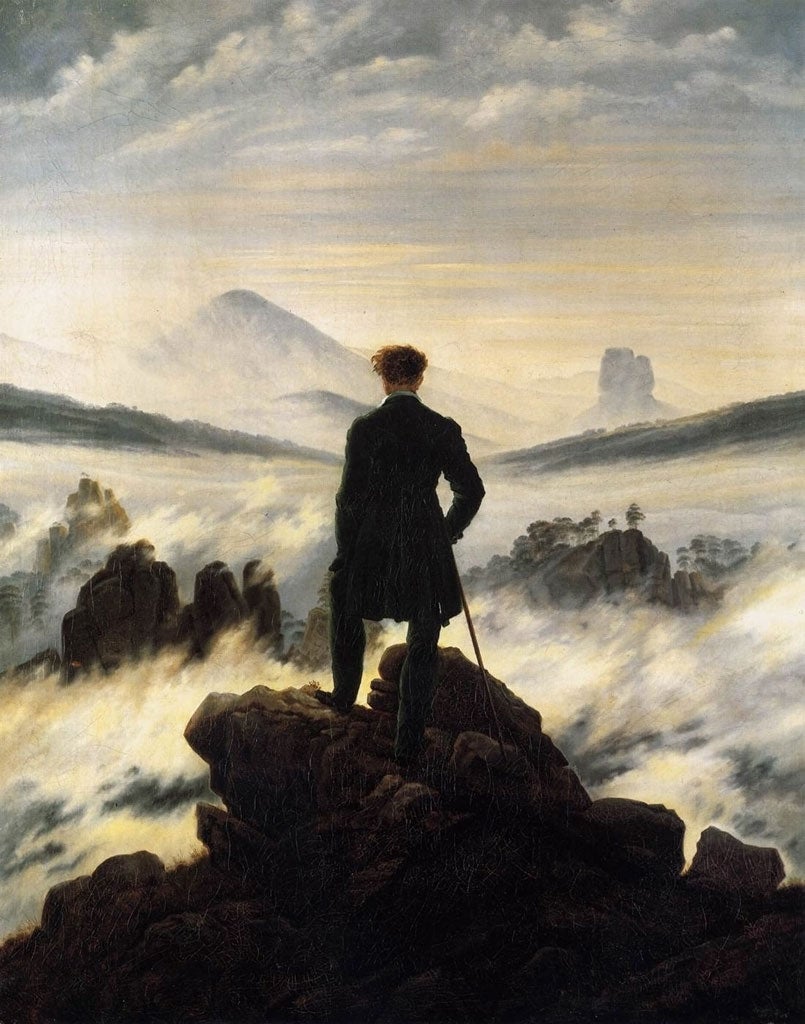

Great Works: Traveller Above the Mists, 1818, by Caspar David Friedrich

Kunsthalle, Hamburg

Call it the essence of the Romantic impulse it you like. Man, the eternal wanderer, stands alone in a landscape that he may even be calling into being.

He seems, with his cane and his frock coat, to be two things at once: the embodiment of the sheer imperiousness of man, commander and supreme explicator of the universe – see at what a great and commanding height he stands – who may be orchestrating this scene with his cane as if he were the conductor of Mahler's Seventh, and also to be utterly vulnerable in the teeth of the overwhelming muchness of the forces of nature. He is both god-like in his stance, and hopelessly overshadowed, vertiginous in his fragility and aloneness. Notice the unruliness of the hair on the top of his head. That is the only outward hint that there is wildness within.

He alone is nature's witness. Here he stands, on the very brink of self-knowledge and of a knowledge of this estranging – and self-estranging – Other that he can never know, except in part. (How can he hope to embrace that which he cannot truly see?) Perhaps the two are one. Perhaps this is what self-knowledge will in the end amount to... This is his burden. And his account alone will be its testimony. What he sees seems to give the lie to, and even render slightly ridiculous, his pre-eminent respectability. Beneath the trappings of his clothes, there is the inward seethe of his passions, intellectual or carnal, which seems to be reflected in everything that he is witnessing.

There is no one to share all this with. The only dialogue will be this rumination with himself upon all that this means, which may include some reflection upon to what extent this scene is perhaps a showing forth of all that he knows or does not quite know about himself inwardly. Is what he is seeing some kind of reflection of the creative turbulence of his mind, is this the truth of the inner man – or is he gaining some kind of inward quickening from all that he is surveying? How terrifyingly unruly and unknowable and untameable all this terrain is! How far does it stretch? How deep does it go? And what if he were to fall...

We do not know – just as, we suspect, he does not know – what exactly it is that he is seeing, what this mirroring of the self may amount to. It is much more vast than this mere man posturing here even as he teeters at the very edge of the crag – in fact, he is a bit of a homunculus here, smaller than man, against such a setting as this one. By even being here, we feel that he is presuming to outface or outwit or stare down – and all of these possibilities strike us as derisory. After all, and even though he may have chosen to come, he does not belong here. It feels absurd to have him here. He seems to have been wrenched out of his familiar social context, to have been beamed up to such dizzying heights as these –precisely in order to provide us with this image of self-estrangement. We feel that he stands here at a very unsettled moment in the creative process. Creation groans.

The landscape seems to be billowing away from us even as we look at it with him, like the waters of an ocean rising and falling. How high are these peaks? How deep are the valleys that may lie beneath this dulling, muffling blanketing mist? The seventh day is a long way distant, we feel. We do not know what we will see when the mist lifts. That is part of the painting's tension, that everything is yet to be revealed, and that we cannot quite believe that it will never be revealed. Notice how the slope of his shoulder follows exactly the line of that distant blue peak, and how the mossiness of the texture of his clothing seems to blend, tonally, with the landscape. It is as if the shape of his own body and the fabric of his clothing are somehow complicit in this vast act of making. He is also perhaps contemplating the turbulent depths of the inner man, and reflecting upon the fact that there is no telling how far we can range if we apply our imaginative faculties to the utmost.

About the artist: Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

Caspar David Friedrich was a leading German Romantic painter of his generation who first studied in Copenhagen and later settled in Dresden. He had a predilection for scenes of an almost chilling loneliness and sublimity, in which the human element is cowed into submission and almost overwhelmed by the overbearing grandeur of nature in all its unknowable immensity, all stark, craggy bleakness, complete with the most mysterious of lighting effects. If with a childish adult, hold its hand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments