Degas, Edgar: Bellelli Family (1858-60)

The Independent's Great Art series

The librarian's great distinction, between fiction and non-fiction, doesn't apply to paintings. The best stories often appear in the most factual forms. The nearest pictorial thing to the 19th-century novel is the 19th-century portrait.

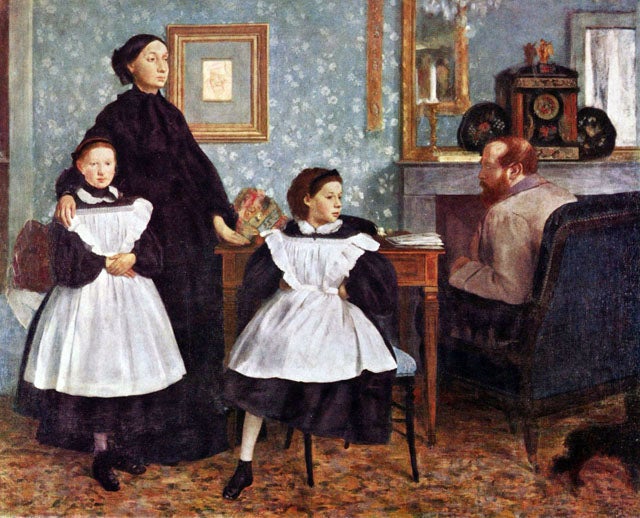

In Degas' The Bellelli Family, the main sitters are his aunt, Laura Bellelli, née de Gas, and his Italian uncle, Gennaro Bellelli. With them are their pre-pubescent daughters, Giulia (left) and Giovanna.

On the wall behind there's a fifth family member. It's one of Degas' own drawings, a chalk study depicting Laura's father – and his grandfather – Hilaire de Gas. (Degas had compacted his aristocratic surname to be a proper bourgeois artist.)

The Bellelli family are arrayed in something like a row. But this is a portrait where the facts of the sitting are not taken for granted. No, the way the subjects deal with the predicament of being portrayed, their sitting behaviour, is the way they reveal their characters.

Or at least, that's what the picture pretends. But the scene is too telling to be true. Degas surely has arranged them, and turned the Bellellis into a diagram of family relationships: power, conflict, genetics, upbringing. In his staging and design, he lays them out with an almost fairy-tale clarity.

The mother, Laura, is the dominant figure. She stands severely upright, engulfed in black, head high, face set – and beside her head, half over-lapped, there's that drawing of her father.

This old man's image presides over the group, and his daughter, Laura, faces in the same direction, carrying on the line. Despite the married name, it is the house of de Gas she presents to us.

Her husband, meanwhile, lurks almost out of the frame. So far as it's possible in a picture that shows only a room, he is a man who has retired – or been expelled – to his den.

He won't get up. His body is turned away from the front. Barricaded behind armchair and table, he does the very minimum necessary to appear in his family group – leaning round, peering, offering his profile on sufferance.

Finally, the daughters: what a study in contrasts. Giulia stands, to the picture's side, hands folded, feet together, in her mother's shadow, merely a sub-section of Laura's great dark arch. Giovanna, on the other hand, is centre-stage and independent, half-sitting, hands on hips, one leg tucked up, in a fidgety, show-off pose.

And nobody, you notice, is looking at anybody. Nobody's eyes meet. Nobody is proudly or fondly gazing at spouse or child or sibling. And they don't have the excuse that they're all facing the front. Looks are simply averted.

It makes a difference if you know that there's a sixth family member present – cousin Edgar. Their reluctance to look at him adds a further dimension to the drama. Giulia alone faces out at the viewer/painter – primly, or maybe with a get-me-out-of-here expression?

As for who is her mother's true daughter, Degas points clearly at Giovanna. Look at her face, and at Laura's: it's the same face, the same hair shape and colour, the same expression, the same three-quarter view of the head. A diagonal line of descent passes between these two strong characters, while the two outside characters, Giulia and Gennaro, linked by their reddish hair, are the weaker parties. But what makes it such a true family portrait is that, just looking at it, you find you're taking sides.

The woman is clearly a tyrant. The man is clearly impossible. Giulia is a little miss. Giovanna is a brat. Somebody is to blame and somebody's going to suffer. It's an acute psychological study, not just of the Bellellis, but of the viewer. Ask someone to tell you about Degas' Bellelli Family and they'll tell you all about themselves.

The artist

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) is a much more serious proposition than his old reputation as the Impressionist of human action, doing race meetings in bright livery and blur, graceful ballerinas on the hop in a flourish of tutus, and lively café-concerts. His portraiture and work-scenes have a novelist's sense of how the self is shaped by its social existence. And for making a drama out of the body itself, its strains and toils, as in his bathers and towellers, he is the modern Michelangelo.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies