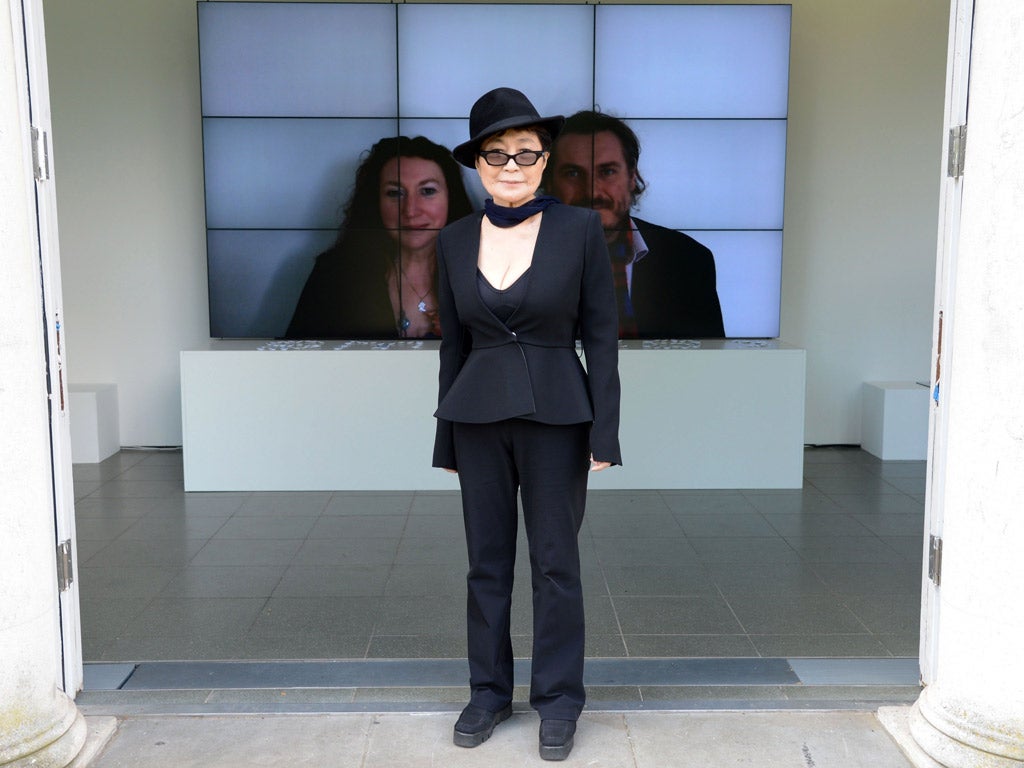

Tom Sutcliffe: Why unworldly Yoko Ono's pleas for peace should still be given a chance

There's an innocence and unworldliness to Ono's work that is distinctive

If you visit the Serpentine Gallery right now, you'll see a group of three small trees standing by the entrance, densely covered in luggage labels. This is a version of Wish Tree, a Yoko Ono work that invites passers-by to write their desires onto a tag and tie it to a branch. At the end of the exhibition, Ono collects the tags and she plans eventually to incorporate them in another artwork, as a concentrated accumulation of human yearning.

To date, she says on her website, she's collected over 495,000 wishes and she hopes that the work in which they're ultimately placed will "give encouragement, inspiration and a sense of solidarity" to a world filled with fear and confusion. She also says that she never reads the wishes, which is fortunate really because it means that she won't see the one on which someone has written "I wish Yoko Ono would stop doing things like this".

Wish Tree is a very typical Yoko Ono artwork. It's so hippy-dippy in its attitudes that you can virtually smell the patchouli oil. It's also, while being unavoidably twee in conception, quite cleanly decorative in appearance. Looking at those trees from a distance, you don't see what becomes apparent when you get closer and actually read the individual labels: a whispered Babel of need and regret and hope. You see a Martha Stewart table centrepiece, the sort of thing that a stylish hostess might run up for a big dinner party. Most typical of all though – this is an artwork that leaves itself open to attack. If Ono genuinely didn't anticipate the odd cynical or sardonic contribution to this piece then she's so trusting of human nature that she probably shouldn't be allowed out without a carer. But of course she will have done, and she made it anyway.

There's another, far better work in this show which, while less vulnerable to attack itself is about vulnerability. It's one of her more famous performance pieces, Cut Piece, in which she kneels on stage and allows members of the audience to snip portions of her clothes away. In the Serpentine show two video recordings of Cut Piece face each other across a gallery, one filmed in 1965 and the other in 2003. It's intriguing to see the differences in attitude of those two audiences, one still getting to grips with the conceptual in art, the other positively blasé about it. But in both, Ono herself is at first metaphorically exposed and then literally so. Some participants are respectful, even protective. Others rather aggressively go straight to the point, like the man who seizes the fabric over her nipple, pulls it out to a taut cone and snips a circular hole.

All art is vulnerable to an audience's scorn, of course, and conceptual art particularly so. But there's an innocence and unworldliness to Ono's work that is quite distinctive. To say that it wears its heart on its sleeve doesn't quite do justice to its considered naivety of utterance. War is bad and I don't like it, says more often than not, and it then makes no attempt whatever to conceal the fact that nothing more complex is going to be added to that statement. It almost dares you to mock, and it has to be said that in quite a few cases the invitation is difficult to resist. There are pieces here that are banal and fey. But there's also a kind of nerve in the face of those who always seek to complicate simple truths. I thought the show was wildly mixed. But I also had a strange impulse to write out a tag reading, "I wish I wasn't always so critical".

Citizen Bryn's fantasy role

The revelation from Bryn Terfel that he hankers after someone to write an opera of Citizen Kane so that he can sing the title role was a nice instance of the fantasy work of art – one of those thumbnail daydreams that immediately starts you thinking about what it might look and sound like. Obviously there would have to be a "Rosebud" aria, but who would sing it, given that the final revelation of the film is a voiceless image? And how would they cope with Susan Alexander and the humiliating moment at which her musical frailties are finally exposed?

Cover stars begin a new chapter

Intriguing to see that Richard Russo has joined Stephen King in announcing a dead-tree-only publication for a forthcoming book. King said he was doing it out of nostalgia for the paperback format. In Russo's case, it looks to be more of an art-book affair, offering a platform for his daughter's illustrations and his son-in-law's book designs. And in both cases the story resulted in news coverage that these publications would otherwise not have received. I don't suppose that effect will be endlessly repeatable but authors can't be unaware of another advantage to real book publication that actually increases with every e-reader sold. E-books are faceless. And the more there are of them the more noticeable a real book becomes, turning its reader into a human billboard. In the kingdom of Kindles, the guy with his name on the cover is king.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks