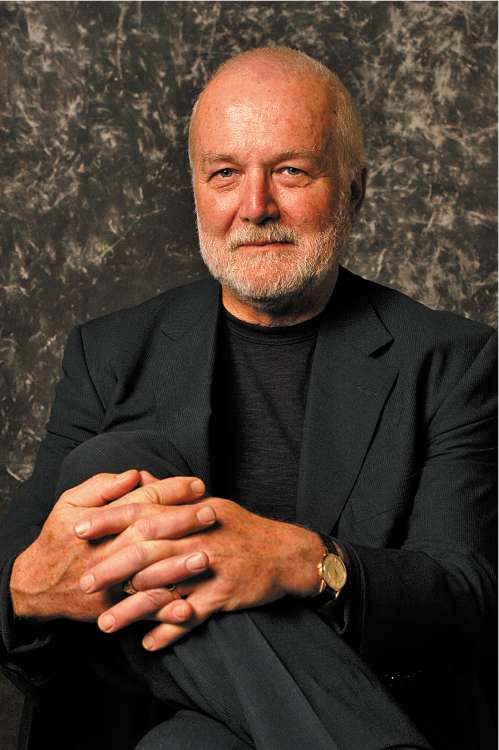

Russell Banks: Class warrior in a club tie

Russell Banks's fiction is as politically engaged as ever, he tells John Freeman – even if he has joined an elite New York club

Spend some time with the American novelist Russell Banks, and the phrase "lived memory" will likely come up. Sitting in a back booth of the Princeton Club in New York City, a throwback to the time when men drank only with men and university ties were worn with pride, the tall, barrel-chested, white-bearded author of Affliction and 10 other novels drops the phrase several times. He is talking about America in the mid-1930s, when highly successful writers like John Dos Passos and Richard Wright were openly radical and an enormous gap between the haves and have nots yawned. "It's a fascinating period," Banks says, blue eyes squinting. "And it's fading from lived memory. I think one of the tasks of a novelist is to try and re-gather and hold on to that lived experience, if possible."

This prerogative is felt throughout The Reserve (Bloomsbury, £14.99), which will be something of a surprise for writers who have followed his career. Set in 1936 on an enormous wilderness reserve in the Adirondack Mountains, populated by the super-wealthy, it unfolds a long way from the gritty, New England hamlets of Banks's well-known Affliction and The Sweet Hereafter. You won't find any of his characters pulling out a tooth with hand pliers, as Wade Whitehouse did in Affliction. They'd probably use much more delicate tools.

Two of the book's primary characters are a well-to-do doctor and his baron-dating child, Vanessa Cole, who is the Paris Hilton of her day. She becomes entangled with Jordan Groves, an artist modelled from Rockwell Kent. In spite of his material success, Jordan remains an outsider. The rich buy his pictures, and he reacts to their patronage by flouting their rules – landing his biplane on their quiet lake, turning up at parties in clothes not unlike those worn by the townies.

Thrusting Jordan and Vanessa together set off a typical wrong-side-of-the-tracks romance, but Banks says he was after something a little more. "I was testing out this idea that an artist could belong to any class," he says. Wearing a multi-coloured scarf in a club like the Princeton, Banks has already signalled where his sympathies lie. "You can go back as far as Mark Twain to see this. An artist who is successful, especially figures of the left who identify with the poor and oppressed, have clientele, a social milieu, and support" from the class whose politics the work attacks.

"Dos Passos is typical, but so today is Tony Kushner, so is EL Doctorow, so am I – anyone who has positioned his politics on the left ends up with that kind of contradiction. The mythology is that's no problem because an artist can belong to any class: but what I believe is that an artist can't belong to any class."

Banks's insertion of himself in this equation downplays what must be a major, ongoing issue. This world is not his by birth. He grew up poor around New England, his father a hard-drinking, difficult man. He was given a scholarship to elite Colgate University in upstate New York, but dropped out after six weeks. "I couldn't deal with it – I was... an affirmative action kid. I was the first in a programme to try and bring in children who weren't the sons of captains of industry." Banks hitched to Florida, hoping to join Castro in the Sierra Maestra, and got "as far as Miami. By then Castro didn't need me, this skinny kid who didn't speak Spanish." The trip was eye-opening, as Banks discovered the segregated south. "It was like walking into South Africa under Apartheid."

Banks landed finally in North Carolina in 1964, where he returned to college – with his first wife and kids – and became involved in Students for a Democratic Society and civil-rights protests. Because he was from the lower classes, being white didn't matter that much.

"Chapel Hill was the most liberal city in the south," he remembers, "but when I drove into town they were integrating the restaurants and bars right then. I walked right into the middle of it, and that politicised me." Banks's early work took him directly back to his New England roots: poetry like Snow (1974), novels like Hamilton Stark (1978) – the tale of a New Hampshire pipe-fitter who evicts his mother from the house she raised him in.

In his own life, however, he was becoming more and more politically engaged with the Caribbean. Eventually he moved to Jamaica for several years, where he got an entirely different perspective of the American empire. "It was a turning point for me, in many ways. Seeing America from a third-world perspective – I got into the whole history of slavery then, since it's such a present fact of Jamaican life." Out of this period came The Book of Jamaica (1980), but also Banks's tremendous breakthrough novel, Continental Drift (1985), which was published shortly after he began teaching at Princeton University. Our meeting choice is "a residual of my years there," he says, laughing, shooing away my wallet. "You can't pay, it's a club."

The success of Banks's next novels and their later film adaptation has catapulted him even further from his roots. He has worked closely with some of Hollywood's best actors and directors as his books have been adapted to screen, from Affliction, in which James Coburn won an Academy Award, to The Sweet Hereafter. He is now collaborating with Martin Scorsese on adaptations of his two latest novels, Cloudsplitter (1998) and The Darling (2004).

He has a house in Miami Beach, another near Saratoga Springs, and belongs to The Ausable Club, a reserve not unlike the one in the book. "My wife's family had belonged to it for generations," he explains, referring to his fourth wife, the poet Chase Twitchell. "I didn't want to join for years – but they own 15,000 acres of the most beautiful pristine wilderness this side of the Rockies, and they have a terrific clubhouse with a great restaurant and a bar, complete with an Irishman who can make great martinis."

Rather than skirt these contradictions in his life, Banks has written straight into the heart of them. Land is at the heart of The Reserve – something he is keen to explain. "All across the country, upper middle-class and upper-class people are coming in, buying up vast tracks of land, to preserve it, but basically crippling the economy of locals". Banks's face pains. "It's a double-edge sword."

Banks is unapologetic about these contemporary echoes in The Reserve and says they are, for him, the point of writing historical fiction. "There's no point writing about historical fiction unless it has something to do with the present," he says: "otherwise it's just escapism. I don't have anything against escapism or entertainment, but I have no interest in writing it. Here we are in the middle of a mortgage foreclosure crisis, and the biggest gap between the rich and the poor that's existed since the 1930s, and nobody is noticing the parallels."

Banks's great care at reviving the spirit of the day in The Reserve softens the book's political edge. But a keen eye will spot the signifiers. Among the writers who appears in it is Dos Passos, who has fallen from fashion in the US. "Part of it has to do with his radical politics," Banks speculates. "Those books are really much about class, but that is a subject that in our era is almost taboo. As somebody starts talking about poverty, somebody else starts pointing a finger and saying, class war, class war... The sensitivity to any discussion of class in this country is phenomenal."

Banks sees a clear reason why Americans steer clear of the issue. "There's an inherent conflict at the heart of the so-called American Dream – on one hand – and the long-standing social reality of class in America," he says. "We need to deny that reality in order to believe in the American Dream, and yet nonetheless, still today, 90 per cent of people born in poverty remain in poverty... 90 percent of people born to wealth stay wealthy." Clearly, Banks knows he is an exception. But he's also keen not to forget other advantages, which are impossible to be disinherited from. "Here we are, white males in what is essentially a racist and misogynist society," he says, looking at me, not long before one of his four daughters comes to take him back to the world he belongs to – sort of.

John Freeman is writing a book on the tyranny of email for Scribner

Biography

Russell Banks

Russell Banks was born in 1940 in Newton, Massachusetts, and grew up in relative poverty in New England. He was awarded a scholarship to Colgate University, New York, but dropped out after six weeks and hitched south. He started writing when living in Miami in the late 1950s, and later moved to Jamaica and North Carolina before returning north to teach at Princeton University. His books include the poetry collection Snow (1974), short story collections such as The Angel on the Roof (2000) and 11 novels. Affliction (1989) and The Sweet Hereafter (1991) have been made into films, with two more under way. The Reserve is published by Bloomsbury. He is an artist-in-residence at the University of Maryland and lives in upstate New York with his fourth wife, the poet Chase Twitchell.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments