Charles Darwent on Chagall, Modern Master - The riddle of Marc's green donkey

He was in the right place at the right time – so why is Chagall regarded as an also-ran of Modernism?

Of the various words you might reach for to describe Chagall, "modern" is probably not one. Charming, whimsical, folkloric, yes; modern, no. It wasn't always like this, as the provocatively titled Chagall: Modern Master at Tate Liverpool sets out to remind us.

When Marc Chagall, lately Moishe Shagal, arrived in Paris from Vitebsk in what is now Belarus in 1911, he was driven there by the same need for modernity as Picasso had been a decade before. Studying in St Petersburg with the theatre designer Léon Bakst, he had caught wind of what was going on in France – Cubism and Fauvism, and the first rumblings of those other –isms that would together make up Modernism.

And so the Tate show opens with the 24-year-old Chagall like a kid in a toy shop, unable to choose which of the shiny new French styles to play with first. Back home, he had been taken with Gauguin. The Yellow Room, among Chagall's first Paris paintings, hints at the house in Arles which Gauguin had shared with Van Gogh, at Vincent's picture of his bedroom there. A few feet away, Nude in the Garden flirts with late Renoir, still very much alive and painting in 1911. Moving swiftly on, Nude with Comb tussles with Cubism, while Half-Past Three (The Poet) is an early sally into Orphism, invented only that year by the picture's subject, Guillaume Apollinaire.

Orphism, most famously practised by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, aimed to put colour back into the grey Cubist palette. In the ancient battle of disegno and colore, drawing and colour, Picasso and Braque had come down heavily on the side of the first. This did not suit Chagall, whose Russian eye was tuned to emotion.

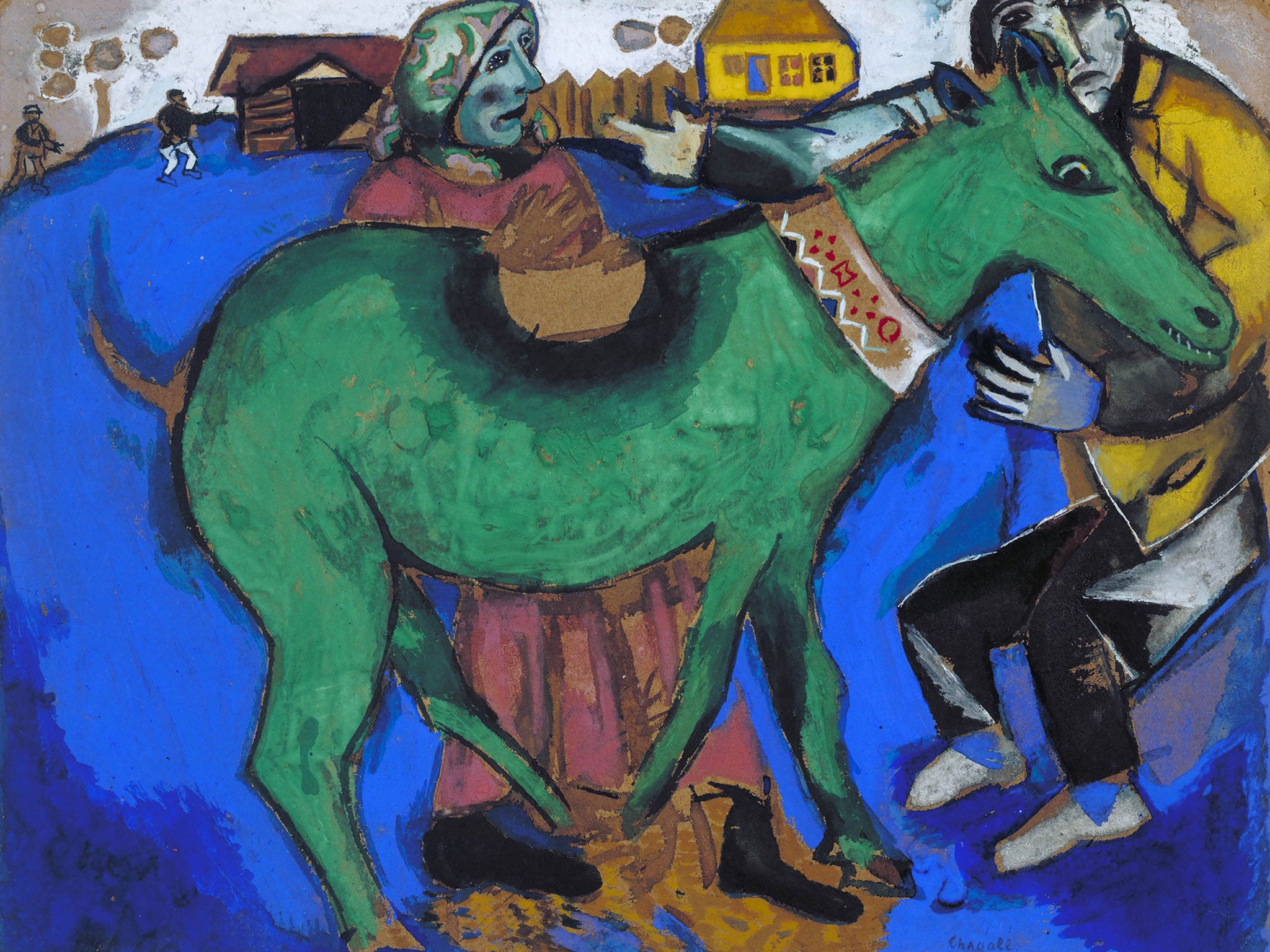

Thus The Green Donkey. Painted within months of his arrival in Paris, the work is curiously un-French. Perhaps Chagall had been reading On the Spiritual in Art, published that year by his fellow Russian, Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky had allocated specific psychic qualities to individual colours, even though the restfulness he ascribed to green hardly fits Chagall's nightmarish ass. The Green Donkey does resemble another one-colour quadruped, though, this being the one ridden by Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) on the cover to the manifesto of the movement of that name.

Co-founded by Kandinsky, Der Blaue Reiter's first show was also held in 1911, although not in Paris but in Munich. The movement would evolve, a decade later, into German Expressionism. And it was in Berlin as an Expressionist, rather than in Paris as an Orphist, that Chagall first found real fame.

Phew. My apologies for this canter through early 20th-century art history, but its speed is rather the point. What the Liverpool show wants to remind us is that Chagall was at the heart of modernism as it was being made, and that is certainly true. Within a year of coming to Paris, he had been a late Impressionist, a Post-Impressionist, a Fauvist, a Cubist, an Orphist and a proto-Expressionist. Even his archaisms were modern.

The couple wrestling with the green donkey form part of that universe of Russian-Jewish peasantry which now defines Chagall as a painter. Seen from a century later, this seems nostalgic – a yearning for the shtetls around Vitebsk and the woodblock prints of Yiddish fairytales on Chagall's part, for a world swept away by Stalin and Hitler on ours.

Babushkas in headscarves and pedlars with sidecurls do not instantly suggest modernity. And yet they were modern, part of that same yen for the primitive that linked Gauguin's Breton women to the African masks of Picasso.

So why doesn't Chagall feel modern, and why don't we think of him that way? Why, in short, does he need reappraising by Tate Liverpool? Next year, the gallery will host another of its series of monograph shows, of an artist who also left home in 1911 to look for the future in Paris: Piet Mondrian.

Mondrian certainly strikes us as modern. How come?

In part, the answer is in his work. To the victor go the spoils. Abstraction came to be synonymous with modernity, and Mondrian painted rectangles rather than flying cows and rabbis. But there is probably something more to it than that.

In 1911, Mondrian hit on the programme of painting that would occupy him until his death more than three decades later. His career was as linear as the grids he made; single-mindedness was a very modern quality.

Chagall worked in a way that now seems pre-modern – and even post-modern – but not modern. By the austere lights of Mondrian, he seems insincere, a painter of modishness rather than modernity. Perhaps he was. This show doesn't really ask the question, and it certainly doesn't answer it.

To 6 October

Critic's Choice

Do a double at Tate Britain: new exhibitions of Patrick Caulfield and Gary Hume have opened simultaneously and under a single ticket. It's a clever pairing, for while they are discrete shows, their proximity also reveals fascinating parallels in the painters' bold use of colour, flatness of imagery and cool distance from their subject (till 1 Sep).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies