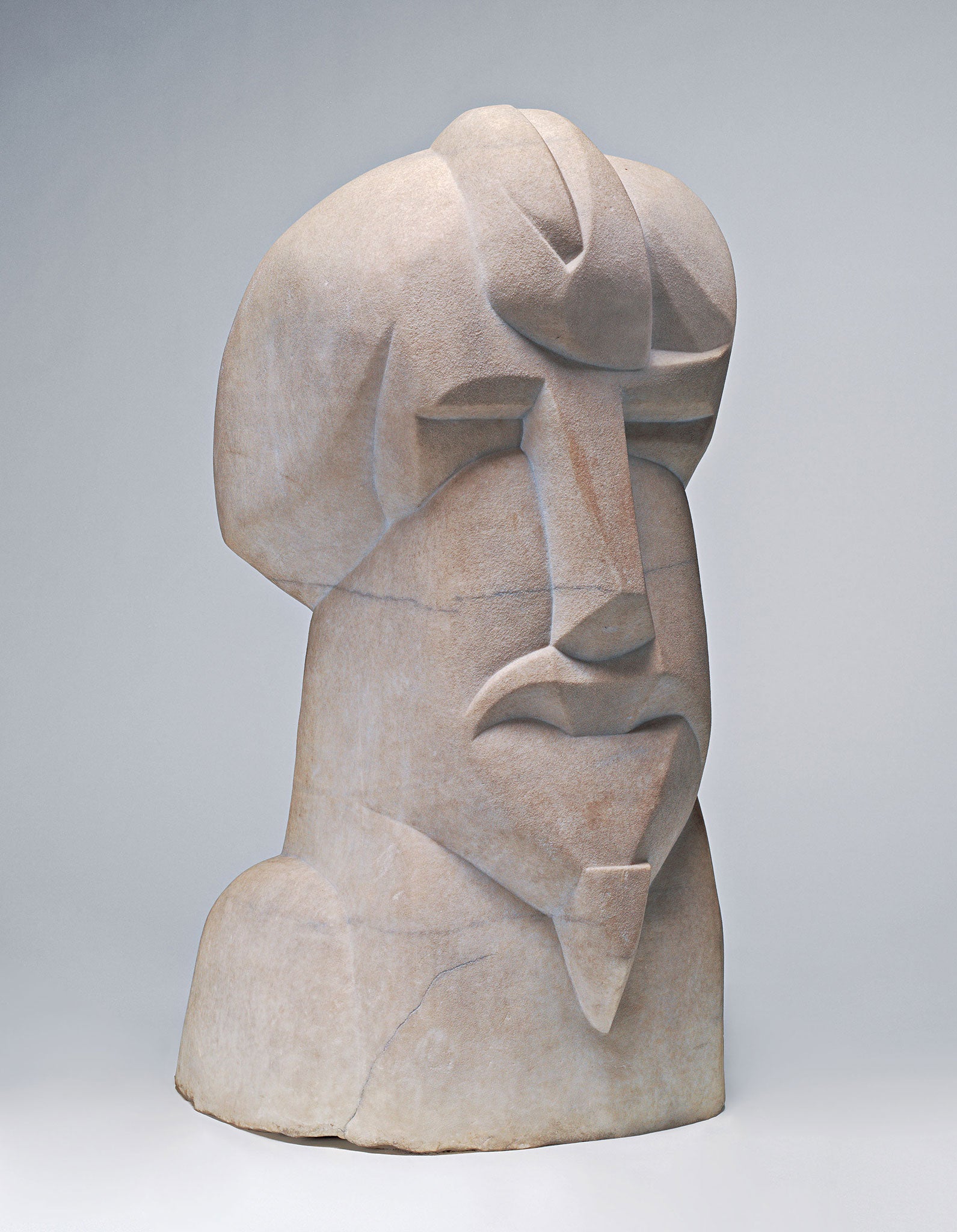

Great works: Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound (1914) by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Poets are an odd to lot to characterise. No one quite knows what a poet is, not exactly. They can inspire reverence, awe, and even a touch of fear in the soul of the English teacher who does not exactly get on with – or even much understand (if the truth be known) – poetry. If you were introduced to a poet at a party, what would be your opening gambit? Is a poet a bit of a seer, a bit of a memorialiser of the race? Certainly was, in days gone by. Think of Homer. Think of Blake. Is he also perhaps a healer of sorts, a doctor of the soul? We are often inclined to reach for a poem at a funeral.

And what about the look of poets? Tennyson sported a tremendous, moons-of-Saturny, broad-brimmed hat, and when GF Watts, memorialiser of so many of the great Victorians, came to sculpt a full-length portrait of his old friend in the company of his faithful dog Sirius (the one that used to pull the cart containing the various brothers Tennyson around the Lincolnshire Wolds), that hat played a large part. The right hat sets off, adds mystery, gravitas. It also part-conceals. Alas, that great memorial to Tennyson now sits in a park in Lincoln, somewhat unloved.

And what of this strange portrait bust of the American poet Ezra Pound, who bounced into London, knowing no one, in 1909, yawping twenty to the dozen, and desperate to meet WB Yeats, the greatest living poet then writing in the English language? Pound soon made his mark, as poet and literary impresario.

There are so many versions of Ezra Pound. He wore so many different masks, in poetry as in life. We have on the one hand the austere magnificence of this Hieratic Head, sculpted in 1914 by a young French artist called Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Pound was 29 years old when it was hand-carved from stone, but its look is timeless. Gaudier did about one hundred preparatory drawings for this bust, of which 10 survive. Some of them are hard, swift and geometrical. The one that turned up recently in a house in Shepherd's Bush was quite different. It had a yielding softness about it. It seemed to linger over its subject. It showed us a young man of a quite specific age.

Not so this portrait bust. In this bust, Pound could be young. He could also be old. Like a representation of some god, he is beyond the reach of all temporal considerations. That is probably what pleased him so much about it. And it pleased him a great deal. When he decamped to Italy in the 1920s, it eventually followed him to a garden in Rapallo. He loved to be in its company. As he warmed towards the idea of Mussolini, the bust's stark lineaments probably nodded sagely, in quiet approval of his growing hysteria.

In short, the bust gives solidity to his character. It makes him more and other than he ever was. It raises him to a higher level. It sets him apart from all the rest. It puts him on a level with the gods. It monumentalises and aggrandises the man, simplifying his features until they are nothing but brilliant, hard facets. It tricks him out for all eternity rather as the Emperor August was so tricked out on those Roman coins of his.

Essentially, Pound has become so much greater than himself in this Vorticist portrait bust. Pound said that he wanted the portrait to look "virile", and so it does – to a degree (from the back it looks rather like a limp penis). And yet there is much more to it than virility. It is also a carapace or helmet of sorts. It has a kind of brute, martial vigour. It marches. It is always on the front line, beating the hell out of its curvaceous Perspex shield. For poetry's sake.

About the artist: Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915)

Henri Gaudier was the son of artisans from a small village near Orléans. His parents destined him for a life of commerce – but he thought differently. Art was his calling. After arriving in England in 1911, he struck up a curious, mother-and-child relationship with a Polish woman he met in a library called Zofia Zuzanna Brzeska. She was twice his age. She called him Pik, Pikus, Pipik; he called her maman, Madka, little Mamus. He tacked her surname onto the end of his. Thus was born the sculptor with the unpronounceable name. Pound tended to call him "Brzx" in his private correspondence. He was killed on the Western Front in 1915, at the age of 23.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments