Pop life: Art in a Material World, Tate Modern, London

In a Warholian world where more is more, Jeff Koons has plenty to brag about ... or has he?

The sharp-eyed among you will note that we never see Jeff Koons's face and penis at the same time in his Made in Heaven series; that, while both ends of Mrs Koons's anatomy co-star in works such as Glass Dildo, – "seminal" is, I think, the word – her husband's head and his, apparently heroic, member always put in separate appearances.

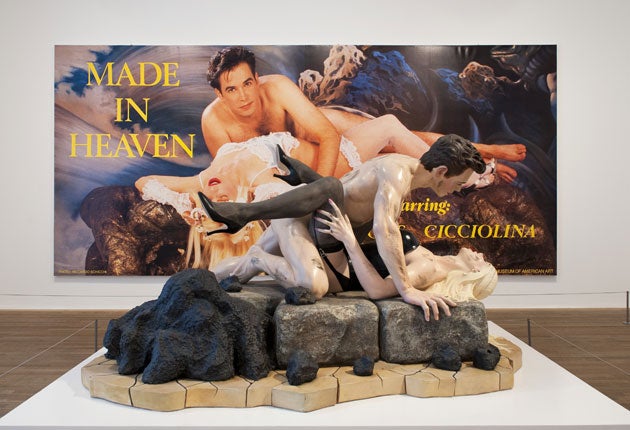

The only work in which the two organs are shown together (although much of the latter is inside Mrs Koons at the time) is in a large plastic sculpture called Dirty – Jeff on Top. Since this piece also depicts the, in truth rather weedy, artist as a muscleman, it can hardly be admitted as evidence. Which prompts the question: has Koons been stunt-dicked, as they say in porn circles?

If this sounds a minor issue, it is variously at the heart of Tate Modern's new show, Pop Life. Since the Sixties, honesty has become synonymous with sexual candour. True portraiture must show not just warts but all other protuberances as well. More is more, a creed we owe to that high priest of excess, Andy Warhol.

It is Warhol who starts Pop Life, and who hogs its first four rooms. Towards the end of his career, Andy is widely held to have taken Andy-ness too far. It is one thing to run off silkscreens in a studio called The Factory, quite another when those silkscreens – portraits of Hockney and Jagger and the putty-skinned denizens of Studio 54 – become so cynically alike as to be million-dollar snapshots. Critics who carp at Warhol for this, who compare his decadent late phase with a supposedly purer earlier one, are missing the point.

The Warhol project was always about reducing the making of art to a level of mass production or, perhaps, elevating mass production to the status of art. You can not chastise the Virgil of banality for being banal.

In token of this, Warhol turned himself into a brand, a self-advertisement for self-advertising. In Room 1, he appears in a Japanese TV advert for TDK video cassettes, zombily mouthing Japanese pho-nemes, a-ka-ni-dori ao-gunja-ero ki-bei. In Room 4, we see him in an episode of the cheesy Eighties series, Love Boat; next door, Andy tells jokes on Saturday Night Live. ("D'you know where Prince Charles spent his honeymoon? Indiana".) It is all, quite intentionally, dreadful.

It is also moral, an understanding at the centre of this clever, subtle show. By suspending critical judgement in his own art, Warhol also suspended moral judgement. Questions of better-than and worse-than (and, indeed, different-from) simply don't apply, a relativism that spills over into the world Warhol's work portrays. If art itself is no better than tinned soup, then how can it be a repository of truth? Warhol, a great moralist, taught us one thing, and that was not to trust our eyes. (The furore over Richard Prince's shot of a nude, pre-pubescent Brooke Shields, recently removed from this exhibition, suggests he may have had a point.)

And so with Koons, whose Made in Heaven suite is self-advertising at its most primitive, a man lying about the size of his willy. If the leap from Warhol to Koons isn't much of a stretch, jumping from Warhol to Damien Hirst calls for ingenuity. Pop Life cleverly repositions Hirst in the history of art, lending him a masterliness I'll admit to having never seen.

Hirst is by no means a Pop artist, but he is a Warholian. By this I mean he is a moralist, a man concerned with the value of value. Why and how is art different from soup? asked Warhol. Hirst's variant on the theme is: How is it different from bling?

Warhol's 1979 Gem paintings of diamonds are made of diamond dust and shown under UV light. They speak with the accents of the late Liberace: "Wanna see my rings? You paid for 'em." Hirst's diptych-vitrine of diamonds, Memories of/Moments with You (2008), is equally mocking, but in a different way. Where the Gem works are intentionally slipshod, Hirst's is engineered to microscopic tolerances (not by him, of course). At the work's heart, as with Hirst's diamond-encrusted skull, are questions about how we value what we value, about capitalism's dark materials. Pop Life traces this anxiety in modern art cleverly and compellingly, and my only kvetch, as with many Tate Modern shows, is that it is too big. Linking Warhol, Koons, Hirst and Murakami would have been brilliant; throwing in all the others – Cosey Fanni Tutti, Andrea Fraser and the rest – is too much. Just because Warhol thought more was more doesn't mean it's true.

Tate Modern, London SE1 (020-7887 8888) to 13 Dec

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies