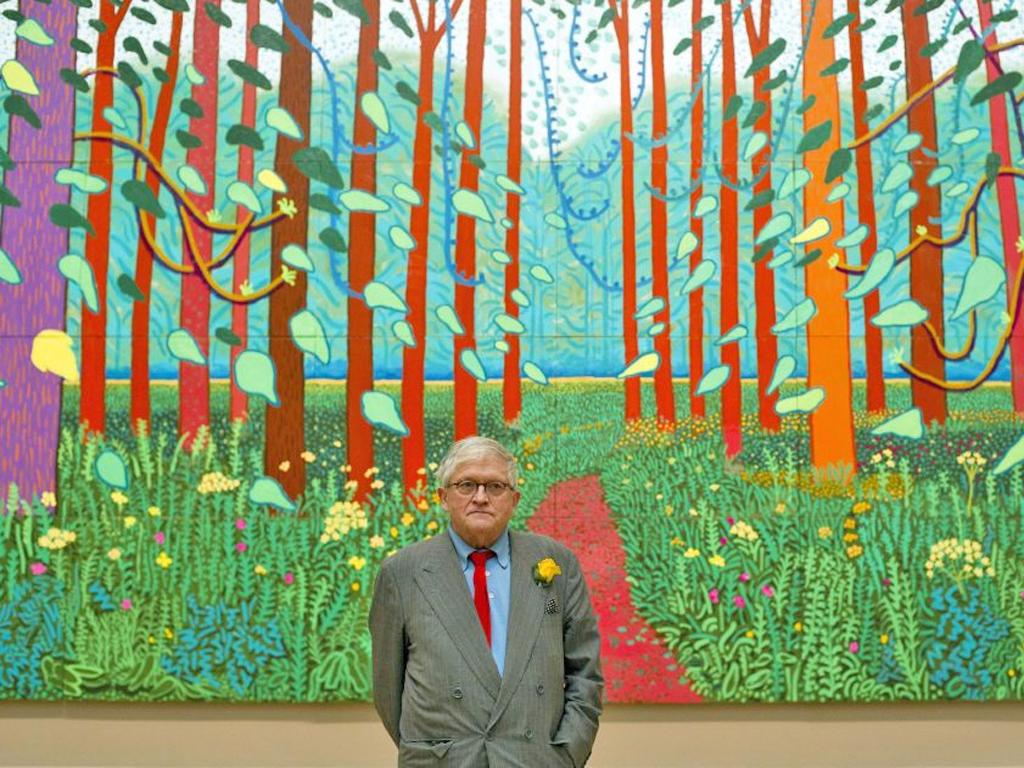

David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Someone should have stood up to Hockney over this uneven show full of wonders ... and horrors

Most weeks, choosing the armchair lady to put at the top of this column is easy enough, exhibitions being consistently good, bad or so-so. Not this week. No armchair lady exists who could encompass the horror of some works in David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture, and the wonder of others. Given that our designers might struggle to devise a figure throwing streamers with her left hand while putting a gun to her head with her right, I am going to award this schizophrenic show two armchair ladies, one standing and clapping, the other slumped in despair; the first time I've done so in 13 years as a critic for this paper.

The problem is one of power. As artists get older and more established – Hockney is 75 this year – so their position becomes less assailable. If England's greatest living painter wants to put 200 works in his Royal Academy retrospective, rather than, say, 50, who will tell him not to? This is especially problematic because Hockney's fame rests on his fecundity.

Once upon a time, there was Hockney, the painter of Speedos. Now, there is Hockney the set designer, Hockney the returned Yorkshireman, Hockney the iPad doodler, Hockney the film maker and a number of other Hockneys, each jostling to make their voices heard. The artist himself is clearly of the view that each of these voices is worth hearing. I am not.

Let's start with the good news. As you walk into this show, you find yourself outside the Wolds village of Thixendale. Hockney has painted a stand of three trees four times, in spring, summer, autumn and winter. Seeing this quartet in reproduction does not prepare you for the beauty of its parts. There are times when Hockney's mania for large-scale painting – note the title of this show – has seemed a bit of a con, when the size of his landscapes has allowed him to coast. Not with the Three Trees.

Each picture is roughly two metres high by five wide and is made up of eight canvases, two deep and four long. The joins between them impose a grid on the work's surface, suggestive of Modernism but also allowing us to take in a vista that would otherwise be too large to see. More than this, the gridded surface of the Three Trees pictures places a distance between us and the landscape, so that seeing becomes remembering, an act tinged with loss. The trees themselves have the Englishness of Constable or Rudolph Ackermann, a love of place made urgent by Hockney's having once misplaced it. And his talents as a colourist, as a painter of coded forms, come to the fore in this quartet. Up close, the ploughed field of Autumn dissolves into dots, some of them in a very un-Yorkshire shocking pink. And yet the feel is absolutely that of a field in autumn, a time of day.

A quick dip into the adjoining room of vintage Hockneys shows that this ability to evoke rather than replicate has always been his strong suit. In student works such as Fields, Eccleshill (1956), he paints in the fashion of the day. By his early twenties, though, Hockney has found his own way of encoding landscapes in shapes and colours that have nothing to do with reality but are entirely recognisable as real. No Yorkshire house has ever been the Jaffa-orange of the ones in The Road to York through Sledmere, and yet the colour resonates in the way that red brick does in the long-shadowed late afternoon. It is more than just prettiness. Hockney's look is decorative for sure, but then so was Matisse's.

So much for the standing, clapping lady; now for the slumped one. I do not know if Hockney used an iPad in making the works in the section called "Watercolours and first oils from observation", and I do not care. The pictures, a great many of them in a very large space, have the bleached look of a computer screen in an over-sunny room. They have none of the genius – not too strong a word – of Hockney's charcoal drawings of the winter timber that gives its name to a vast painting with a Symbolist palette.

I can see why Hockney would be fascinated by Claude Lorrain, who, like him, invented a light that was more real than real. But his computer-cleaned takes on Claude's Sermon on the Mount are just appalling: it is as well that the dead cannot sue.

The film wall is tacky, as well as misleading. It gives the impression that Hockney's multi-part canvases are just a bit of fun, which they are not. Had this show been better edited, we might have come away from it thinking of him as the pre-eminent painter of our day. As it is, I wonder if it will not damage his reputation. After those years in California, Hockney of all people should know that bigger does not always mean better.

Royal Academy of Arts, London W1 (020-7300 8000) to 9 Apr

Next Week

Charles Darwent moves on to Migrations at Tate Britain

Art Choice

The Italian Abstract Expressionist Alberto Burri proves a neglected master at London's Estorick Collection (to 7 Apr), while Graham Sutherland: An Unfinished World does much to rehabilitate the British Modernist at Modern Art Oxford (to 18 Mar). Or go dotty in London with Damien Hirst's spot paintings at the Gagosian Gallery (to 12 Feb).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments