Red Star Over Russia, Tate Modern, London, review: The walls are a furious flurry of visual stimulation

A visual history of Russia and the Soviet Union from 1905 to the death of Stalin includes rare propaganda posters, prints and photographs, mainly from the collection of David King

Intimate conversations are woven into the very fabric of Tate Modern, don’t you find? This morning a senior staffer and I were roughly at mid-point in a new exhibition about the history of the visual culture of the Soviet Union, when a rather personal question emerged: what was your first love? Various faces swum into view, only to fade again. Then one of us blurted it out, as if on cue: the Russian Revolution! We then went on to talk, somewhat dispiritingly, about the present-day difficulties of trying to off-load multi-volume, English-language editions of the collected works of Marx, Engels and Trotsky to unsympathetic, right-leaning second-hand book dealers. Blackguards all.

This exhibition, then, is exactly for the likes of we old-guard pinkish nostalgists. And perhaps it is for the likes of you too. It consists of a mountain of visual stuff amassed over decades by a designer called David King who, in addition to his passion for collecting the visual memorabilia of the Soviet Union – postcards, photographs, posters, books, letters, etc – also had a wish to forge a new visual style for the Left. Did he succeed? Goodness knows.

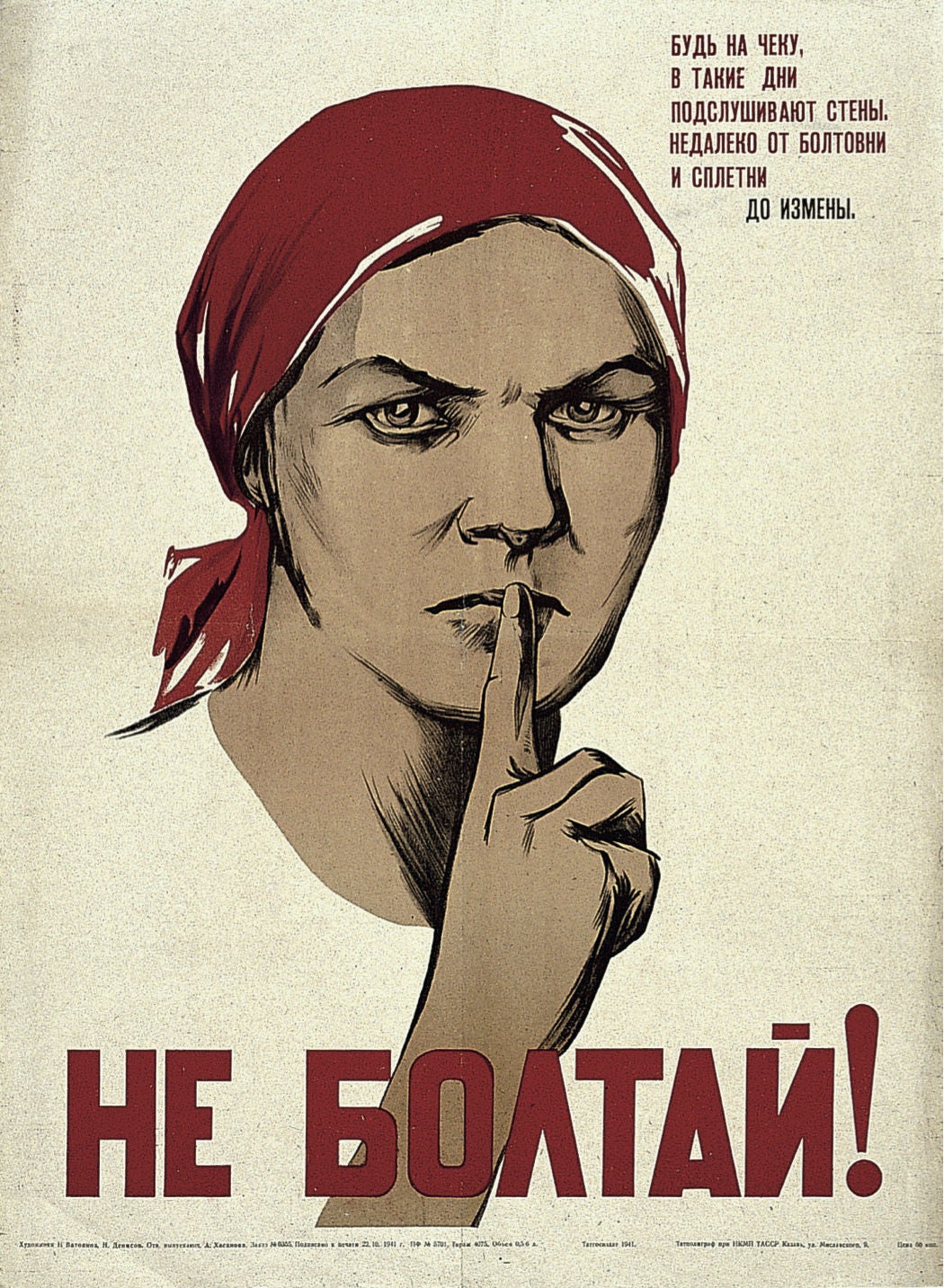

This exhibition is the story of how the Soviets strove to create a new visual identity in the service of the revolution, and it contains many, many objects, mainly small to medium in size. The walls are a furious flurry of visual stimulation. There are very striking posters, run-of-the-mill posters, and much in-between. There is much fist-shaking, much hollering, much sloganeering – ”Send Your Son to the Red Army, the Best and Foremost” – and much thrusting forward of red bayonets in the general direction of a roseate future. There is also interesting photographic evidence of useful, humdrum work undertaken by the many on behalf of the revolutionary ideal: the making of banners, for example.

Many of the best works here are by a handful of excellent artists and designers such as El Lissitzky and Rodchenko, who put their talents to the service of what they hoped would become a transformative collective endeavour, issuing in the birth of a new kind of creature altogether: Soviet Man (and Soviet Woman). Unfortunately, human nastiness crept in – bloody rivalries, brutal and brutish enforcement, pogroms, enforced collectivisation. It all ended in tears. Idealists such as Mayakovsky were driven to suicide. Trotsky was air-brushed out of the picture, then, years later, assassinated in Mexico. We can watch a splicing together of archival film which shows how he first strides the stage as a cultural commissar. By 1927, he had disappeared from the official record altogether. Enforced forgetfulness. There was much of that.

The largest single object is in fourth room, where the eye-catching Soviet Pavilion of 1937, raised at the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Paris, is remembered. We see an image of the pavilion soaring up skyward, part modernist, part socialist-realist, beside the Seine in a grainy photograph, topped by a steel sculpture of two workers who walk side by side, arms raised, one carrying a sickle, the other a hammer. The all-records-breaking Stakhanovite worker-families in a painting by Aleksandr Deneika look as emotionally unconvincing as they are dull and wooden in execution. Fabricating the truth comes at a price.

‘Red Star Over Russia: a revolution in visual culture’, Tate Modern, until 18 February 2018 (tate.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments