Immigration is good for growth, so why is the public so hostile to it?

If people think high migration and a rising population are a problem, they should consider the alternative

Few subjects expose the gulf between economists and many ordinary people better than immigration. Writing in 1979, JK Galbraith summed up the view of many economists on the subject of the movement of peoples across national borders: “Migration is the oldest action against poverty. It selects those who most want help. It is good for the country to which they go. It helps break the equilibrium of poverty in the country from which they come.”

Net migration (immigration minus emigration) to the UK hit a record high of 336,000 in the year to June, according to the Office for National Statistics. This has prompted not Galbraithian celebration, but a dismal round of lamentation and recrimination. Yet the economic case for immigration is as robust as it was 36 years ago when Galbraith laid it out.

Empirical evidence shows that money sent home to migrants’ families in poor countries is well spent. These funds enable households to spend more on health and education for their children, driving domestic development and curbing poverty. And for rich countries there is decent evidence that immigration boosts productivity, the magic ingredient that drives overall economic growth.

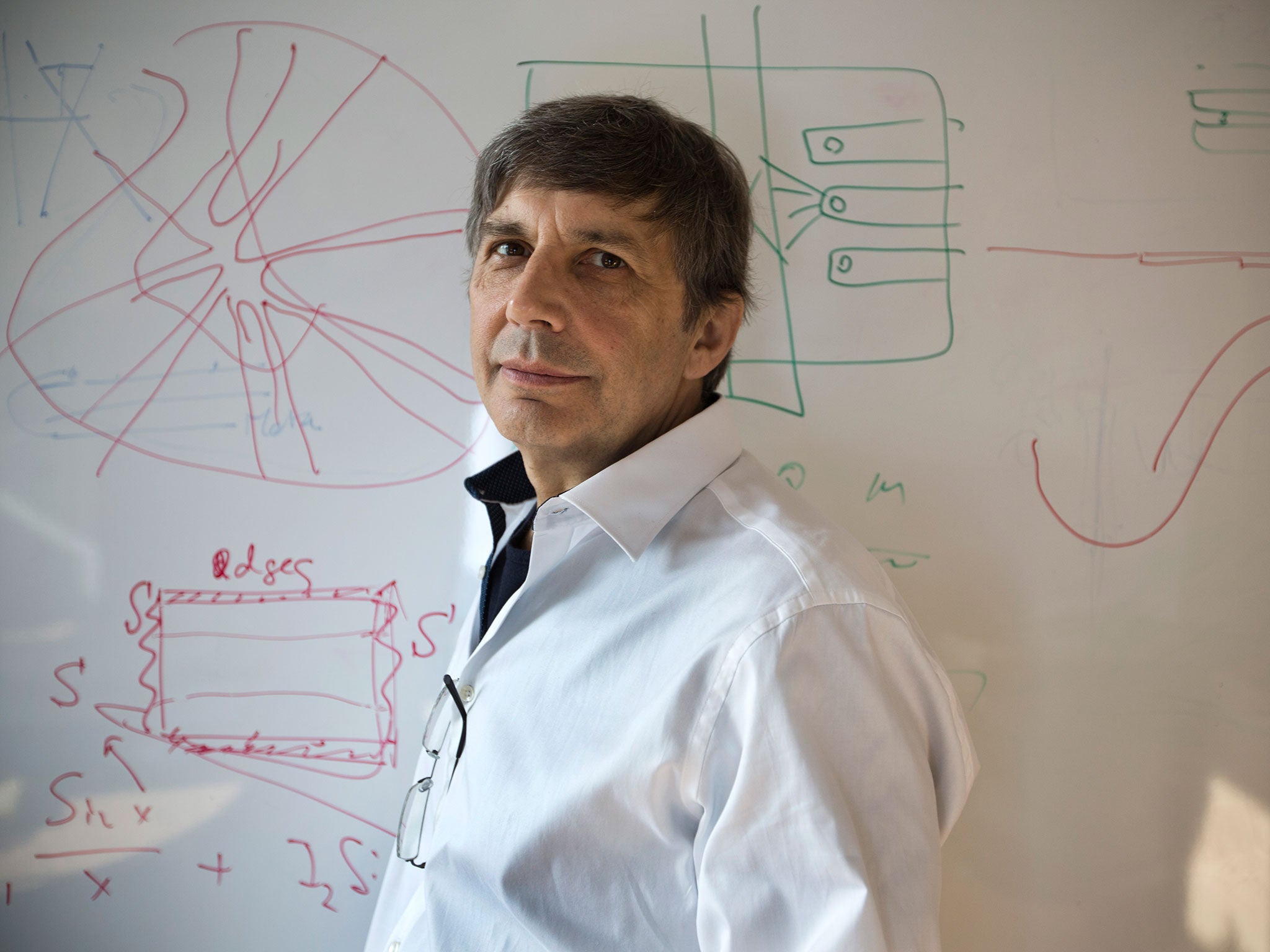

Some high-profile examples demonstrate how that process works. Graphene was isolated at Manchester University by Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov, two immigrants from Russia. There are high hopes that this special industrial material will create a host of entirely new markets, boosting our national income in the process. The history of California’s Silicon Valley is testament to the powerful role of the entrepreneurial immigrant. Sergey Brin, one of the founders of Google, was Russian-born. Steve Jobs, the irascible but brilliant founder of Apple, was the son of Syrian migrant.

Not all contributions need be so stunning for immigration to drive growth. By filling skills gaps in the workforce and starting businesses, immigrants tend to improve national economic efficiency. The history of ethnic Chinese migrants to neighbouring South-east Asian countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines vividly shows this beneficial effect. Many of these expat Chinese communities run thriving import-export businesses.

There is a short-term economic boost for the host country, too. Immigrants tend to be of working age. They are also very keen to work, which shouldn’t be surprising given that it takes a certain level of self-belief and drive to leave your native country in search of new economic opportunities elsewhere. That is why the Office for Budget Responsibility revised upwards its potential growth forecasts for the UK on the back of some higher net immigration assumptions at the Autumn Statement. There is no conspiracy here: this economic fillip is what the historic data suggest is the impact of higher migration, and forecasters duly write it in.

You can hear the economic benefit spelt out by businesses themselves. Carolyn Fairbairn, the new head of the Confederation of British Industry, called this week for the Government’s cap on non-EU immigration to be relaxed to enable firms “to bring in the best talent from around the world”. She cited serious skills shortages in computer science, engineering, design and advanced manufacturing.

But while Chancellor George Osborne may be minded to listen, other ministers are not. When the latest migration figures were published, the Immigration minister, James Brokenshire, blamed British employers for being “overly reliant” on foreign workers. Similarly, the Home Secretary, Theresa May, gave a speech at the Conservative Party conference earlier this year in which she claimed that immigration had “forced” some native Britons out of work – a bizarre assertion given that her government is trumpeting the fact that the overall UK employment rate is at a record high.

Economic growth isn’t everything, but it is terribly important for meeting expectations of higher living standards. The Japanese birth rate is so low that the overall population is declining. Without a baby boom or a burst of immigration, its population is set to contract by a quarter by the middle of the century, creating an array of economic nightmares such as the hollowing out of entire communities and a lack of workers to care for the extremely old. Germany is facing a similar challenge.

If people think that high migration and a rising population are an economic problem, they should consider the alternative.

Economic growth isn't everything but it is notable also that popular anxiety about immigration usually takes expression as a complaint about its impact on native jobs and wages. It is often said that while immigration might be good for rich people (who, for example, can employ cheaper cleaners), it hurts the living standards of everyone else. Yet there is no evidence of immigration holding down wages, beyond those at the very bottom – and even there the effect is negligible. Despite May’s assertions about displacement, there is no evidence of people being pushed out of the workforce either. Immigrants seem to fill gaps that would not otherwise be filled. So why the public hostility?

Another common complaint is that a flow of new residents places stress on transport, health and housing. This is, in fact, a complaint about the lack of infrastructure and public services investment, as much as a complaint about the presence of migrants. It is true that average wages seem to have decoupled from national productivity growth – even more so in the US, where Donald Trump has been riding a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment. Blaming immigrants for wage stagnation may be as much about the skewed distribution of the benefits of growth as anything else.

“What is the perversity in the human soul that causes people to resist so obvious a good?” wondered Galbraith about immigration. Perhaps the answer is that people are not resisting immigration so much as the failure of governments to ensure that its short-term pressures are managed and that the economic rewards that flow from the international movement of people are broadly shared.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks