Gabriel Orozco, Tate Modern, London

Matters of life and death

The atmosphere of Gabriel Orozco's exhibition at Tate Modern swings, quite brutally, between play and ponderousness, laughs and tears, lives and deaths. There are chess boards, lumps of plasticine and a billiard table in the show. However, like Ingmar Bergman's famous depiction of a chess match between a man and the grim reaper in The Seventh Seal, you might end up feeling as though you are playing for your life. You might be lucky, you might not.

One doesn't get far into the exhibition before we are staring into the empty eye sockets of a human skull. This couldn't be further from the diamond-encrusted one created by Damien Hirst. Orozco's skull, Black Kites (1997), is decorated in a chequerboard pattern in delicate grey graphite, and it was made after the artist came out of hospital, faced with his own mortality after suffering a collapsed lung. Surrounding this work is Orozco's Obit series (2007), large paper prints on which fragments of headlines, recognisably in The New York Times's font, float in a sea of white. Each is a descriptive element from an obituary, and it's affecting and frustrating to see a lifetime summed up in a single sentence: "ballerina with a comic touch", or "painter known on both coasts". The size of the font is relative to the deceased's public stature, so whilst "Reshaped US Art" looms large, "Student of dinosaurs" is tiny. Most of us won't even merit a line in 6pt when it's our turn to go.

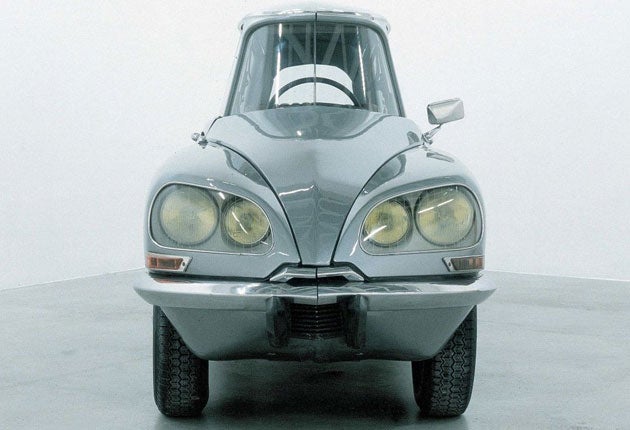

Before you become gloomy, however, there are light touches everywhere too. Three strips of lavatory paper hanging from the blades of a white ceiling fan create fragile, spinning ribbons. A chessboard is given entirely over to the knights in Horses Running Endlessly (1995), roaming free with their strange jumping move: two squares forward, one to the side. A Citroë* DS has been sliced, lengthways, into three, with the middle section removed, so that it is streamlined into a long single-seat vehicle. Its headlights and the front bumper give the impression of a pursed human expression. Though this is one of Orozco's best-known works, I find it not much more than a charming curiosity.

The most compelling elements in the exhibition are, for me, the works that explore what can be caught or contained within a sculpture or an image. An empty shoebox on the gallery floor; a photograph of a puddle with a reflection in it, upset by tyre tracks; a dog sleeping in a canopy created by a rock. Dial Tone (1992) looks like a long Japanese scroll, an ancient artefact, but is made from long columns of New York telephone numbers. The co-ordinates of families and businesses, now old data, are a memorial to an endlessly changing city. The final room looks as though it is hung with washing lines, on which are draped fragments of greyish delicate fabric. Lintels (2001) was made using the lint that collects around the filters of drying machines. Occasionally streaked with red and violet, they shiver as one walks beneath them, like dead husks that we leave behind and shrug off as we move though life. They mourn us, after we are gone, nonetheless.

To 25 April (020 7887 8888; www.tate.org.uk) Media partner, The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks