Bridget Riley: From Life, National Portrait Gallery, London

Faces of a young op artist

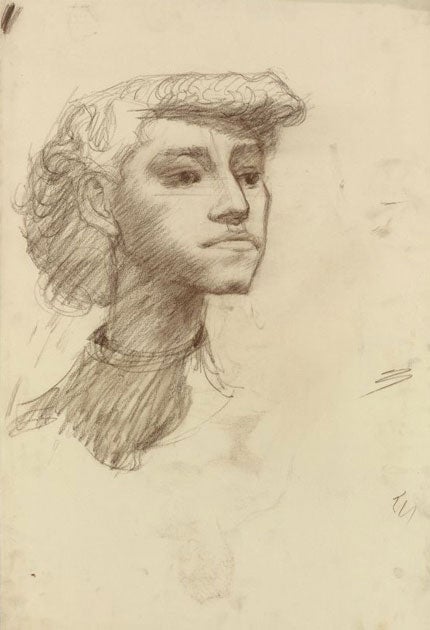

Bridget Riley is known for those intense paintings of colour and pattern that zip, swim and sing before your eyes. Flashing stripes, circles, triangles and ellipses that fool the eye into thinking that there are moving shapes on the canvas. Sometimes the strobing effect is so intense, you might have to look away. Often lumbered with the awkward mantle "op artist", this painter, now in her seventies, is one who has devoted her artistic life to understanding what might be termed "the eye's mind"; how form, colour and vision move us and excite us, and how the eye travels in an image. Such popular appeal did Riley's paintings have in the 1960s that copies of them made their way (much to the artist's chagrin) on to mini-dresses and curtains. While Riley's paintings of this kind are well known, just opened in a room in the National Portrait Gallery are some of her little-known sketches. The display comprises a few of Riley's portraits, drawn from life, made while she was a student at Goldsmiths college in the 1950s. On smudgy paper, worked and worried, sketchy faces of the artist's friends and family appear out of the page, often accompanied by a little cartoon or a preliminary sketch.

Riley has previously spoken about the way in which life drawing was at the root of her practice. In the same way that looking at a Titian or a Seurat taught her about the underlying structure of colour and the way that colour moves the eye, understanding the human figure taught her to see the forms underlying the image. She spent a lot of time in the drawing room in the British Museum, studying Rembrandt, Raphael and Ingres.

But what makes these portraits Riley's? The first thing is the sense of the bodies in space and their repose. Even though we only see glimmers of faces, Riley's rendering of these faces gives us a strong sense of where the rest of their body is, and how it lies. Louise Asleep is such a gentle image, shading on a woman's face and neck that, with light strokes, combines the restful softness of sleep in face and body. It's an entire composition yet we only see a glimpse.

The second thing you might recognise is a focus on the eyes and where her subjects are looking. Young Girl depicts a young, stubborn face, square jaw jutting and eyes looking, headstrong, into the distance. Older Woman Looking Down, however, is a sketch from the mid-1950s of a woman with a sharp face and sharp haircut. Both have begun to sag and her expression is soft. The depiction of ageing is somehow unbearably sad, because it is so mild, and the woman's downcast glance is elegant and resigned.

While these sketches offer an unexpected route into Riley's later work, it's hard to get her great paintings out of your mind. For those just getting to know Riley's work, I'd recommended looking at those paintings, the results of years of experiment and understanding, which surprise me nearly every time I see them. Her portrait drawings seen here are only the beginning.

To 5 December ( www.npg.org.uk )

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies