London's galloping high-rise developments face a backlash from protest movement

The seemingly unstoppable rise of glass-and-steel developments has caused a backlash on a scale not seen since the 1960s. But what kind of cities do protesters want to see? Oliver Bennett reports

London is starting to look like Dubai or Shanghai – even Oz's Emerald City. Shimmering skyscrapers soar from sooty arterial roads. These glass and steel spores are encroaching on other cities, too; meanwhile rural towns are being circled by speculative housing. As the UK emerges from the crash, building is looking healthy. Construction employs 2.5 million people, it's a highly visible totem of economic dynamism, and the Government's stated need to build 290,500 homes each year until 2031 – 49,000 of this rolling total in London alone – finds few critics.

So why is dissatisfaction brewing at a scale unseen since the conservation movement of the 1960s, when the fall of the Euston Arch and the proposed destruction of Covent Garden galvanised a generation? For London's galloping developments are infuriating an ever-widening group of people on all kinds of fronts: architectural, environmental, civic, social. Currently attracting public ire in the capital are a growing glut of contentious sites including Bishopsgate Goods Yard (described by the newly convened East End Preservation Society as "intrusive and alien" – protesters even include Hackney's mayor, Jules Pipe) and developments at Swiss Cottage, Nine Elms, Earls Court, Elephant and Castle, the Shell Centre on the South Bank… The list goes on, including one on my patch, Mount Pleasant in London EC1, owned by the Royal Mail Group (RMG).

I've been involved in a campaign to try to change the nature of this development on my doorstep, and while discontent lies mainly in the plans – an unfriendly fortress-like development of bland but expensive-to-be flats (called "apartments", natch) with negligible amenities – the high-handedness of the process has really delivered the blind-sider to locals. The added kicker was that Boris Johnson insulted objectors as "bourgeois nimbys".

If arguing that the development was too high, lacked amenities, blocked out light, created wind tunnels and, ultimately, was at odds with the neighbourhood is "bourgeois nimbyism", then I'm guilty as charged. But I'm far from the only person concerned about this kind of development, and it's not just in my backyard. While the Mount Pleasant Association, of which I'm a member, was set up to protest against the RMG plans, it has found itself part of a fast-growing protest movement that is now reaching directly into Government, with the constructive aim to change planning policy for the better.

Most notable, if already contentious, is a newly convened government panel aiming to set housing-design standards in the UK, composed of conservative philosopher Roger Scruton, master-planner Sir Terry Farrell, who oversaw 2014's Farrell Review on architecture (a national "whither the nation?" appraisal of architecture and the built environment), and neoclassical architect Quinlan Terry, who was appointed by David Cameron last month. Quinlan Terry, famously Prince Charles's favourite architect, is a traditionalist whose work has been described by his critics as "neoclassical pastiche". Scruton is a fan of his. Sir Terry is less clear: he's a major architect and master-planner, but makes friendly noises about incremental improvements to high streets and neighbourhoods. The Review proposed that planning champions should be appointed across the country to oppose unpopular developments.

With the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Royal Town Planning Institute and the Design Council also in attendance, the panel's first meeting took place last month, following an agenda set by the lobby group Create Streets, led by the ex-financier Nicholas Boys Smith, which promotes streets, squares, houses and mid-rise flats rather than the current trend for glass-and-steel towers of the type seen on Islington's City Road.

Indeed, Create Streets has helped to organise alternative plans for Mount Pleasant by Francis Terry (Quinlan Terry's equally neoclassical son) of Quinlan & Francis Terry Architects, consisting of mid-rise classical terraces around a central "circus", as opposed to the more or less hi-tech RMG plans by Wilkinson Eyre, AHMM, Feilden Clegg Bradley, and Allies & Morrison.

Create Streets' big idea is that the housing crisis, as well as the experience of living in London, would be better served by building streets, not multi-storey blocks.

"What's happening in London is epochal," Boys Smith says. "Never before have we built at such mass before." This has been created by a perfect-storm scenario: supply constraints, high land values, softened planning, the need to create growth, and overseas investors.

What's more, the normal restraints on developers are fatally weak. Local authorities, once the key constraining force, are so cash-strapped that they need money from Section 106 agreements, the part of planning law that requires developers to provide amenities (and which developers resist, by the way). "Also, developers often win on appeal on the grounds that they create jobs," Boys Smith adds. So if developments are deemed "viable" – that is, they tick the boxes – they're passed, or pass on appeal. Or, as in the case of Mount Pleasant, they're "called in" by Boris Johnson to ease their passage past sticky local authorities. All in all, it's been a great time to get your tower through planning.

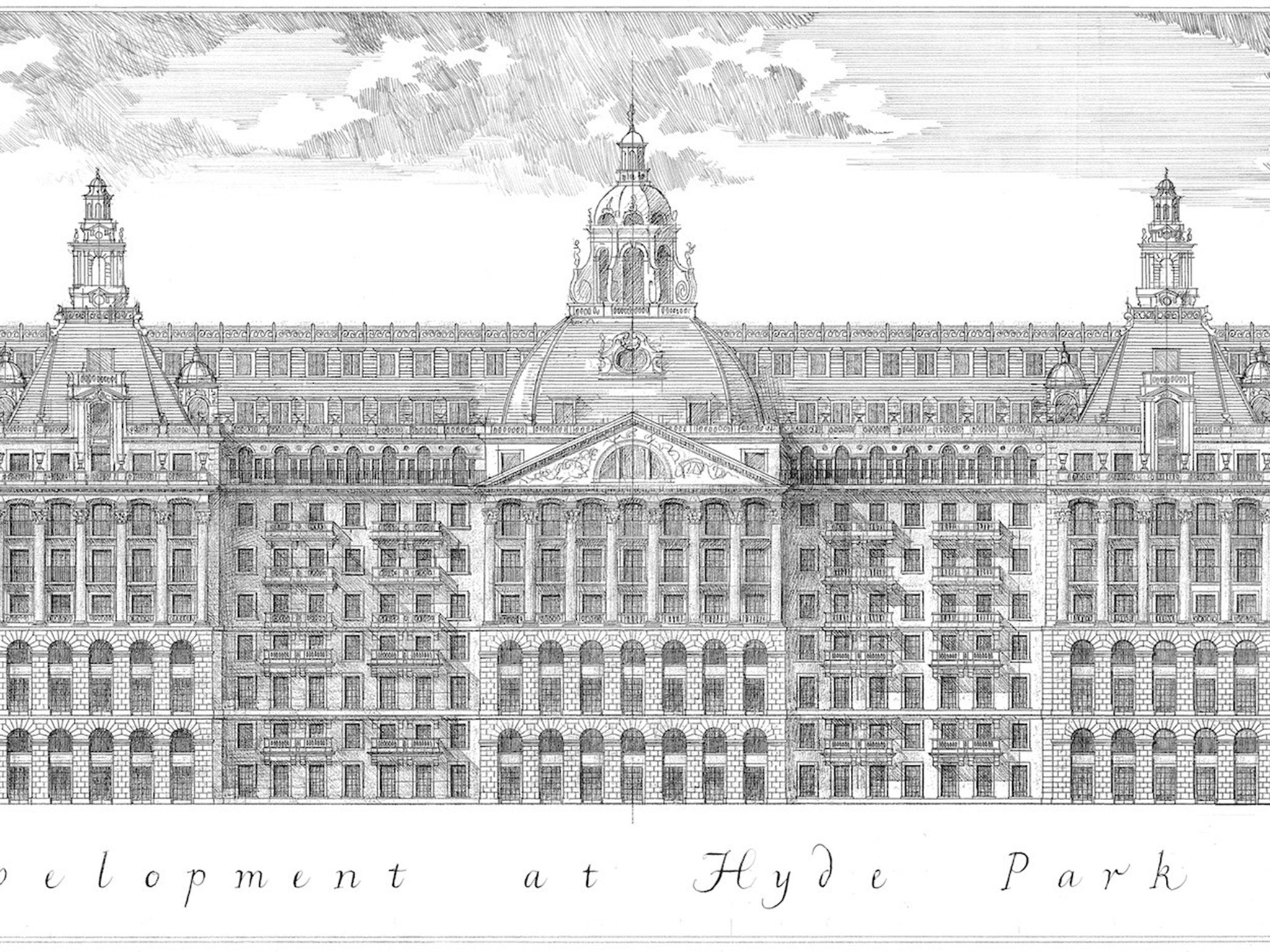

The distaste at London's cookie-cutter hi-tech has given Quinlan Terry's traditional ethos a new window of opportunity, and his firm recently designed an apartment block at Hyde Park Barracks in a kind of beaux-arts late-19th-century style – an extraordinary pinnacle, palatial approach that will no doubt revive all the Prince Charles vs Lord Rogers blather of a few years ago. But of course, Lord Rogers' company, Rogers Stirk Harbour, is known for One Hyde Park, the urtext of oligarchical investment-housing, while Francis Terry aims to counter what people are sourly and routinely calling "Dubai-on-Thames". "Architects say that they don't want Dubai, they want Paris," Francis Terry says. "So why do they build Dubai, and why do planners let them?"

It's a point, but couldn't the inclusion of the Terrys revive the 1980s Cold War between classicism and modernism? Well, yes, but this time round, the debate is informed by different factors. Speculative towers for rich investors unite Fogey and Progressive in opposition, driven on one hand by the squeeze on affordable housing and the visible expression of inequality; on the other, by their oppressive ugliness.

As if to illustrate how the mood music has changed, two absurd marketing films for Redrow London and the Berkeley Group's One Blackfriars, both featuring young high-net-worth types flitting between panoramic penthouses and art galleries, were both pulled in a matter of days following ribald mocking from social media, despite being obviously expensive productions. "We need change at a national level," says Boys Smith, who identifies several points of change. "First, the planning system hasn't been updated to reflect the engagement people expect, and often controls process, not quality and design." Second, social media has enabled objectors to engage rather than shout into unaccountable black holes.

Other protest groups have emerged. Last year's find that there were close to 250 20-storey-plus towers planned in London, 80 per cent of them residential, led to the Skyline Campaign, founded last year by the architect Barbara Weiss and colleagues. "These towers create wind tunnels, have little infrastructure, maintenance will be a problem," Weiss says. "In 20 years, I'm convinced they'll look grubby and sad."

Another critical group is shortly to launch, called Reclaim London, and includes Edward Denison, one of the founders of the Mount Pleasant Association. "It's about making better places and strengthening communities, serving the needs of all," Denison says. Reclaim London aims to aggregate the discontent and alchemise it into a new vision for London.

Some now call for urgent oversight. "London has always been shaped and modified by regulation," argues the architect Ptolemy Dean, the star of television's Restoration. "After the Fire of London, an act was brought in to stop shoddy building, for example. London has always had restraint, as have other great cities, like Paris." These new towers are akin to "architectural leylandii", he rails: aggressive, invasive, leaching the soil upon which they grow. "And what possible future outcome can we have when the controlling element is overturned by ill-informed politicians? And if we need residential housing, why sell it to international buyers?" Just recently, for example, it was reported that overseas buyers, mostly investors, had bought 80 per cent of the homes in four Thameside developments.

Dean is equally concerned about rural communities. "Liveable towns are fewer and fewer," he says. "Developers cluster around attractive towns and devalue the thing they want. We've got a rampant pro-development agenda threatening to engulf historic cities such as Chichester." Dean lives near Wadhurst in Sussex, where "each village has been told it has to have a certain amount of houses. All developers know planning rules have relaxed. So along they come with 'design and access statements', talking sustainability and offering speculative suburban housing. They say it's what people want; well, it's what they're given."

So, the questions begin. Does the new housing-design panel show the Government responding to criticism, or a Johnson-Cameron fault line? After all, many expected that Boris, an avowed classicist, might have been full of the joys of the Forum and the Agora. Perhaps his hands are tied. Even as he granted planning consent for Mount Pleasant, the Mayor asked for Francis Terry's "beautiful" alternative plans to be submitted as well – they are now being developed as part of a Neighbourhood Plan, enabled by the Localism Act. Labour's David Lammy and Tessa Jowell (now Labour's mayoral candidate) back the Skyline Campaign, while Betty Boothroyd and certain architects including David Chipperfield are supportive. A cross-party consensus is growing, reaching into Government, with the aim to change planning policy for the better, with two key deadlines: the general election this May and the London mayoral election a year later.

In the dissenters' shopping basket is a plea for long-termism, more community involvement, specific changes to the London Plan and national standards to end what Boys Smith calls "the bias against traditional streets". It's a positive agenda, he insists, with the ability to create better liveability, more civic meaning, more active communities and even (if that's your concern) better long-term investments.

And what if the prices fall, or the mansion tax makes a difference, or a future government and Greater London Authority changes the planning regime? All possible, and it's highly likely that the current market will depreciate and start to cure what Boys Smith terms "architectural elephantiasis". It'll be too late for the skyline, sadly, but this nimby still hopes that Mount Pleasant can be rescued.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks