How crowdfunding is enabling indie talent to create graphic novels

The graphic novels industry has always been damnably hard to break into – but crowdfunding, says James Moore, is changing that for indie talent

It starts with a booze-soaked, cross-dressing grifter reaching the end of the road in a stolen car before flashing back to tell the story of how she got to that unhappy place: leading a burlesque troupe in their attempt to avenge a co-worker’s murder by gangsters in prohibition era San Francisco.

Marvel and DC have their fair share of mature titles but would even one of their adult imprints publish something like The Tommy Gun Dolls?

Creator Dan Cooney wasn’t interested in finding out, turning instead to a form of financing behind an increasing number of indie writers and illustrators, who are either unable to crack the big publishers, or who just want to hold on to the rights to their own work.

He crowdfunded his beautifully produced 94-page graphic novel via a Kickstarter campaign.

I meet Cooney at his stand in London Comic Con’s Comics Village, which, according to organiser MCM, has seen a 15 per cent increase in the number of independent artists like him displaying their work since the October 2017 event.

They have produced a wildly diverse bunch of comic books and graphic novels. As well as Cooney’s 1920s noir, you can find work in the genres of fantasy, sci-fi, history, modern crime. Not forgetting numerous sideways takes on the superhero genre. Some feature multiple genres. Some create genres of their own.

Cooney has flown over from Massachusetts, US, where he lives and works, to show off his wares and tickle the fancy of potential customers.

He dreamed of writing and illustrating comics as a child, as many do. But the industry is a bit like journalism in that there are a lot of people wanting to get into it despite it being damnably hard to do so unless they have connections, or get very lucky.

“To get the attention of publishers, you have to submit a tonne of work on spec,” Cooney explains. “You don’t receive any monetary compensation for submitting pages to publishers.”

He had a stroke of luck while in college: he got the opportunity to intern at Marvel while in his final semester at the School of Visual Arts in New York in 1998.

“I saw firsthand how the whole process worked from the business end of compiling a comic book,” he says. “The thing is, as much as I loved the characters of Marvel and DC Comics that hooked me as a kid into reading their adventures, I had a stronger desire to write and draw my own stories. I wanted to own the stories I published.”

This isn’t uncommon. If a creator signs up to produce characters for a corporation they have to put up with what that corporation may decide to do with them after they’ve finished. It doesn’t always work out how they would like, as the tumultuous relationship between legendary creator Alan Moore and DC over his Watchmen graphic novel shows. To his great displeasure, DC published prequels, and is now in the midst of a sequel, all written by other writers.

Moore famously refused to take royalties from the film version.

Going it alone, however, can be costly. For 18 years, the cost of printing work and shipping it to distributors, (which would inevitably take a hefty cut), came out of Cooney’s pocket, often with the assistance of his credit card. Getting a return on his investment wasn’t always easy.

“The distributor in the US takes about 64 per cent of your retail cost to deliver your book into the hands of comic book retailers, speciality shops and bookstores,” he says.

With independent publishers getting squeezed, life was getting particularly hard for those not able to hit certain benchmarks.

“If your orders were low with the distributor and the titles were dropped, it made it even more difficult to move inventory,” he explains. “All you had were comic book conventions and local comic book shops supporting your work.”

Then Kickstarter came along, eliminating many of the problems he identified. To Cooney, the attractions were obvious, all the more so given the changes the industry was going through when he first took the plunge.

“It takes a small percentage of the total earnings raised during your campaign before disbursement of funds into your business account,” he says. “These are used to cover printing costs, rewards, packaging materials and shipping.

“There’s a subculture of a supportive comics community of creators and readers helping one another – that alone was enticing enough for me to give it a shot.”

He was not alone in that. Kickstarter says that between 2012 and 2017, the number of comics and graphic novels successfully funded via on the platform grew by 135 per cent – from 542 in 2012 to 1,283 in 2017.

The amount pledged over that period grew by 40 per cent – from $9.1m (£6.m) to $12.7m.

Jon Leland, senior director of strategy and insights, says this indicated “a particular increase in small and moderate indie comic projects funding on the site after some larger creators in the community established the viability of the model early on”.

He also says that success rate has climbed, from 47 per cent to 64 per cent. Comics projects with at least 25 backers boast an 80 per cent hit rate.

If there is a downside it is that it offers an all or nothing deal. With Kickstarter, you either get everything you want or you get none of it.

“All-or-nothing funding is a core part of Kickstarter,” says Leland. “It’s less risky for everyone – if a project doesn’t reach its funding goal, creators will not be expected to complete their project without the funds necessary to do so, and backers will not be charged.

“It motivates – adding a sense of urgency motivates your community to spread the word and rally behind your project.”

But you do need the community: “If you don’t personally know 25 people who will want to support your project on day one, you probably aren’t in a position to launch a campaign.”

Corey Brotherson is one who is more wary of the crowdfunding route. I meet him alongside his sometime collaborator Yomi Ayeni, with whom he has worked on the Clockwork Watch series of steampunk graphic novels, set in a London where Victorian values are married to an anachronistic technology, including huge floating Zeppelin airships and mechanical slaves.

With there being no set route into fiction writing, Brotherson, like many before him, initially turned to journalism for a career, specifically games journalism. This opened doors.

“I was introduced to someone high up at DC Comics via snail mail, and I also started developing a pitch to send to Marvel, around 2003,” he says.

“Neither one of those came to anything, through a combination of bad timing and ill-preparedness. The DC Comics contact left the company by the time I had anything ready to show, while the Marvel open submissions closed within days of me finishing my Silver Surfer and Sleepwalker pitches.”

Lesson learned, he set his sights on making sure he had stories to write that he could go about getting published. His very first was hosted by an anthology, soon after, he became a semi-regular for the series and was getting picked up for work-for-hire jobs and small press call-outs.

“I’ve not looked back since,” he says. “I’ve had conversations with some of the bigger publishers in the medium in the last few years, but nothing has come of them as of yet.”

Brotherson was more wary of the crowdfund route having been involved through working with Ayeni.

He explains: “I’ve always been curious about crowdfunding, but was nervous about the logistics, setting aside the time to do a good job when that time could be spent on the actual comic itself.”

He worried about the the wait faced by people who pledge: those who join crowdfunds usually receive rewards for their participation, but projects can take time to come to fruition.

“These things almost always take longer than planned,” he says. “If you have something nearly complete and you’re still asking for money for it, will prospective funders not just feel it’ll be made anyway without their cash? In the end, one or more of these factors usually put me off.”

Brotherson says being part of Clockwork Watch, which used Indiegogo, another crowdfunding platform, cemented those concerns.

“The project was a massive success and even ended up being singled out by Indiegogo as one of its top campaigns of 2012,” he says. “It gained a tonne of traction, a fair bit of press due to the interactive nature of the storytelling, and put our names out there.

“But it was a massive emotional burn. The project went close to the wire in terms of reaching its goal in time. Even though Indiegogo lets you ‘keep’ what you’ve raised, there are a lot of additional fees that need to be taken into account for your final raised amount, on top of things like perk costs, postage and packaging and printing – this is before you consider staff being paid.

“Yomi was stressed and constantly working on publicity to push us closer to our target, while work on the book continued and took up more time, and on top of that he was trying to get the pieces moving for the massive event that would launch the book.

“Any one of these things is difficult, but a crowdfunding campaign is exactly that – something that needs constant supervision, promotion and enthusiasm, even through everything else you’re doing. It’s all very exciting at the start, but eventually, you’re tired and almost sick from promoting it, as are audiences from overexposure. You need to keep pushing as it means you could reach that handful who could push you over the target.”

So it’s a marathon, not a sprint, and marathons have a habit of leaving those who compete exhausted.

Cooney also admits that crowdfunds can be tough. He says he felt like he had just completed a theses for an MFA (Master of Fine Arts) during the preparations for his successful Tommy Gun Dolls campaign. Even so, he’s leaning towards diving in a second, and perhaps a third, time: to complete the story of his Tommy Gun Dolls he needs to publish two more books.

“The whole process is stressful, particularly when it goes live,” he admits. “There’s always a part of me that has doubts that people will embrace my work. It’s the same reservations I had back when I decided to create samples on spec to break into comics.”

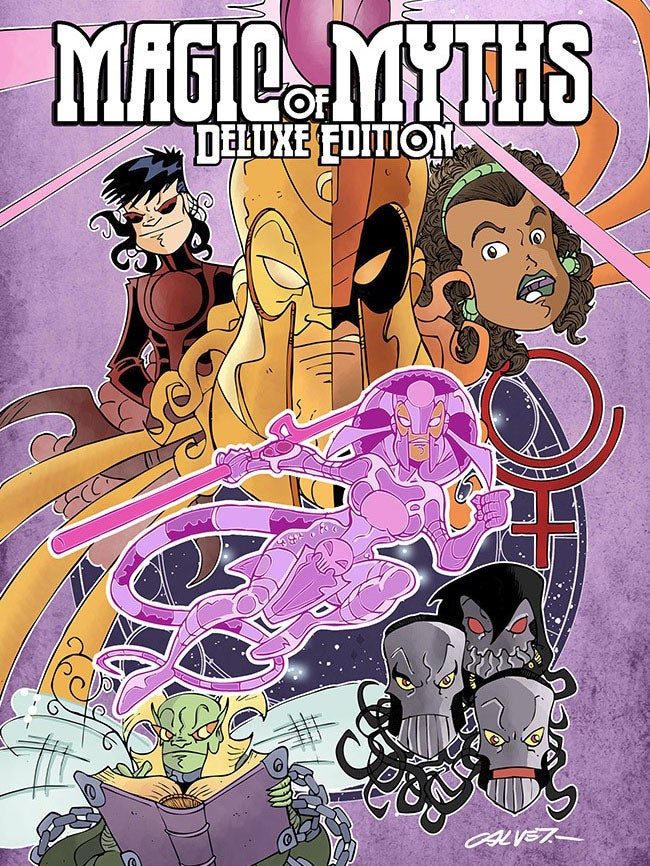

Nonetheless, he says he was convinced of the worth of it. Brotherson, however, is likely to continue using his own resources to get books, such as his Magic of Myths, the story of a teacher transported to a magical realm where she is caught up in a war between the Greek and Roman Gods, into print.

“Having seen what Yomi went through, and being a sounding board for another friends’ campaigns, I doubt I’ll go down the crowdfunding route any time soon for my own books,” he says. “My work has been part of three successful crowdfunded campaigns now, and I do feel the itch every once in a while, especially as it would be nice to not worry about funding entire series out of my own pocket, but then I remember the negatives that come with it.

“It’s easy to see the success stories and think you want a piece of that pie, but the work that comes with it adds to what is already a tiring and stressful endeavour. I work in the games industry full-time and it’s strewn with the corpses of failed campaigns for games that looked amazing.”

Regardless of the method of funding, the indie sector seems in vibrant health, at least if the village is anything to go by.

MCM Comic Con’s event manager Josh Denham says the space allotted to the village has grown by 20 per cent and “we are committed to growing this area of our show to give this talent the exposure they deserve”.

“One of the aims of the team is to provide a space for people to celebrate and work with independent markets, including creators, online influencers, indie artists, independent comic authors, etc,” he adds. “We make it a priority to offer an environment where these individuals and companies can elevate their presence and grow their business in.”

The pop culture world might be dominated by big budget superhero movies and TV shows, but he says audience feedback shows the desire for something different is strong. As such, there has been an effort made to feature independent creators and companies in the panel sessions, which are a highlight of the event for many of those that attend.

“We have noted that more and more visitors are on the lookout for less mainstream comic artists and authors as they are interested in exclusive artwork they can’t find anywhere else,” Denham says. “Without the presence of independent business and talent at our event, we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

Whether funded by the crowd or just by credit card, that’s good news for those who value the creativity and innovation that goes on outside the confines of the industry’s giants.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks