Shameful case of Lord Bramall is only the latest in a catalogue of police failures and cover-ups

Given the long history of such failures, the prospects for a final resolution are poor

The job of any police officer – dealing with drunken youths on a Saturday night, comforting victims of sexual abuse, or trying to track the movements of suspected terrorists intent on killing and maiming British citizens – is often thankless and wilfully misunderstood. The views of armchair chief constables are often as misguided as they are ill-informed. Most police officers most of the time fulfil their sworn duty with bravery and dedication.

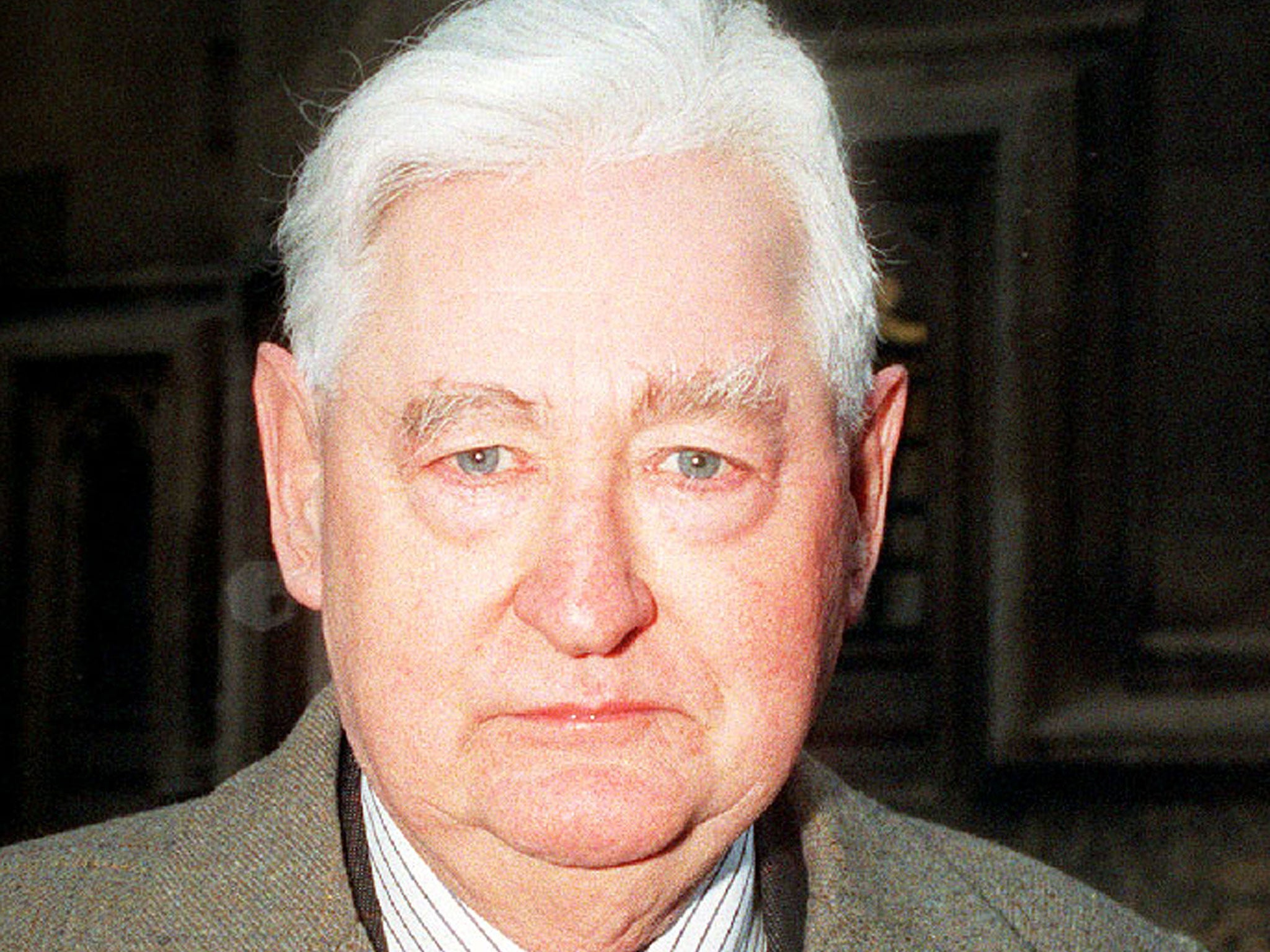

Yet even the most understanding observer of the performance of the Metropolitan Police is left troubled by a substantial, and dispiriting, list of bungles and failings. These can be doing morale in the service no good, and are damaging its reputation. The latest is the collapse of the case against Lord Bramall. Much is made of his age, his distinguished war service and his achievement in rising to the highest rank in the Army. He is also 92. But the Met’s behaviour would have been wrong no matter whom it were pursuing, because it took too long and was too secretive during the course of its investigations.

Lord Bramall and his family should have had matters resolved far sooner than they were. Of course, historical allegations are difficult to deal with by their nature, but the extreme lengths of time involved in this case – given the age of the people involved – do raise some difficult questions. Nor has the Met been gracious at the conclusion of its inquiries. No apology, or anything like it, appears to have been offered by the Met or its Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe. The least it could do is offer an explanation, given the public profile of the man involved and the reputational damage suffered. To the best of our knowledge, the Met has ruined the life of an innocent man, and that cannot be right.

It adds to a litany of failings that have become wearily familiar. Whatever else we know about phone hacking and the transgressions of the British press highlighted by the Leveson inquiry, we do know that the Met and journalists at leading newspapers had an unhealthy, unethical relationship, the truth of which may never be fully known. The Met was plainly too close to a newspaper executive it lent a horse to, much as Rebekah Brooks appreciated it. The shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes might have been justified had some of the claims made by the Met been correct; but too much doubt had been cast on the detail for anyone to believe that the Met had acted defensibly. Much the same could be said about the death of bystander Ian Tomlinson during a demo in the City.

More trivially, we can also recall the morass of Andrew Mitchell and Plebgate, a waste of vast amounts of political and police time. Farther back, we have the ringing echoes of the Macpherson report into the death of Stephen Lawrence and its conclusions about “institutional racism”. Indeed, and more broadly than the Met, the more we learn about police behaviour during events such as the Hillsborough disaster, the miners’ strike and the infiltration of green and other protest groups in the 1980s, the less faith we can have in them.

All these abuses happened decades ago; but if we did not know the truth then, how can we be confident that equivalent abuses are not happening now? When the police have the opportunity and the means, for example, to snoop on emails and web histories, how can we be sure that they are targeting only would-be jihadists? We should also be wary of arming yet more officers.

Given the long history of such failures – with the Met probably reaching its financially corrupt nadir in about 1972 – the prospects for a final resolution are poor. What seems to have worked in the past is review by other forces and independent bodies, fresh leadership, greater scrutiny by democratically elected representatives, and more intense independent scrutiny by the media. None of these seems to be much in evidence. It may take a few more scandals.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments