Hans-Peter Feldmann, Sepentine Gallery, London

A German artist who arranges found objects claims that he is merely an archivist, but the stuff doesn't just fall out this way

There is doubtless a word in German for the mood that pervades Hans-Peter Feldmann's work, something involving Schmerz, perhaps, or maybe Gestalt. It is a mood that is not restricted to Germans.

Tony Cragg, a very English sculptor, suffered from it at the start of his career, when he first moved to Wuppertal, near Feldmann's home town of Düsseldorf. Cragg would scour the banks of a neighbouring river for bits of like-coloured plastic – shards of blue bleach bottle, say – and turn them into two-dimensional sculptures. They were lovely, in a Povera kind of way. But they also seemed specifically local, to do with German history, a need to remake from fragments, to work in a childlike way.

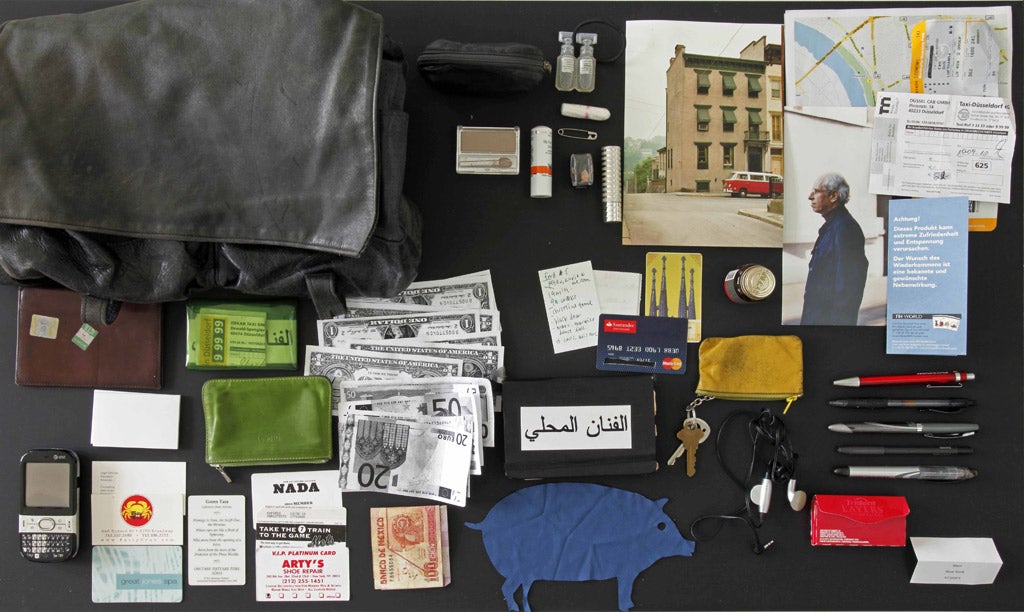

In Feldmann's case, this urge to reconstruct has taken a more conceptual turn. In his show at the Serpentine Gallery – the first, oddly, in a British public artspace – is a group of five vitrines, each containing a woman's handbag with its contents emptied out and put on display. These Feldmann bought from their owners intact: you wonder how he broached the subject.

One vitrine is labelled Susanne, Berlin, 38 years, its handbag a garish red number with a torn handle, the contents including Chanel nail varnish and face powder, a BlackBerry and a great many cigarette filters. By contrast, Renate, Cologne, 43 years has artistic interests – there are art postcards and gallery tickets – while Oriane, Berlin, 27 years (old Nokia, pebble, earplugs, L'eau d'Issey roll-on, scuffed shoes) seems the most scatterbrained.

Seen under glass, the handbags have the feel of evidence, perhaps from a mugging. What we deduce from them is the characters of their owners. Feldmann is big on the idea of completeness, of Vollständigkeit. Here are the total contents of a finite thing, unedited and unmediated. And yet for all their information, for all their intimacy and unguardedness, the vitrines remain entirely boring and unrevealing.

That, in a nutshell, is Feldmann's message, restated again and again in different media over the past 40-odd years: more knowledge is only ever more knowledge, never omniscience. When he photographs each of the 68 strawberries in a half-kilo box individually and tacks all the pictures to a wall unframed and unadorned, we can truthfully say that we have seen every strawberry in a particular punnet. And so what? It tells us nothing of the essence of strawberries, of strawberriness. Likewise with the six beautifully printed and framed slices of rye bread on one wall of the Serpentine's central gallery, or with the sequence of shots – empty frame, bow, whole boat, stern, empty frame – of a tug passing up the Rhine.

It is, in its strange way, compelling: the more evidence Feldmann gives us, the less we know; the stronger his positives, the more we feel the negatives around them. In a curtained-off niche in the Serpentine's West Gallery is an installation called – unusually for Feldmann, who prefers his work anonymous – Shadow Play. This consists of a trestle table with spotlights on it made from coffee tins, each light illuminating a spinning turntable covered in what can only be called "stuff": from memory, a statuette of the Eiffel Tower, another of HM The Queen, a model of a British Airways jet, the upper half of a Barbie, two bridal couples (one heterosexual and one same-sex) from the tops of wedding cakes, and much, much else besides.

You could go on reciting the ingredients of Feldmann's recipe until you were blue in the face, although no amount of listing would prepare you for the outcome. Projected on the niche's back wall, à la Noble and Webster, is the shadow play of the work's title, a joyous and yet macabre place, redolent of fairgrounds and travel and glamour but also of Hitchcock and nightmares. As with Webster and Noble, the trick is not in the transformation from solid to shadow but in the fact that we are still amazed by it even though we can see – we are forced to see – how it is done. Facts, in Feldmann's world, are not an antidote to astonishment, nor to ignorance.

All this makes his insistence, often voiced, that he is not an artist faintly irritating. For Feldmann to say that he is merely an archivist is less modest than it sounds. Beneath this claim is the suggestion that his work is unmediated, honest, found rather than made. That is not childlike: it is untrue. The contents of Renate's handbag have been laid out differently from those of Susanne's, and it is Feldmann who did the laying; likewise, who chose when to press the button of his camera as he stood by the Rhine? Or what junk to put on Shadow Play's turntables? But his belief, in the end, is that we should never believe anything – including him.

To 5 June (020-7402 6075)

Visual choice

Gillian Wearing gets a first retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, east London. See if you can stare down her personal, pithy photographic works and films (till 17 Jun). Industrial steel sculpture in the grounds of a stately home? That's the unlikely juxtaposition at Chatsworth House in Derby-shire, where 15 of Anthony Caro's works have found a home till 1 Jul.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks