Paros' traditional fishing boats - and the men who helm them - are disappearing

They sit for days in harbour, drinking coffee, awaiting the right wind. When it blows, they set sail, to fish. But for how much longer? As the photographer Christian Stemper discovered, these grizzled Greek 'wolves of the sea' and their traditional kaiki boats are slowly disappearing from the waters around Paros

For the past five years, Christian Stemper has been documenting the fishermen who ply their trade on the Greek island of Paros, which lies to the west of Naxos in the Cyclades group nestled in the Aegean.

The Austrian photographer has been visiting the isle for two decades, and in that time he has seen the number of traditional boats – known as kaiki – dwindling: since 1995, overfishing in the Mediterranean has prompted the EU to provide the Greek government with funds to pay local fishermen to destroy their boats and turn their backs on the sea and an ancient tradition.

"This is not their fault, it is the fault of the big industry trawlers, which can still go out and fish – and it is killing off the small fishermen," says Stemper.

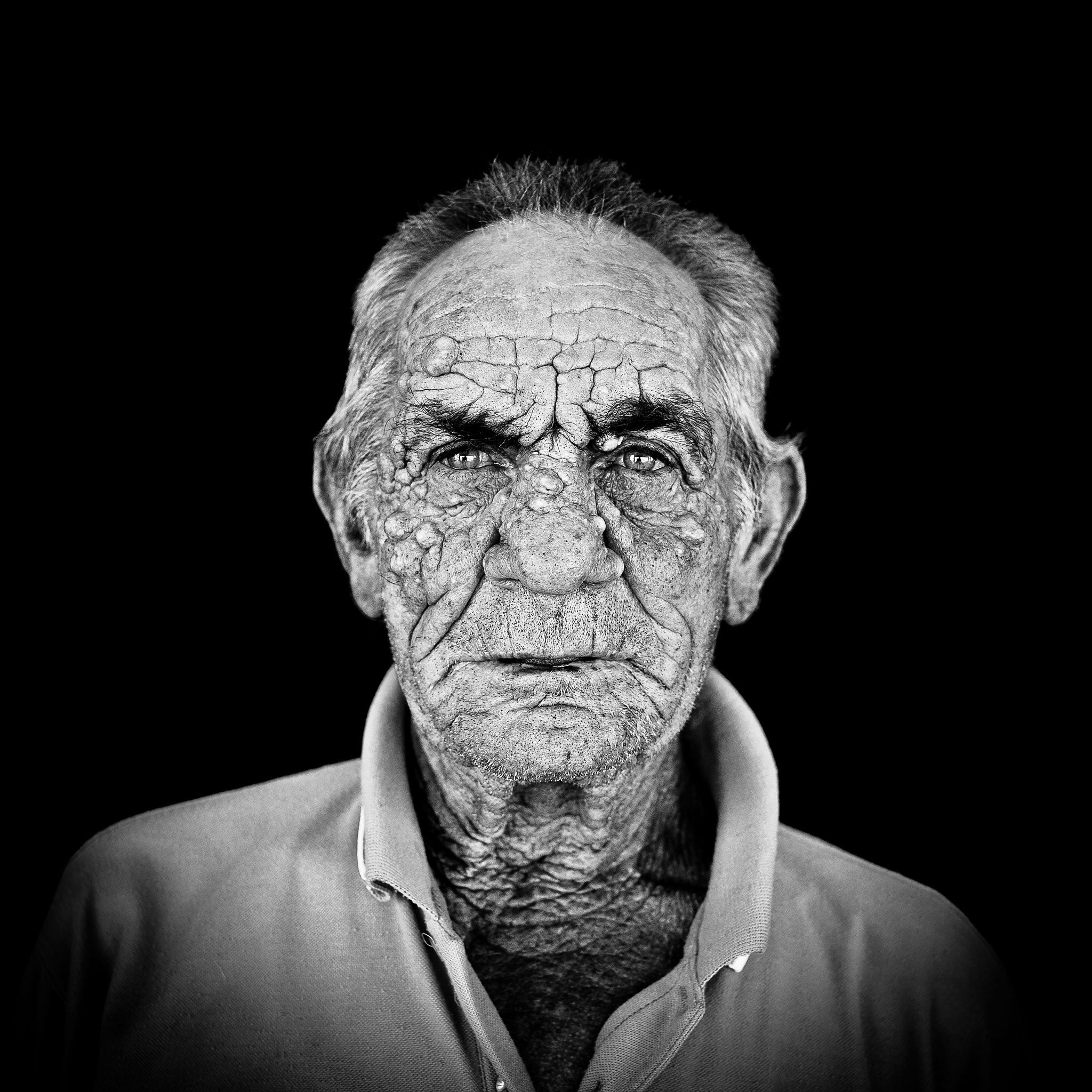

In his series of photographs, which he has collated in a book called Lupimaris, striking portraits of the fishermen's weather-beaten faces are seen alongside overhead shots of their boats and their day's catch. "I started with the boats then I got to know the fishermen and realised that they, the man and the boat, go on this adventure together," says the 44-year-old. "I wanted to make it a round story: the fishermen, the boat and the fish."

The images of the fishing boats' decks are as revealing and intimate as the frank black-and-white portraits of their owners. For Stemper, "The character of the fishermen shows on the boats – some are messy, some clean, just as some of the men are extroverted or introverted."

The destruction of the kaiki has meant that there has also been little demand to preserve the traditional craft of boat-building. "I interviewed one of the last boat-builders in Paros," says Stemper, "and I wanted to photograph his boat blueprints. But I couldn't because, as he said, 'I have it all in my mind.' He almost started crying because when he passes away, there will be no one who can build these boats any more."

Stemper's time on Paros meant documenting a livelihood on the ebb, and also a disappearing tribe of men, whom he nicknamed "Lupimaris", meaning "Wolves of the sea". He held an exhibition of the work for the fishermen. "I wanted to show them the photographs and give each of them a portrait of themselves. Their families, wives and children came, but only one of the fishermen showed up. They have a special mentality; they don't care about anything else: just the sea, the boat, and whether they can go fishing."

Stemper feels a strong affection for the fishermen's approach to life. "They sit for three days on the harbour, drinking coffee and waiting for the right wind. If there is no wind, they have all the time in the world, and if there is wind, they go fishing. Time has another meaning to them. They reduce the speed of time. You can see this satisfaction in their eyes. They are happy, like children, even if they are 70 years or older – they have done all their life what they wanted to do."

To buy the book (€49), prints and postcards: lupimaris.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments