Alice Neel: Painted Truths, Whitechapel Gallery, London

An artist who's good for the soul

The American painter Alice Neel, who died in 1984, described herself as a collector of souls, and there's no doubt that when she painted a portrait, she was painting far more than a body and face. Something, which seems to come from the sitters, quivers shakily on her canvases – painted eyes and hands often seem to wobble unsteadily. Groups of sitters, families and couples, don't seem to be connected to one another.

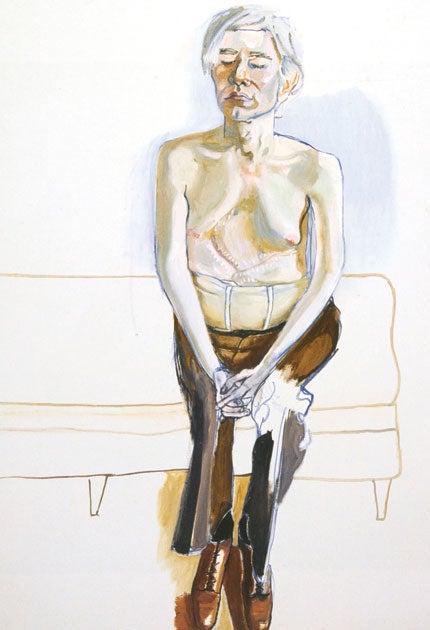

While Neel's contemporaries and friends in New York, where she lived, were making abstract painting or pop art, she stuck doggedly to painting portraits throughout her life, capturing not only the city's artistic milieu of which she was part, but bundles of fragility and uncertainty within it. Andy Warhol (1970) is probably her most famous portrait here. Remarkably, Neel convinced the artist, who was highly sensitive about his body following his gunshot wounds, to pose without a top on, scars and saggy body revealed, with grungy pants pulled up high over his brown trousers. This is a very gentle portrait, however, with Warhol's pale face and hair appearing almost disconnected from his body, head tilted up and his eyes closed – perhaps he wanted to make sure Neel didn't steal his soul. His head and shoulders are surrounded by a pale blue glow, which is almost beatific. Another bright, revealing image is a painting of Neel's son as an adult. Hartley (1966) contains a full rainbow of colours, but it's the secondaries that stand out: green, purple, orange, framing her son, who leans back, hands behind his head. His face and body are chiselled, yet strained; he had returned home from medical school, unsure of his ability to continue seeing bodies every day. He is a study in the grey, greenishness of skin, though his large almond-shaped eyes still shine bright, tired and fiery.

Neel had a troubled life, suffering a mental breakdown and suicide attempt after her first daughter died and her second was taken away by her birth father. Aside from some early dark brooding paintings from around this time, her paintings of pregnant women, mothers and children are among her most emotionally disturbing. The De Vegh Twins (1975) are reminiscent of Diane Arbus's photograph of a similarly spooky pair of young girl twins, though these are painted in florid shades – raven-haired girls in bright red dresses before a purple cabinet, one sitting and one standing, both oddly adult in expression. Many of the babies and younger children that Neel painted, however, appear like mad, hungry, needy creatures – eyes rolling this way and that and genitals outlined in black or blue. Pregnant mothers appear fraught, depressed and strange. Motherhood looks a frightening, overwhelming prospect here. Neel's ability to render skin by laying colours next to one another is wonderful, however, and shines in this series of young mothers. Self-Portrait (1980) sees Neel turn her gaze on herself, aged 80, naked and droopy, brush and rag in hand. She is light and sprightly, however, surrounded by colour and perfectly composed.

To 17 September (020 7522 7888)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments