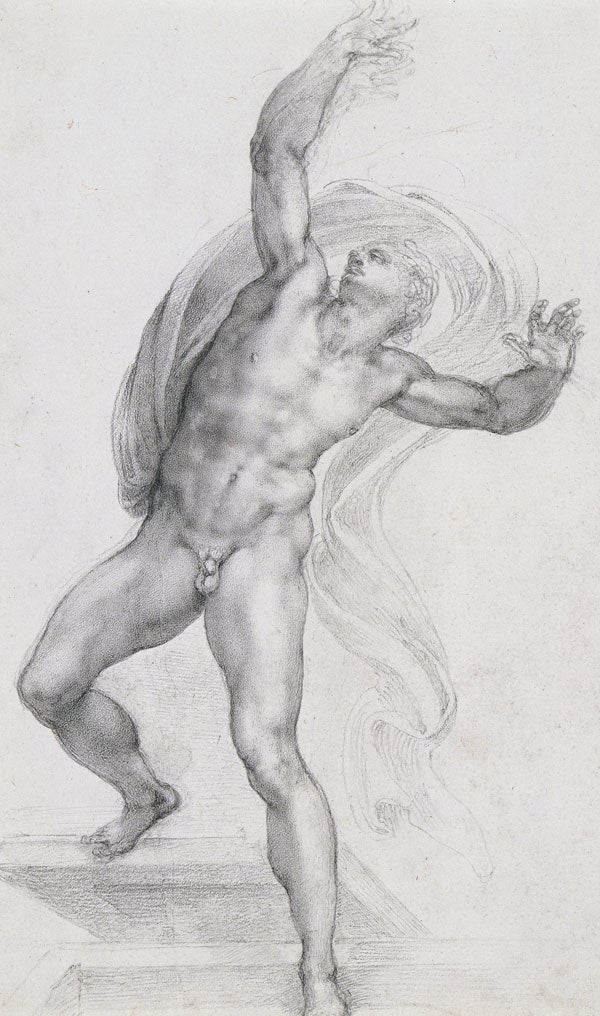

Great Works: The Risen Christ (c1532), Michelangelo

The Royal Collection, London

Football itself may be a beautiful game, but there are no beautiful pictures of football. It's a mysterious problem. Surely these scenes of human anatomy and action should be a glory. Surely somebody's creative genius should be able to match the genius of the sport. But for some reason there seems to be a mistake, image-wise, about the whole subject. Is it the unfortunate stripes? Perhaps. Or is there something odd about strikers, headers and savers – these figures that have added balls – that makes the bodies undignified? Perhaps too. One way or another, no satisfactory artistic solution has ever arisen.

True, there are a few possible paintings from the 20th century. For example, there is Henri "Douanier" Rousseau's naïve The Football Players (1908), showing four absurd moustachioed gentlemen, leaping around in elegant and striped pyjamas, and twirling up a ball. Alternatively, there is Umberto Boccioni's Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913), a tornado of pure Futurism, an energetic scrum of forms, though more or less unrecognisable as a form of human activity or anything else.

Or there is Max Beckmann's Footballers (1929). This is a scene with a very high format, often used by this painter, and piling up one sturdy body on top of another, with kicking feet, grasping hands, and suggesting a sport more like basket ball. Finally, and much later, there is the most bizarre tableau of William Roberts's Goal! (1968), a small group of wooden, clodhopping figures, which resembles a minor league event, though meant to celebrate the 1966 World Cup victory.

In short, the genre is hapless. You'll have to check up it, but no soccer painting has even produced a decent work of art. Two of these pictures are not even football subjects. They're rugby football subjects, though that doesn't really make much difference. We must simply accept the difficulty. There is no literal image worthy of the game. So, we must seek a more lateral image – and something triumphal, amazing, a physical action beyond belief, a miracle. Surely it does exist. In fact, there is only one possible artist and one possible subject.

Michelangelo's The Risen Christ is the greatest player. He depicts a supremely heroic body. But he's also deeply concerned with the construction and the malleability of the human form. His art has a power that is both exhilarating and alarming. He can do to this figure whatever he likes, put it through the most incredible twists and turns, displacements and distensions, make it into the most contradictory shapes. Limbs can go this way, while seeming to perform a continuous gesture. This is a form of drawing, which is also a form of training, which is also a form of sport.

This particular subject, the Resurrection, offers both opportunities and freedoms. The Gospels never describes the event. They treat it as fait accompli: the grave empty and Jesus already up and about. As artists often picture it, it looks like a firm and straightforward act of will – Jesus advancing out of the tomb with a strong leg to the fore, or levitating several feet in the air above it.

But when Michelangelo shows this act, you can't tell if Jesus is doing it, or it's happening to him, or what's happening exactly. It's a radically ambiguous art, that's bent on daring impossibility. The action of the figure is almost indescribable. It's a thoroughly complex articulation, combining a forward stride, a backward lurch, an outward fling and an upward yank.

The potential for triumph is there. One leg is planted firmly, vertically forward. The arms are ready for victory. But then this leg does a sideways tort, which aligns with the much less grounded other leg and the teetering torso. The left arm becomes a frantic attempt to regain balance, while the right arm, reaching straight above the head, seems to be pulled up by an invisible grasp. The reviving figure is staggered, disoriented, tipping over, struggling for equilibrium and self-control among these bewildering forces.

And as the body becomes deeply involved in its action, the story itself is less clear. Of course the setting is a tomb, not a goalmouth. One leg steps on a stone lid, the other leg is coming over this opening, and the body is emerging into life. But the tomb is shallow and very vague, and the figure's gestures can suggest other possible activities. He could be saving himself. He finds himself thrown in the midst of things. He could be catching out for something or pushing it away. His hands may be raised up. His stance may be ready. His body may have no certain focus, and he turns this way and that, but he has at least a powerful sense of quick response.

So this rising man is also a player. He isn't a solo agent. We may not be able to see any other figures in the picture, but look at his performance. His struggles are subject to surrounding forces. He's moving in a world of actions and reactions. This figure, in fact, is very clear: a man on a field of battle, armed only by his body, with a bar above him, and a danger rapidly coming towards him. Michelangelo has somehow imagined this modern ideal. Spot the ball? We can't see it until the last second. And then it happens. He is salvation. The unbelievable goalie.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments