Artes Mundi: Why can't the Turner Prize be more like this?

The Cardiff-based art prize is teaching the more famous award a lesson

Does the UK need another prize?

We have many prizes for literature and they have constantly been redefining themselves. Their aim is simple – to sell more books and raise the profile of the writer. Art prizes seem less purposeful. The Turner Prize was set up to raise the profile of contemporary art – and has already gone through several iterations – but it now has restrictions an age and nationality, which in these days of globalisation seem increasingly parochial. Cardiff’s Artes Mundi sets no such barriers. Now in its sixth appearance, the £40,000 prize is the highest for art in the UK. The prize attracted more than 800 entries this year. Any art professional can nominate an artist of any age and any nationality.

This is Karen MacKinnon’s debut as the director of the prize. Previously a selector and based at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, MacKinnon has spent her entire professional life based in Wales where she was born. She has the knowledge of her constituency and the palpable desire to bring her audience the best that can be found on an international stage.

This year she decided to expand her partner organisations and spread the exhibition over three venues. The Ffotogallery at Turner House is in the small town of Penarth close to Cardiff. With its beautiful harbour and pier, the small and perfectly formed venue is home to the work of two artists: Croatian Sanja Ivekovic and Icelander Ragnar Kjartansson. Ivekovic, a well-known artist in international circles, deals with major issues in a feminist context. During the past 40 years she has taken on the tumultuous stories of people and power and their shifting roles in a provocative and sometimes humorous way. In The Disobedient, a cabinet of labelled stuffed donkeys face texts on the people they represent, with empty shelves testimony to a work always in progress.

Upstairs, Kjartansson’s video The Visitors confronts the viewer. Kjartansson often works in a collaborative fashion and here we are at Rokeby Farm in upstate New York. The group of Icelandic musicians came for a week to live together and to rehearse a song – a testimonial to the end of Kjartansson’s marriage. They had one take to capture it; each musician inhabits a separate channel and screen. It is a poignant film, set to the words of Kjartansson’s ex-wife – and the music of participant sadness falls over the musicians. Each is alone until the end where they come together, Kjartansson rising from the bath where he has been playing, and join together to march off into the sunset. If it sounds corny – it is not. The rooms are lit and framed as if a painted tableau; this is a work speaking of the human condition, drawn straight from the heart.

The next venue I visit, Chapter, has a completely different constituency to Turner House. In a racially diverse area, it was started as the ICA of Cardiff. It is a hub for the community, with its well-frequented café and theatre – when I arrive in a quiet time of year it is heaving with families. Artes Mundi’s candidates here are the American Sharon Lockhart, Dutchman Renzo Martens, and the only British entries, collaborative duo Karen Mirza and Brad Butler. The British pair have colonised the café with Milk Snatcher, large colourful posters of Margaret Thatcher accessorised with a graffiti Hitler moustache.

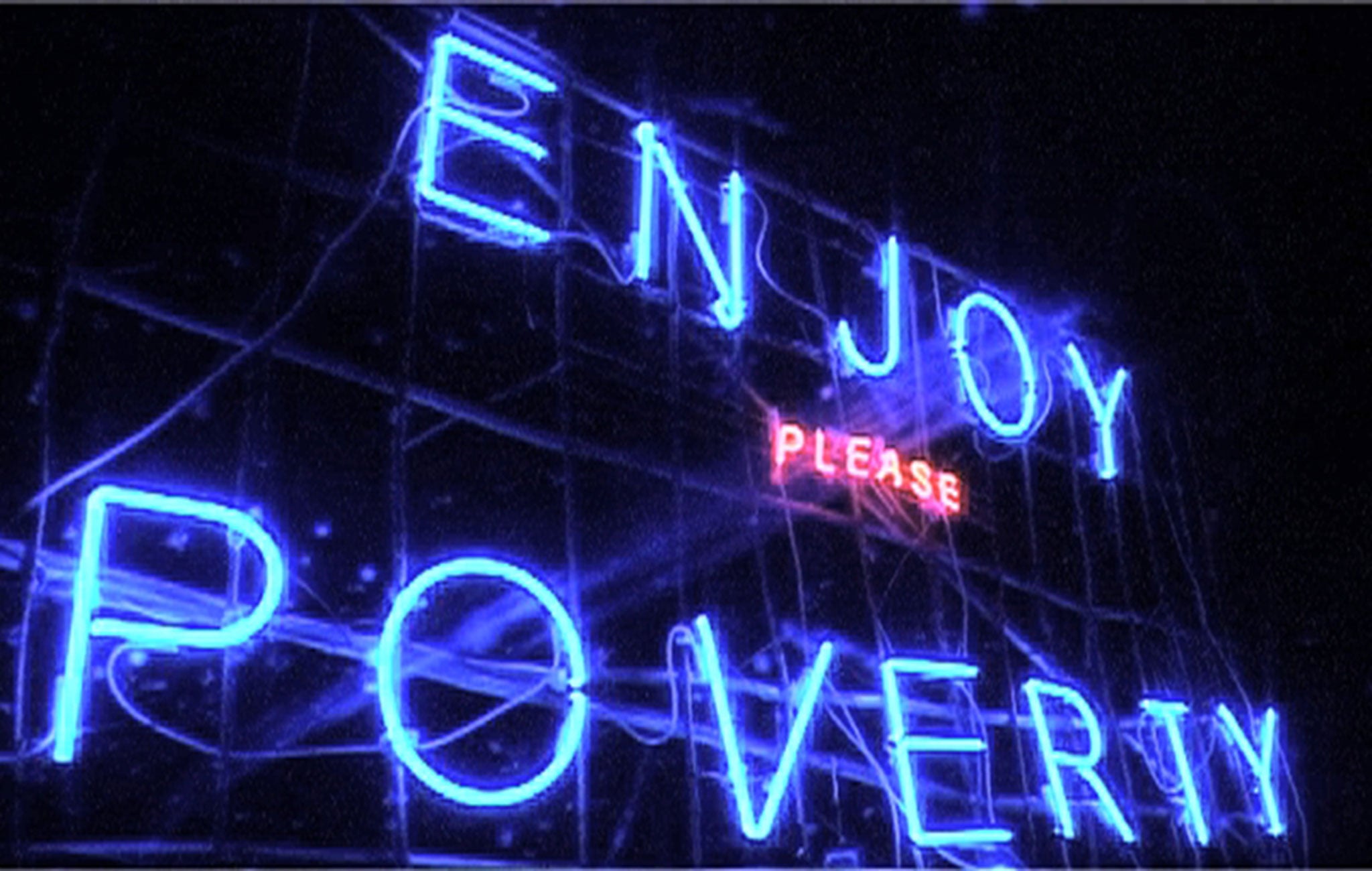

Martens has hung a large photographic work on the outside advertising his presence within the space with his compelling and politically incorrect video from Congo where he spends much of his time, having recently moved his young family there. What ties all the works together is the “human condition”, and Lockhart, with her workers' possessions from the Bath Iron Works in Maine, chosen as singular objects of America's working community – portraits of working men and film of workers exiting after a day’s toil – taps into the physicality of work, the universal and particular.

MacKinnon, who is taking me round the exhibition, says the challenge of working with a group of international artists is keeping the exhibition in balance – allowing them all their separate spaces and giving the opportunities for conversations to develop between their works. The Unreliable Narrator, a video piece by Mizra and Butler, is a hard pill to swallow – focusing on terrorist events in Pakistan; next to Lockhart, it is a tough ask for a young, family-based constituency.

The National Museum of Cardiff is a mixture of everything from dinosaurs in the basement to the contemporary collection – I suddenly find myself facing the beautiful painting by Michael Andrews of Ayers Rock opposite a fine Graham Sutherland. In the middle of this, the new contemporary galleries are home to the remaining Artes Mundi participants. Here is the challenging work of American Theaster Gates, a video of a gospel singer, and, as is his norm, objects from Dorchester, a deprived community near Chicago. Gates has become widely collected and has created an ecosystem where money made from his sales is poured back into his community. It may be a small ecosystem but it is a powerful one. The objects, including a toy goat upon a track and a disconsolate sculpture from Mali still in its packing case with its do-not-touch sign hanging disconsolately, bring instantly an exotic culture into the museum.

In close proximity is the painterly work of Portuguese-born but Spain-based Carlos Bunga, a simple yet sophisticated architectural intervention, Exodus. Towers of cardboard and masking tape form a pillared cloister with small side chapels, creating small sculptural-paintings rendered in cardboard with jewel like-colours. It reminds us that museums are often the chapels of contemporary life. This leads us to the last three artists: Martens, Brazilian Renata Lucas and Israeli born, Berlin-based Omer Fast.

Martens’ The Institute for Human Activities questions colonialism, with clay self-portraits produced by Congolese people used as moulds for Belgium chocolatiers – Callebaut (branded here on the wall). It is both challenging in its material and subject of Belgian colonisation.

Lucas is best known for her disco-like flashy floors. Here, Falha is a far dourer installation – sliding wooden panels that are heavy and dangerous enough to need intervention by trained workers to manipulate them. They create a soundscape that punctuates the intensity of Fast’s extraordinary film Continuity (2012). The film, beautifully acted, concerns a German family whose son is returning from war, and at first appears straightforward as they drive to collect him from a provincial station. Yet it soon becomes obvious that this is no ordinary homecoming.

So what do I learn from the Artes Mundi experience? The international quality is apparent in looking at the previous list of winners – Xu Bing, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, NS Harsha, Yael Bartana and Teresa Margolles, and the acquisitions – Mauricio Dias and Walter Riedweg, Lida Abdul, Mircea Cantor, Olga Chernysheva and Tania Bruguera – show the courage to acquire not just from the list of winners.

Organising 10 international artists to commit to come to Cardiff and do site visits and to return to a conference prior to announcing the winner of the prize is a huge challenge. MacKinnon and her team have risen admirably to it. She tells me that the opening had attracted a large audience, including Nicholas Serota, and one hopes they have learnt some lessons. Serota, in particular, should be thinking hard about the reinvention of the Turner Prize – 2014 was the least interesting for years, and I challenge most people to actually recall who won. Any one of these artists in this prize is a worthy contender for a solo exhibition in the Tate. Let’s give Ragnar Kjartansson a show in the capital and allow his team of far from merry music makers to touch a tenderness in our hearts.

The winner of Artes Mundi 6 will be announced on 22 January. The prize is at National Museum in Cardiff; Ffotogallery at Chapter in Cardiff; and Ffotogallery at Turner House in Penarth (029 2055 5300) to 22 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks