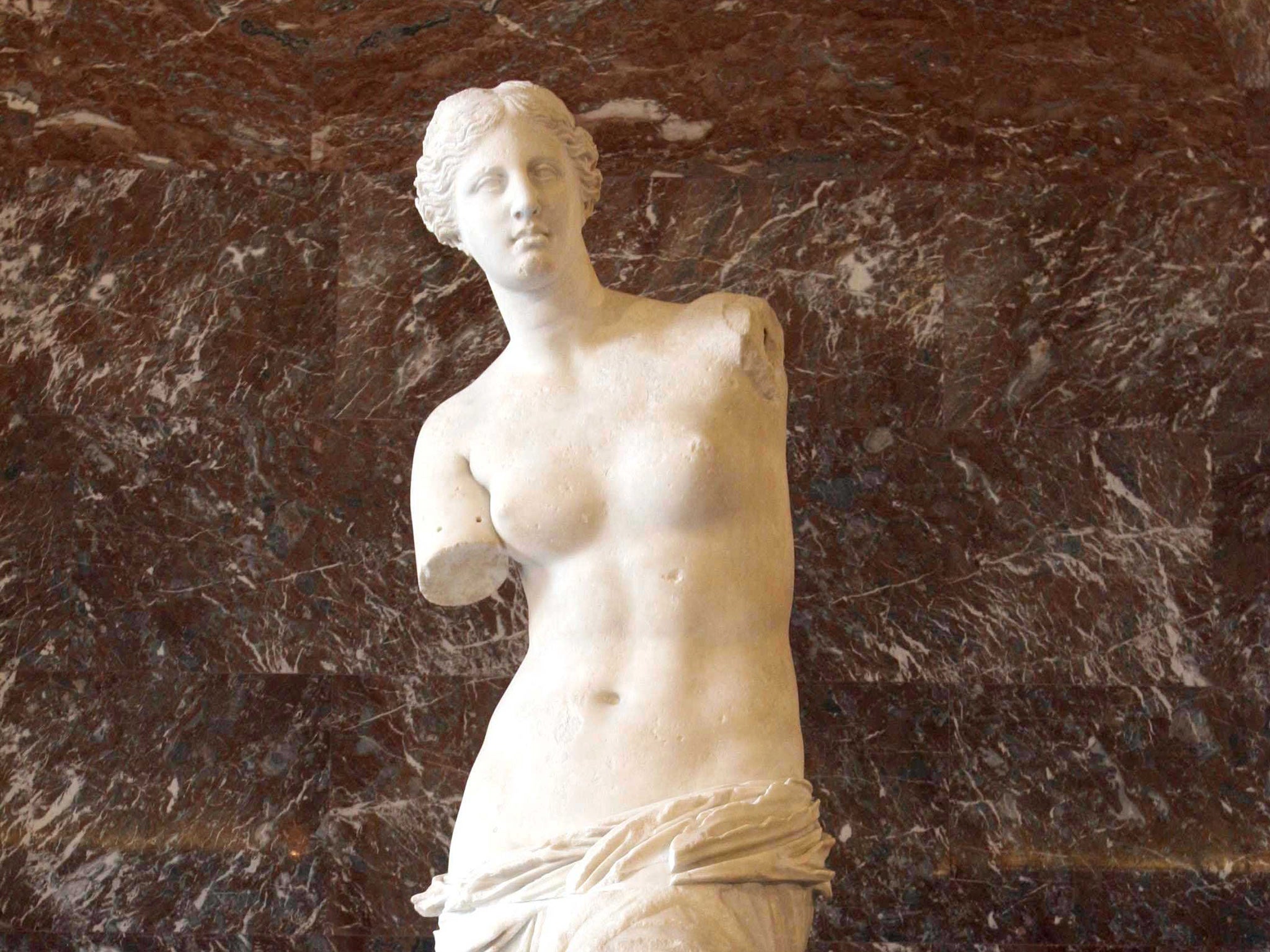

Just what was the Venus de Milo doing with her arms?

3D printer tests the hypothesis that the 100BC statue was originally spinning

It is one of the most recognisable representations of a woman in the history of art, but the Venus de Milo leaves one question unanswered: what exactly was she doing with her arms?

The ancient Greek statue, which was created before 100BC and depicts the goddess of love Aphrodite, was rediscovered in 1820 but the mystery of what her upper limbs looked like and how they were lost has long baffled archaeologists and critics.

Now the American writer Virginia Postrel has worked with artist and 3D sculptor Cosmo Wenman to try to solve the puzzle – with the pair making a convincing case that she was originally depicted spinning thread.

Critics had previously imagined her to be holding a mirror or an apple, or perhaps even cradling a baby. At the turn of the century some artists preferred to interpret her form as a sculpture named Victory, holding a shield on her left thigh – or even using this as a mirror and admiring her own reflection. But the question was never satisfactorily answered.

“She is a puzzle, gazing serenely at something we cannot see, something once held, we assume, by her missing arms,” Ms Postrel said. She worked with Mr Wenman, an expert in 3D printing techniques, to test out her own theory that Venus was spinning yarn, an activity which had an association with sex in Ancient Greece.

“Greek vases depict prostitutes spinning. It was a productive occupation while waiting for clients,” she said. “A spinning Venus seems theoretically plausible, but would the pose actually work? In the 19th century, a sculptor might have tested the idea with a plaster cast. In the 21st, we have a cheaper, simpler, more versatile option.”

So Mr Wenman recreated the sculpture – complete with arms in a spinning pose – using 3D printing tools. He worked with sketches, ancient images of spinning, a YouTube tutorial on how to drop a spindle and a digital version of the sculpture’s anatomy to extend the existing post.

The project produced the very first 3D digital survey of the world-famous statue, which is now freely available. After a few attempts, a printed plastic model was made, and Mr Wenman also fashioned spinning thread to fall through the statue’s arms.

“I figured that the ball of wool on the distaff would be too heavy to have been made in marble, so I painted it gold as though it were wood, or a hollow, gilded bronze sphere,” he explained. “The thread would probably not have been wool in an actual life-sized statue, so I used a gold chain instead, and carried the gold motif down to the gathered thread of the spindle.”

Ms Postrel conceded that their project did not prove that the Venus de Milo was originally a spinner, but said the results were “convincing”. The modern sculptor agreed: “Spinning thread seems to me to be the only activity that actually requires this odd, specific pose,” Mr Wenman said.

The Venus de Milo, which is generally credited to the Greek artist Alexandros of Antioch, is on permanent display at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments