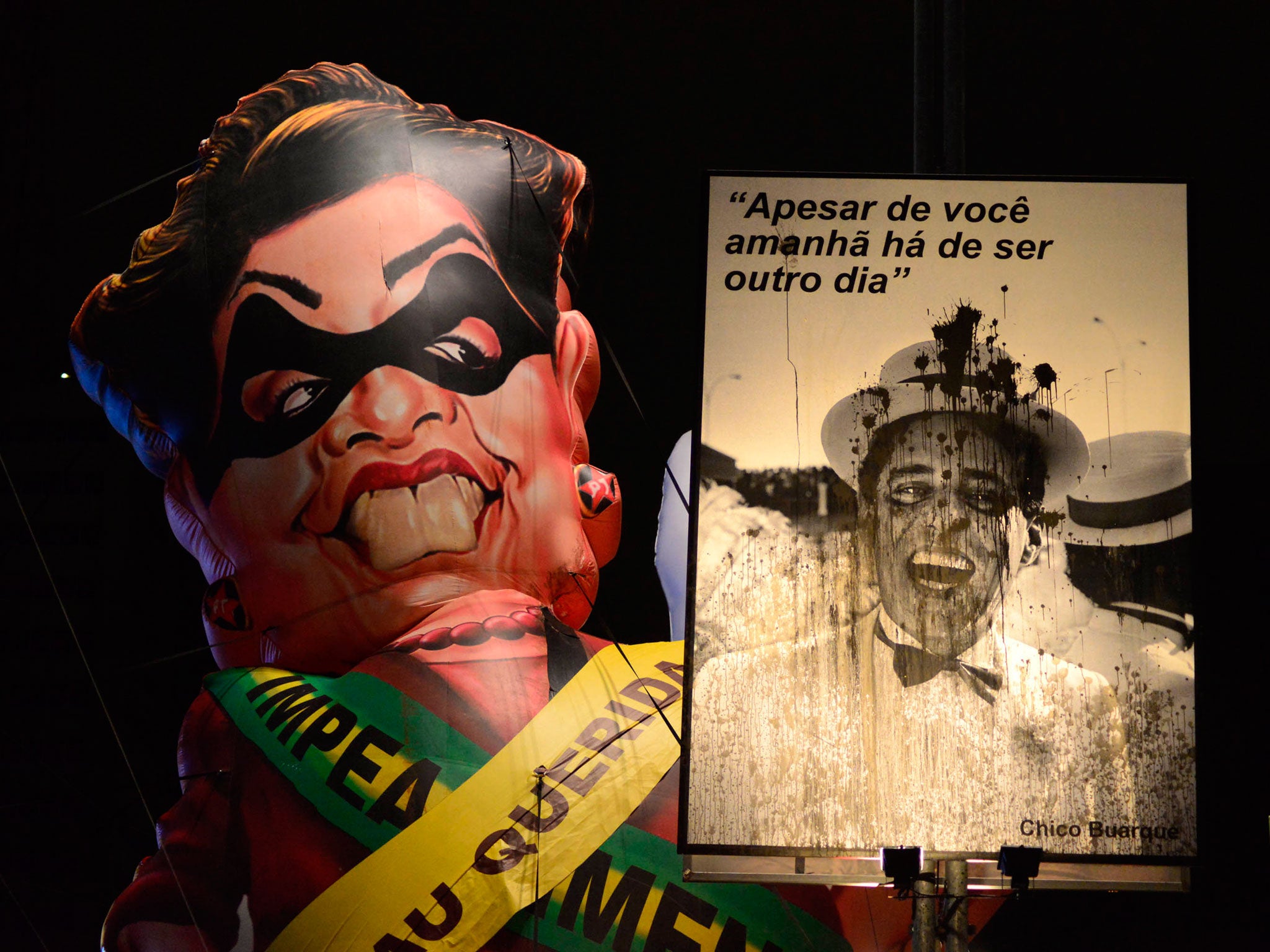

Brazil’s Congress has now voted to remove President Rousseff from office, almost certainly for good, so she can stand trial for breaking budget laws in a way that masked Brazil’s economic woes. She departs with a near-single-digit approval rating, primary responsibility for Brazil’s worst recession in at least 80 years, and very few friends at home or abroad. And yet, she also deserves some credit for the main achievement of this otherwise horrid decade in Brazil: the consolidation of the rule of law under its young democracy, as well as the notion that the corrupt will be investigated, convicted and jailed, no matter how powerful they may be.

Acknowledging Rousseff’s role in this achievement is controversial, in part because her behaviour also was not impeccable here. Indeed, she may soon face charges for obstruction of justice for appointing her mentor and predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as Lula, as a minister in her final days in government at a time when prosecutors were seeking his arrest on corruption charges. The move was widely seen as designed to make Lula less susceptible to imprisonment, since ministers enjoy special legal protections. But it may have been less an attempt to hinder the investigation itself and more an act of personal loyalty and realpolitik, based on the belief that only Lula had the negotiating prowess to save her government.

Starting in early 2014, Rousseff had numerous opportunities to hinder, or at least delay, the investigation of Petrobras and other high-profile corruption cases targeting powerful people. The argument against Anselmo, the Federal Police deputy, seems in retrospect to be flimsy – but in any case she let the opportunity pass. She could have declined in 2015 to reappoint the attorney general, Rodrigo Janot, who had already shown he would go along with the so-called Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) probe. She not only retained Janot but also publicly reaffirmed his autonomy – a mandate he would soon seize upon by requesting charges against Lula and an investigation of Rousseff.

Rousseff also could have put someone less apt to cooperate with prosecutors in charge of the Federal Police or actively pressed her allies on the Supreme Court to remove the Petrobras case from Judge Sérgio Moro, who is based in the city of Curitiba, on the argument that judges in Rio de Janeiro, where the company is based, were better-suited to handle it. Finally, she could have started attacking Moro as biased much earlier and more aggressively than she ultimately did.

All along, Rousseff had senior figures within the Workers’ Party urging her to do all of these things. But instead, as recently as January of this year, she was publicly celebrating Lava Jato as a necessary purge of practices that had existed in Brazil for decades. “I have to emphasise the fact that Brazil needs this investigation,” she told the newspaper Folha de S.Paulo, limiting her criticism to procedural issues. Rousseff didn’t begin to vilify the investigation in earnest until a few weeks ago, when Moro released wiretapped conversations between her and Lula. And there… well, let’s say she may have had a point.

There are those who will never give Rousseff any credit for letting Brazil’s judiciary do its job. What choice did she have, they ask. OK. But ask yourself the following: would leaders elsewhere in Latin America have done the same? What about recent governments in Argentina? Or Mexico? Not to mention China or Russia. For that matter, what can we expect from the incoming Michel Temer government in Brazil?

Temer, who was Rousseff’s vice-president, is a 75-year-old constitutional lawyer who will try to lead Brazil in a more business-friendly direction. But he comes from a different political party, several of whose leaders are also implicated in the Lava Jato probe. One irony of Rousseff’s impeachment is that it may lead to more political interference in the Petrobras investigation. Temer has said there’s nothing to fear, but prosecutors in Curitiba and Brasília privately say they are preparing for setbacks. They may end up missing Rousseff most of all.

So the final question: why did she do it? Why did Rousseff stand by as her government fell apart? Some of the explanation probably lies in her origin story. Not the one we’ve all heard about – the Dilma Rousseff of her early twenties, the guerrilla who endured jail and torture. No, I’m talking about Dilma Rousseff the adult, after her release from prison in 1973, the one who undertook a much less glamorous life as an economist and public servant. This is the bespectacled energy policy wonk who just 20 years ago was editing an obscure magazine called Economic Indicators and never showed any interest in politics or higher office. This Rousseff’s only passion was for numbers – performance targets, spreadsheets, the arcane day-to-day business of government.

Even after Lula plucked her from nowhere to be his chief of staff and ultimately his successor, even after the plastic surgery and makeover that preceded Rousseff’s run for president, she still had no time for anything but numbers. Unfortunately for Rousseff, this prevented her from making any friends, in Congress or elsewhere, who might have protected her toward the end. But it also made her intolerant of corruption – not for moral reasons, perhaps, but because it might keep the numbers in the G column on Excel from lining up correctly.

From the very beginning of Rousseff’s government, when a minister or other aide was accused of fraud, she made it clear that person was expected to resign. Six ministers left under such circumstances during her first year in office. This was a radical departure from the Lula years, and it contributed to a new culture that ultimately resulted in Lava Jato.

Of course, there are other, much less flattering explanations. It’s clear that Rousseff, isolated and politically tone-deaf, failed until it was too late to fully grasp the threat to her survival. The Rousseff-as-earnest-technocrat theory also has a major hole in it: if she was so focused on numbers, how did she miss the sheer scale of the robbery at Petrobras, especially during the years she was energy minister and the chair of the company’s board?

The answer probably lies in the simplest, most damning criticism of Rousseff: she just wasn’t that good. Mediocre to the end and overwhelmed by a position she was never qualified to hold, she consistently failed to ask the right questions of her aides or her party. She also harboured antiquated economic philosophies, believed she could dictate the day-to-day business of the country (including parts of the private sector ) by personal fiat and alienated most people she worked with. Her presidency will go down as a case study in why leadership matters –why a democracy as big and complex as Brazil’s cannot simply be handed over to anyone and put on “automatic pilot”.

But Rousseff had virtues too. Even her enemies concede she was honest and stole nothing for herself. In a region where many leaders spend their waking hours scheming about how to make themselves or their friends richer or exact revenge on their enemies, Rousseff seemed genuinely focused on tackling Brazil’s still-legendary poverty and inequality. And in the end, any desire she had to stay in office or protect her party seems to have been outweighed by a long-term concern for Brazil and the need to build functioning institutions. That should count for something.

This article was first published by ‘Americas Quarterly’, where Brian Winter is the editor-in-chief

© IBT Media

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks