Erdogan’s new powers will spark fears of creeping authoritarianism

It was never going to be simple

It was never going to be simple.

Turkey faces a complicated web of problems – a rekindled war between the state and Kurdish militants, repeated attacks claimed by Isis stemming from the country’s role in the Syria conflict, and the state of emergency that is still in place following the failed coup against the government last year.

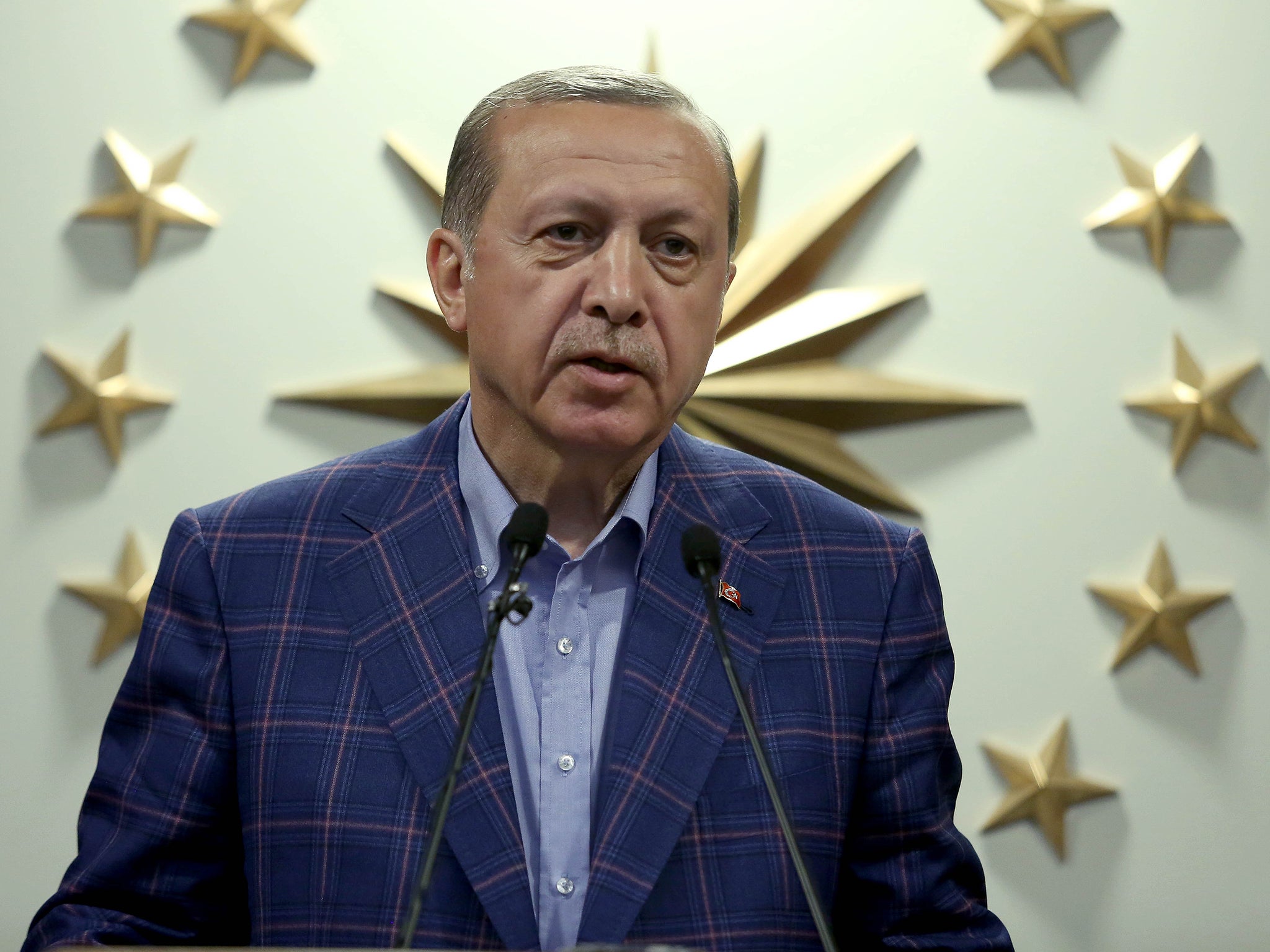

However, for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the unstable nature of his country has enabled him to project the strongman image that may just allow him to extend his powers.

Those sweeping new powers will turn the largely ceremonial presidential role he now holds into a nearly all-powerful position as head of government, head of state and head of the ruling party.

The presidential position was created to be neutral, with the holder of the post expected to cut all ties with their party. In appearance at least, Mr Erdogan did that in 2014, when he became the first person directly elected into the position instead of being chosen by parliament. That ended 11 years as Prime Minister and head of the Justice and Development party (AKP) he helped found.

However, the former prime minister said he wanted to be an “active” president, something that has been on his mind for a while, and as for giving up on the leadership of the AKP, he pulls too many strings for that to be anything more than window dressing.

The constitutional change for an executive presidency had been mooted by his ruling AKP back in 2011, with Prime Minister Erdogan being unable to run for a fourth term – and its adoption now would open the door for Mr Erdogan to rule possibly until 2029.

To his supporters Mr Erdogan is a man who has given a voice to the working and middle-class religious Turks who had felt marginalised by the country's Western-leaning elite. He was seen to have ushered in a period of stability and economic prosperity, building roads, schools, hospitals and airports in previously neglected areas.

Others see him as pushing too much of a religious line in a nation that was built on the secular aspirations of Turkey’s modern founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

The constitutional amendments would give the president the power to appoint ministers and government officials, to name half the members of the country's highest judicial body, to issue decrees and to declare states of emergency.

That raises the alarm for many. Mr Erdogan has long-faced accusations by critics of using the judiciary to silence opponents, and journalists groups have often spoken out of the stifling of their freedom to report – with many more civilians worried about the implications of a move to ‘one-man rule’. Hence the close result in the referendum.

Despite what many citizens see as Mr Erdogan’s commitment to the safety of his country’s citizens from the multitude of threats they currently face, as he has become more powerful, his critics say he has become increasingly authoritarian.

His election campaigns have been forceful and bitter, with Mr Erdogan lashing out at his opponents, accusing them of endangering the country and even supporting terrorism – either in Syria or the insurgency of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

After surviving the attempted coup in July he launched a wide-ranging crackdown on followers of his former ally, Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen.

Mr Erdogan and his government blame Mr Gulen, who lives in the United States, and his supporters for plotting the coup, an allegation the cleric has denied.

The crackdown saw roughly 100,000 people lose their jobs, including judges, lawyers, teachers, journalists, military officers and police. More than 40,000 people have been arrested and jailed, including pro-Kurdish MPs.

Hundreds of non-governmental organisations and news outlets have been shut down, as have many businesses, from schools to fertility clinics.

It is fears over Mr Erdogan having free rein to push further with such purges that may be one of the reasons opposition parties are appealing the result – the will of the people is fine, but there must be no hint of any foul play.

Outside of Turkey, the EU will likely be worried, with several nations, including Germany and the Netherlands having clashed with Mr Erdogan over campaigning for Sunday’s referendum. There is also the small case of potential talks over Turkey’s ascension to the EU, stopped over Mr Erdogan’s apparent support for the return of the death penalty in the wake of the attempted coup. A theme that Mr Erdogan has returned to in remarks following the referendum vote results.

The EU also needs Turkey’s help in dealing with the refugee crisis in the bloc, and stemming the flow of new arrivals – a thorny issue that will not disappear. The potential new reality in Turkey will certainly create difficulties, with decisions potentially based on the whim on the President.

But as supporters of Mr Erdogan pour onto the streets of Istanbul and other cities, in a similar way to the night of the attempted coup which helped to stifle the insurrection – it appears Turkey’s President will emerge the victor, not matter how many appeals come in over the result of the referendum vote – just as he has many times before.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks