Human metamorphosis

In her new book, reflecting on how and why we change, Polly Morland explores 19 true stories. In this extract, she hears how a violinist who felt cut off from ‘real life’ took a 10-year journey to join the police

Overlooking a quiet street of suburban houses, with neat front lawns and heathery hillside beyond, Police Sergeant Coxon sits in a tidy, plain living-room. He is not in uniform today, but his bearing is straight and a little formal, almost as though he were. On the floor there are two large baskets overflowing with soft toys, plastic trucks and those fabric picture books designed to withstand chewing by their readership. Over the hours that follow, these baskets periodically emit an incongruous coda of melody, a bleat or a moo, a tinny siren.

Sergeant Coxon has just come off night shift and his baby son is teething. He apologises for being ‘‘a bit exhausted’’ and smiles, making a little circle on the closed lids of both eyes with surprisingly delicate, tapering fingertips. Recently promoted to sergeant after a decade as a front-line constable, Coxon’s beat is the southern hub of the Edinburgh urban area. There he and another sergeant run one of five emergency response teams, serving 120,000 people, from both affluent and deprived communities. His conversation is punctuated with glimpses of what he calls the ‘‘gritty’’ side of his work. Suicides, murder, sweeping brain matter off the tarmac after car crashes, the knock on an unsuspecting door with terrible news.

‘‘Appalling things happen to people on a daily basis,’’ he says, the decorous precision of his Edinburgh accent taming the chaos for a moment, ‘‘but you learn to deal with it and it’s made me a better person, being a police officer. My mind has been broadened immeasurably, my insight into what really goes on out in the world.’’ He glances to the street outside, where a man is whistling as he washes his car. ‘‘It’s actually given me great faith in human nature and it’s essential work.’’

Everyone is changed in some way, small or large, by the job they do, the particular window on the world it affords, but that is only in part what Edmund Coxon’s story is about. For insofar as any of us is meant to be one thing or the other, Ed, as people call him, was not meant to be a police officer. Indeed, the journey that brought him here to his black uniform and highly polished shoes is an immaculate example of why so many of us want to change: that confluence of organic, natural change process – call it growing up, if you will – with the sharp kick of individual agency that underpins all deliberate acts of transformation. It is a tale of how the reasons why we want to change, myriad as they are, all stem from a desire to be the author of our own lives and of how that can sometimes lead us to take on the most unexpected new forms.

On the subject of growing up, biologists have long argued that what happens to us during the transition from juvenility into adulthood is a change of body and mind more profound than any other we experience. A few have even maintained that the hormonally controlled differentiation that takes the human animal through adolescence could reasonably be considered a variation of the biological ‘‘miracle’’ of metamorphosis. It is a hypothesis that strikes an intuitive chord: we all know that the process of growing up, even well beyond our teens, changes who we are at some level. Indeed achieving our adult selves, learning to take control of our lives, often entails something akin to a metamorphosis, a profound transformation of our mode of being in the world.

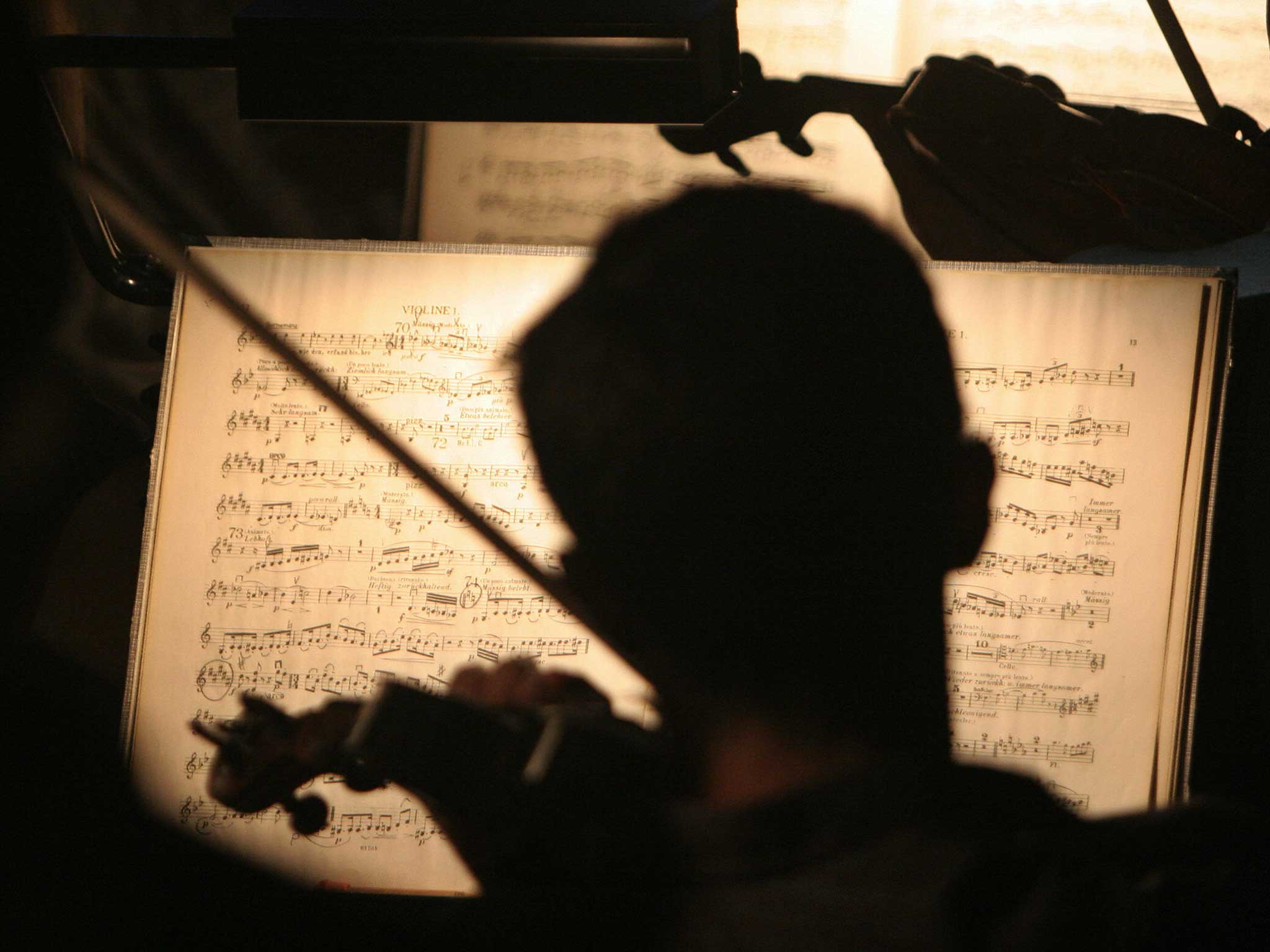

The only visible trace today of Ed’s big change, his metamorphosis, is propped up in a far corner of his dining-room – the cocoon of a black violin case. The instrument inside, as Ed mentions with pride, once belonged to the legendary violinist and conductor Sir Neville Marriner, founder of the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. For, strange to tell, before Ed Coxon became a police constable, he was a classical violinist with a career that saw him play in some of the finest orchestras in the world. Moreover, it was a life carved out for him and by him from his earliest childhood. A violinist was what Ed Coxon was always meant to be.

The son of a university classics professor and a singing teacher, Ed grew up in a house where music dominated. His little bedroom was next door to the room where his mother taught, with its grand piano, shelves of scores and gramophone records of operas, symphonies, quartets.

‘‘I was just enveloped in music," he says. ‘’It was’’ – he thinks for a moment – ‘‘a pre-existing condition. It never occurred to me I would do anything other than be a musician.’’ A chorister from the age of six in a specialist music school, Ed took up the violin at nine and had an immediate, dazzling aptitude for it. ‘‘Even when I didn’t have the instrument in my hands, I would play tunes on my fingers. I just had music going on in my head all the time.’’

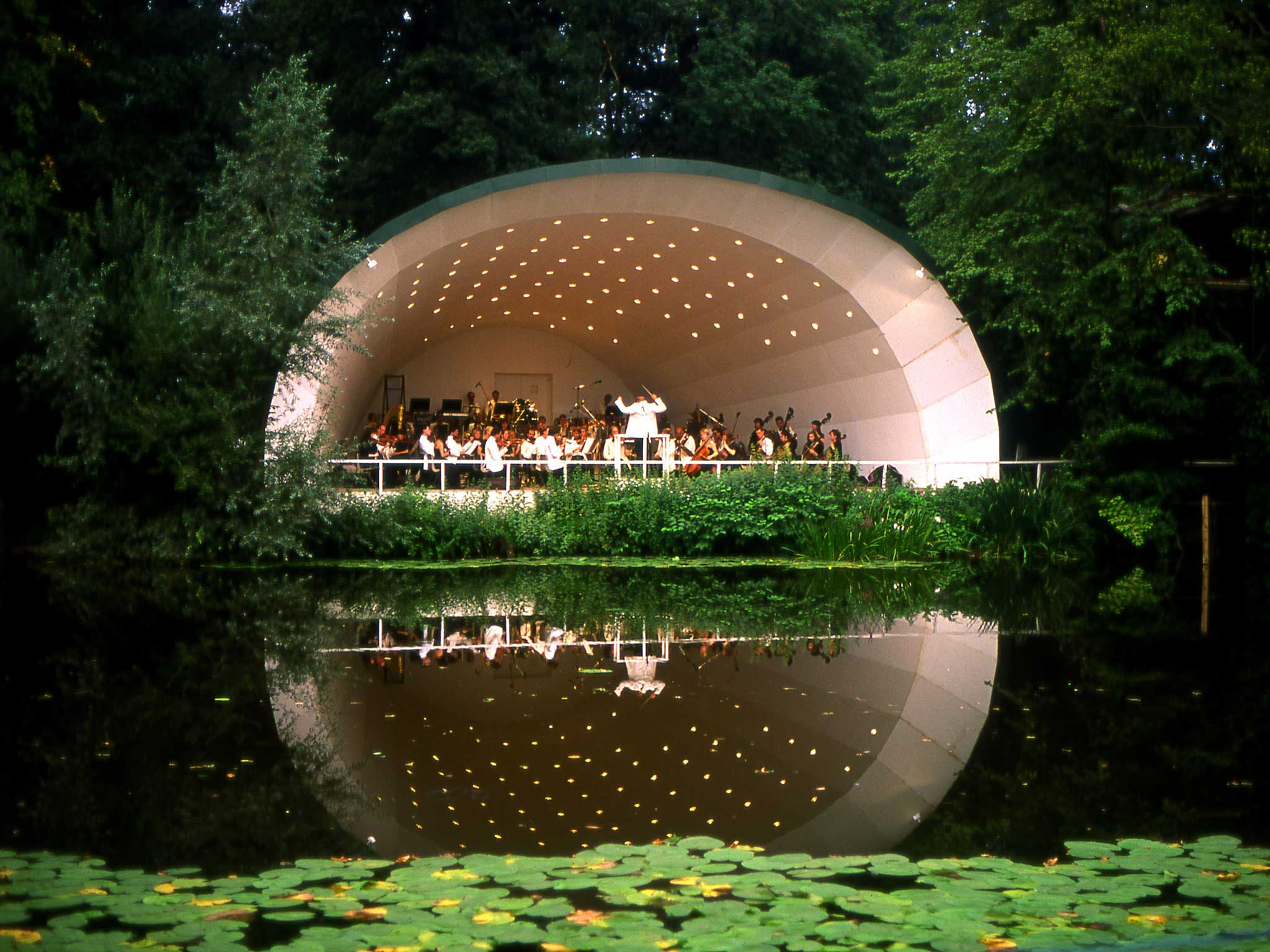

He describes with almost religious reverence going to a concert a few years later by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in the vast domed bulk of the Usher Hall, just below Edinburgh Castle. Looking down from his seat high above, Ed had thought, he now recollects with teenage intensity, ‘‘God, I want to do that. I’ve got to play in that orchestra. That is all I want to do.’’

The ease with which the police sergeant switches from talking about murder and car smashes to re-inhabiting the musical passions of his youthful self seems to show how unconditional that love once was. Yet it would be the tough realities of the real, grown-up world, both in and outside the music profession, which would begin to erode the young violinist’s idealism and his vocation.

At just 17, Ed went to music college in London and sure enough, by the age of 20 he was playing with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, whom he had heard in Edinburgh that decisive day. A promising career now unfolded. He toured the concert halls of the world, played for legendary conductors. Ed names them still with hushed reverence – Abbado, Bernstein, Dorati – like so many holy men. Meanwhile, he was growing up in other ways too. He offers a photograph of himself from the late 1980s, a moodily handsome young man dressed in concert black, his violin propped on one wrist, the very image of talent and confidence. ‘‘The only crises I suffered in those days were with girls’’ and Ed laughs a little mirthlessly. Without offering much more in the way of detail – his wife is in the room next door – he mentions that at 22 his girlfriend at the time fell pregnant. The couple hastily married and the baby was born.

‘‘I was too young, really’’, he says with a barely perceptible shake of his head. ‘‘And this was the point at which I realised life wasn’t quite so rosy, because I now was going to have to do things for other people’’ – he taps his knee with a fingertip as though bringing himself to account – ‘‘a child, a wife, bills, taxation. I’ve got to get through these auditions, because I’m responsible for this. I’ve got bills to pay.’’

On cue, a toy buried in one of the baskets pipes up with a few bars of "Pop Goes the Weasel" and, giving it a little kick, Ed explains that this is when the doubt began. ‘‘Well, maybe it wasn’t a doubt so much as a desire’’, he says. ‘‘I didn’t doubt that I wanted to continue in music, but I had the first seeds of desire to learn other things in life and that these were things that I possibly had a duty to understand.’’

The marriage lasted just 18 months, but the subtle shift of outlook that had accompanied Ed’s transition to fatherhood refused to go away. Instead, the questioning spiralled.

‘‘I felt like there was this disconnect between me and the outside world,’’ he says, ‘‘inhabiting, as I had for many years, this wonderful parallel universe of music and now I wanted rid of that insularity and to actually have a look, see what’s going on out in the real world. Because how connected to the real world is all this?’’ Ed holds an imaginary violin in the air for a moment, which then evaporates in his hands as he shrugs and says, ‘‘I began to feel that it’s not.’’

So one day, unbeknownst to his colleagues in the orchestra, Ed sat down in his Brixton lodgings and wrote the opening words of a new story for himself. Inked into blank boxes, the words filled an application form to become a Special Constable with the Metropolitan Police, the Constabulary’s part-time, unpaid volunteer force. And here came Revelation Number One: a reply came by return, inviting Ed for an interview.

‘‘It’d just been a kind of experiment, like dipping my elbow into the bathwater, you know? But now I thought, oh my God.’’ Ed beams for the first time all morning. ‘‘Somebody has an interest in what I can offer. And that was the first chink of light where I thought I can be something other than a musician.’’

All the same, Ed declined. He smiles, holding aloft two pale hands. ‘‘I thought, No, I can’t. It’s too dangerous. What if I hurt my fingers?’’ And off he went to rehearsal.

Anyone vexed by questions of why we want to change – what is reason enough? – and how on earth to begin, would do well to picture Edmund Coxon walking through the drizzle on the Brixton Road that day, violin in hand. On paper, nothing was any different. Yet the chorus of desires within him, all its complex internal counterpoint – that ‘‘why’’ of change – is where transformation itself quietly stirs into life.

This is the point at which I started to think much more seriously: what else is there? Because I just didn’t want to become that embittered person and there was every chance I might

An eminent mid-century psychiatrist, Alfred Benjamin, makes the point with an anecdote from his own life. Walking home from his Boston consulting rooms one evening, Dr Benjamin was approached by a stranger who asked him directions to a particular street. Benjamin cordially obliged, with a series of detailed lefts and rights that would lead the stranger, without delay, to where he wanted to go. The man paid close attention, nodding and confirming the specifics – ‘‘Left , you say? And then right?’’ – before thanking the kind doctor and bidding him good night. Walking away with a new purpose in his step, he set off up the street instead of, as Benjamin had carefully outlined, down it.

‘‘You’re heading in the wrong direction’’, the doctor called out.

‘‘Yes, I know,’’ replied the man over his shoulder, ‘‘but I’m not quite ready yet.’’ And back he went the way he had come.

There is little academic consensus on a grand narrative of why we change or how, but on one thing all psychologists and philosophers seem to agree: that inner change does not begin in an orderly fashion at an appointed hour and with rational, coherent, decisive action. It does not leave a platform like a train. Instead, like the stranger in Alfred Benjamin’s neighbourhood, even if you have worked out that there is a journey to be made, even if you have an idea of where it is you wish to go, you may not yet be quite ready to set off. But you have – and this is important – commenced the journey. Amid the countless reasons out there in the world for wanting to change, you have identified the universal departure point: autonomy. And in the process, you have begun to change.

Suffice to say, Ed Coxon did not become a special constable and seven or eight more years of fine music-making ensued. In the early 1990s and now in his late twenties, Ed joined an eminent string ensemble, but soon found himself embroiled in an ill-advised love affair with the artistic director. ‘‘Business and pleasure,’’ he says, looking at his feet, ‘‘a very dangerous mix.’’ When the liaison turned sour, Ed was, in his words, ‘‘unceremoniously dumped’’ from both relationship and job. ‘‘It was the first time I’d experienced negative politics in music and I was very off ended, very upset. And that was very much a turning-point.’’

Ed moved into session music and his disillusionment snowballed. There were high points – recording with Pink Floyd, two James Bond soundtracks, a private concert with Paul McCartney – but something had broken. He felt worn out and jaded. The focus and drive of his youth now dwindled to a bitterness that jarred with the yearning that had grown within him to lead a more authentic life, to do something ‘‘real’’.

‘‘This is the point at which I started to think much more seriously, Well, what else is there?’’ Ed says it again, slicing the air on each word. ‘‘Because I just didn’t want to become that embittered person and there was every chance I might.’’

Here then was Revelation Number Two: that if you are not careful, you may turn into somebody you do not wish to be. Within that realisation the seeds of taking control, of active change, were sown. Because, of course, the maelstrom of growing up, long beyond adolescence, does not just bring disillusionment. It also brings independence; it brings choice and the possibility of acting on that choice.

‘‘The mind’’, the philosopher and father of modern psychology William James wrote in 1890, ‘‘is at every stage a theatre of simultaneous possibilities.’’ You choose, according to James, by comparing, selecting or suppressing them with the laser beam of your attention. Perturbed by what remaining a professional musician might do to him as a person, Ed now returned his attention to the possibility of police work.

A full decade on from the first twinge of desire to look beyond the music of his childhood, he began in earnest to picture an entirely different life. Law enforcement seemed more than ever to offer him something he was missing: a way to ‘‘distinguish between right and wrong and good and evil and black and white and up and down and left and right’’. He laughs as he says this, but he clearly still believes it. All the reasons to change, all those simultaneous possibilities, were now there for the choosing. The final impetus to action itself would boil over from a more universal milestone in the maturing process – the death of his father in 2001, when Ed was 35.

‘‘Realising I could never get my dad back’’, he says, ‘‘was the point at which I thought, Well, now I’m the only one who’s responsible for what happens in my life. I saw that change was inevitable and imperative for me, because’’ – he searches for the words – ‘‘well, life is in session. This isn’t a rehearsal.’’ Without delay Ed prepared what he calls, with a grin, ‘‘my renaissance’’. Within months of his father’s death, he had applied to join the Lothian and Borders Police, back in his home city of Edinburgh.

‘‘I remember going over the application meticulously’’, says Ed, smiling broadly, ‘‘and thinking that I had to keep this a secret, because I would be derided by most of my colleagues and I might start to question myself. And I didn’t want to question myself. So I told nobody. Not even my mother.’’

Ed travelled ‘‘totally incognito’’ to Scotland for the first interview. On getting through, he told only his mother and within days his London house was on the market. Finally, in the spring of 2003 and to howls of ‘‘You’re crazy! You’re mad!’’ from colleagues and friends, Edmund Coxon ceased to be a professional musician and from that day on he was a police officer.

‘‘I don’t recall that I got any positive response from anybody’’, he says. ‘‘It was just incredulity. Because the classical music world, it’s inhabited by the privileged and the few, so why would you disembark from that to something that’s not nearly so cosy and well paid? Well, I’ll tell you: just for honesty’s sake. Just because it’s real.’’

Now, as if he has said everything he needed to say, Ed moves to get up, pausing only to add, ‘‘Once I was in the job, I knew I’d done the right thing. I felt totally rejuvenated. It really was a renaissance, a rebirth and I was in control of it.’’ He nods toward the instrument in the dining-room. ‘‘I do occasionally miss playing the violin, but not very often, and yes, before you ask, I do love the police as much as I love music. I think I’m still a musician. I still play tunes on my fingers, but I’m also a police officer.’’ And he smiles and puts on his coat.

Driving to collect Ed’s two-year-old from nursery through Edinburgh’s steep, rain-streaked thoroughfares, you pass suburban bungalows, council estates, elegant Georgian town houses. There are shoppers with their hoods up, the homeless propped in doorways, suited office workers hailing cabs, schoolboys smoking at a bus stop. An old lady peers out from behind a net curtain, a mother tugs down the rain shield on her child’s pushchair, all of them part of the community served by Ed and the officers of the Edinburgh South hub. This, you realise, is what he meant by real life. It makes sense, somehow, of why Ed changed.

Meanwhile, he is talking about the pieces of music that marked particular milestones when he was growing up. There are a few, but he offers one in particular that will, he says, ‘‘remain with me for the rest of my days’’. It is by Richard Strauss and is scored for 23 solo strings. Ed first played it here in Edinburgh as a teenager.

Its name? "Metamorphosen".

Extracted from ‘Metamorphosis; How and Why We Change’ by Polly Morland (Profile, £12.99), to be published on 19 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments